The Stupidest Animal on the Farm.

The Fourth Sunday of Easter.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Acts 13: 14, 43-52.

• Psalm 100: 1-3, 5.

• Revelation 7: 9, 14-17.

• John 10: 27-30.

The Third Sunday after Easter.*

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Peter 2: 11-19.

• [The Gradual is omitted.]

• John 16: 16-22.

The Sunday of the Paralytic; the Feast of Our Venerable Father Simeon of Persia; and, the Feast of the Venerable Acacius, Bishop of Melitene.

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Acts 9: 32-42.

• John 5: 1-15.

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:30 AM 4/17/2016 — The Gospel lessons of all three of the annual cycles of Scripture lessons for this Sunday are all different portions of the same long narrative in which our expounds upon Himself using the image of the Good Shepherd, and there are few images of our Lord more pleasing to us than that. Our Lord's own words, as related to us by the Blessed Apostle John, betray why: the good shepherd is the one who lays down his life for his sheep; but, I've often wondered what our Lord's disciples were thinking when they heard Him utter those familiar words. After all, we're accustomed to regarding our Lord's verbal images metaphorically; we have to because none of us here are actually making a living herding sheep, but our Lord used the metaphor because there were some hearing Him preach who actually did make their living that way, and they had to be somewhat puzzled. After all, a shepherd is a business man: he maintains a flock of sheep because he's in the business of producing wool; the sheep in his flock are products, not objects of love, and he's not going to give his life for them. 8:30 AM 4/17/2016 — The Gospel lessons of all three of the annual cycles of Scripture lessons for this Sunday are all different portions of the same long narrative in which our expounds upon Himself using the image of the Good Shepherd, and there are few images of our Lord more pleasing to us than that. Our Lord's own words, as related to us by the Blessed Apostle John, betray why: the good shepherd is the one who lays down his life for his sheep; but, I've often wondered what our Lord's disciples were thinking when they heard Him utter those familiar words. After all, we're accustomed to regarding our Lord's verbal images metaphorically; we have to because none of us here are actually making a living herding sheep, but our Lord used the metaphor because there were some hearing Him preach who actually did make their living that way, and they had to be somewhat puzzled. After all, a shepherd is a business man: he maintains a flock of sheep because he's in the business of producing wool; the sheep in his flock are products, not objects of love, and he's not going to give his life for them.

Our Lord expressed it somewhat differently: He makes the distinction, in the few verses leading up to today's Gospel lesson, between the shepherd who is hired to do the job and the shepherd to whom the flock actually belongs. The hired shepherd, who is the employee of someone else, isn't going to sacrifice himself when the wolf comes prowling; but, the shepherd who actually owns the sheep would naturally be a bit more concerned since it's his livelihood that the wolf is threatening.

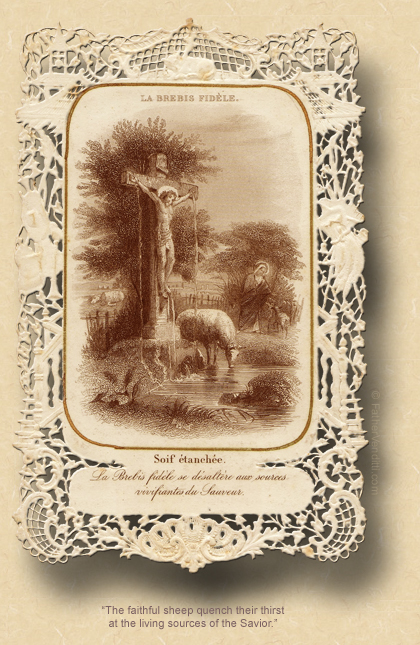

All of these analogies are limping to us because, as I said, none of us are shepherds. That doesn't stop us, of course, from recognizing the beauty of our Lord's mental image; and, the image of the Good Shepherd who lays down his life for his sheep remains one of our favorites, as it was for the Fathers of the Church, and the image of the Good Shepherd has become engrained in the language of the Church: whenever we speak of our Holy Father, the Pope, or of the office of the bishop or the role of the parish priest, the metaphor of the Good Shepherd naturally comes to our lips; and, we speak of the priest shepherding his flock without even thinking about it, so powerful is the image the Lord has given us with His words.

I have a classmate from the seminary who is now the bishop of a diocese out west; and, in our day they didn't give you a summer assignment in a parish like they do now days; you actually had to go out and get a job for the summer; and one year he got himself a summer job working as a shepherd. A couple of years after we were ordained we had the opportunity to take a vacation together—it was actually a group of five of us who had been in the seminary together but who were now scattered around the country in different assignments, since we all belonged to different dioceses—and we decided to take three weeks and go on pilgrimage together to different holy sites in Europe.  And we went to a lot of different places, mostly in France: we went to Lourdes, of course; we went to Ars to pray at the tomb of St. John Vianney, patron saint of parish priests; we went to the Visitation convent in Paray-le-Monial where Saint Margaret Mary received her visions of the Sacred Heart; we went to Lisieux to pray to the Little Flower; we visited all kinds of places. And one of the places we visited was the Basilica of Our Lady of La Salette, high up in the French Alps, a little off the beaten track, which was the site of an apparition of the Mother of God to two children in 1846, and which was approved by the Church just a few years later in 1852. It's not a popular pilgrimage destination like Lourdes and Fatima primarily because it's almost impossible to get to: there's only one road up that mountain, and it's impassible in the winter; and, we had rented this crummy Citron van from some crook in Paris which had no air conditioning—and this was in the middle of August—and could hardly go more than thirty miles per hour, and we decided to try and drive up there. And on the way there we drove through some very picturesque countryside where there are a lot of farms, many of them raising sheep. And more than once, as we were driving along, we'd pass by some field where sheep were grazing, and one sheep would decide, just as we were approaching, to cross the road in front of us; and, when one sheep decides the cross the road, they all have to cross the road. And there's nothing you can do about it: you can blow your horn all you want, it's not going to stop them; so, several times during that drive we had to stop and just watch a herd of sheep as they crossed the road in front of our van. And on one occasion, I was driving, and my classmate, who had worked as a shepherd, was riding shotgun next to me, and we were sitting there watching these sheep go by in front of us, and he looked at me and said, “You know, sheep are really stupid.” And it's true; if you ever meet someone who's had anything to do with raising sheep, they'll tell you the same thing: they are the dumbest animals on the farm. And we went to a lot of different places, mostly in France: we went to Lourdes, of course; we went to Ars to pray at the tomb of St. John Vianney, patron saint of parish priests; we went to the Visitation convent in Paray-le-Monial where Saint Margaret Mary received her visions of the Sacred Heart; we went to Lisieux to pray to the Little Flower; we visited all kinds of places. And one of the places we visited was the Basilica of Our Lady of La Salette, high up in the French Alps, a little off the beaten track, which was the site of an apparition of the Mother of God to two children in 1846, and which was approved by the Church just a few years later in 1852. It's not a popular pilgrimage destination like Lourdes and Fatima primarily because it's almost impossible to get to: there's only one road up that mountain, and it's impassible in the winter; and, we had rented this crummy Citron van from some crook in Paris which had no air conditioning—and this was in the middle of August—and could hardly go more than thirty miles per hour, and we decided to try and drive up there. And on the way there we drove through some very picturesque countryside where there are a lot of farms, many of them raising sheep. And more than once, as we were driving along, we'd pass by some field where sheep were grazing, and one sheep would decide, just as we were approaching, to cross the road in front of us; and, when one sheep decides the cross the road, they all have to cross the road. And there's nothing you can do about it: you can blow your horn all you want, it's not going to stop them; so, several times during that drive we had to stop and just watch a herd of sheep as they crossed the road in front of our van. And on one occasion, I was driving, and my classmate, who had worked as a shepherd, was riding shotgun next to me, and we were sitting there watching these sheep go by in front of us, and he looked at me and said, “You know, sheep are really stupid.” And it's true; if you ever meet someone who's had anything to do with raising sheep, they'll tell you the same thing: they are the dumbest animals on the farm.

Which causes me to question whether the imagery used by our Lord in describing Himself as the Good Shepherd and us as His sheep might contain a hint of a rebuke. After all, there are other images used by our Lord in the Gospels that are a bit more flattering: a father and his children, a general and his soldiers; they all make the same point; but, a shepherd and his sheep? Who wants to be regarded as a sheep?

The answer is, we do. We want to be our Lord's sheep because, as our Lord says, the Good Shepherd lays down his life for his sheep. Penetrating deep into that image, we realize that the Good Shepherd puts Himself willingly between the wolf and His sheep for no practical reason, and without any hope of receiving anything in return. He does it because He knows that the sheep, being the stupidest animals on the farm, have absolutely no facility to protect themselves.  And while we often use the Gospel of the Good Shepherd to expound on the qualities of what makes a good shepherd, using it to talk about priests and bishops and what they should be, it behooves us, I think, to consider what it is that makes a good sheep; and, what makes a good sheep is complete obedience and docility to the will of the Shepherd. The Shepherd is able to protect His sheep and keep them safe only when the sheep go where the Shepherd tells them to go. It's when the sheep decide to go off on their own and wander that the Shepherd loses sight of them and is no longer able to protect them. And while we often use the Gospel of the Good Shepherd to expound on the qualities of what makes a good shepherd, using it to talk about priests and bishops and what they should be, it behooves us, I think, to consider what it is that makes a good sheep; and, what makes a good sheep is complete obedience and docility to the will of the Shepherd. The Shepherd is able to protect His sheep and keep them safe only when the sheep go where the Shepherd tells them to go. It's when the sheep decide to go off on their own and wander that the Shepherd loses sight of them and is no longer able to protect them.

All last week, in the Apostolic lessons for the Masses during the week, we were presented the account, from the Acts of the Apostles, in which the first seven deacons of the Church were selected, and how the Apostles made that decision because they needed people to assume the more pragmatic tasks in the Church so that they would remain free to celebrate the Sacred Mysteries and concentrate on the preaching of the word; and, from that I attempted to guide those who attend Holy Mass here daily to the conclusion that we need to allow our priests to be priests, and stop trying to make them be what they are not. One of the examples we looked at together is what often happens in the confessional, where someone comes in and starts telling the priest all about his or her problems as if the priest is some kind of counselor or religious therapist who doesn't charge anything, and how that is not his job; his job is to hear our sins on behalf of our Lord, and give us our Lord's absolution, and all he needs to know to do that is what we did and that we're sorry; he certainly doesn't need to know what's bothering us, nor is he specifically trained to help us with our personal problems. That being said, people do often expect priests to help them sort out their lives, but often don't make the connection between all the bad stuff that's going on in their lives and the fact that they've made little or no effort to live a Christian life. Some people simply don't make the connection between the fact that their lives are falling apart and the fact that they don't go to Mass on Sundays or that they're shacked up with someone outside of marriage or whatever. Now, our Lord did say that the Good Shepherd will often leave the flock to go and search for the one lost sheep that's gone astray (cf. Luke 15: 4ff), and that's true; but, the lost sheep has to want to be found.

So, on this Sunday on which the Lord presents to us the image of the Good Shepherd, we should remember to pray for our Holy Father, the Pope, for our Bishop and for the priests that he has appointed to guide us in the ways of grace, and beg the Lord to help them be the best shepherds they can be. But we should also consider that we must do our part, for the good shepherd is only as good as the flock he tends; and, if we want our shepherds to be good shepherds, like our Blessed Lord, then we must resolve to be good sheep.

* In the Missal of St. John XXIII, the Third Sunday after Easter means the third after the Octave, in effect the fourth of the Easter Season.

|