It Is Impossible for Us Not to Speak of What We Have Seen and Heard.

Easter Satuday.

Lessons from the feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Acts 4: 13-21.

• Psalm 118: 1, 14-21.

• Mark 16: 9-15.

Lessons from the feria, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Peter 2: 1-10.

• [see note below.]*

• John 20: 1-9.

Bright Saturday.

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the typicon of the Byzantine-Ruthenian Rite:

• Acts. 3: 11-16.

• John 3: 22-33.

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:27 AM 4/11/2015 — As you know, we have something of a busy weekend here at the Shrine, so today's homily should be a brief one … emphasis on the word “should.” And we begin by recapping what we have been looking at during this Octave of Easter.

So far, we've reflected on the three appearances of our Risen Lord on the three days I was able to preach to you: our Lord's encounter with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, His appearance to the apostles in Jerusalem, both of those being from Luke, and yesterday's early morning breakfast with the apostles by the Sea of Tiberias where they all first met three years before. And we pulled a lot of interesting points out of them: the fact that the two disciples in Emmaus were not priests, so they couldn't recognize our Lord until He offered Holy Mass for them and gave them Holy Communion; the apostles were priests, so they recognized him right off the bat, and had no need for Him to offer the Eucharist, since they were able to do this on their own; and we kind of made fun of them during their class reunion, as it were, on the beach by the sea; and, we were able, I hope, to make some salient points in each case.

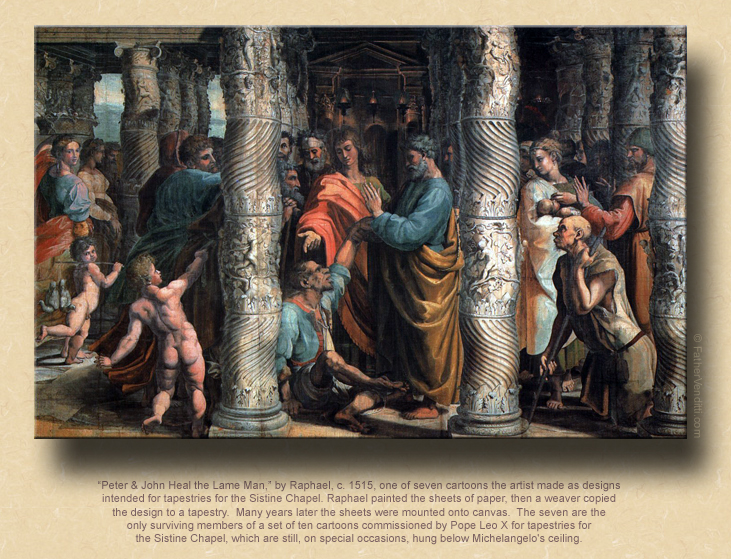

Now, during this time, an entirely different narrative has been taking place during the Octave in the Apostolic lessons from the Acts of the Apostles, which we haven't been discussing, beginning on Wednesday with the cure of a cripple by Peter and John, with the following day's lessons devoted to Peter's speech after the pair are arrested for doing it....

Those lessons were presented because they represent a very early—the earliest, in fact—theological exposition on the nature of our Lord's bodily resurrection. Both narratives wrap up in the lessons of today's Mass, and the whole beautiful presentation of our Lord's glorious resurrection is brought to completion tomorrow with the well-known appearance of our Lord in the upper room, and the proof of His resurrection to Thomas.

My thoughts on the apostle Thomas are unique to say the least; but, because it is also Divine Mercy Sunday, I don't know how many of you will be here to hear them; but, we will make the effort anyway at our usual noon Mass before our Divine Mercy activities begin. What Father Ronan will preach about at the big Mass tomorrow I have no idea.

One of the points I hope you have noticed—in addition to the esoteric one's we been reflecting on—is that almost all of the post-resurrection appearances of our Lord end with some form of apostolic mandate. To Mary Magdalene, the first to see Him risen, Jesus says, “Return to my brethren, and tell them this; I am going up to him who is my Father and your Father, who is my God and your God.” (John 20: 17 Knox). To the other women who were the next to meet Him, he says, “Do not be afraid; go and give word to my brethren to remove into Galilee; they shall see me there” (Matt. 28: 10 Knox). The two disciples at Emmaus aren't given a command in words, but were certainly moved that very night to run to the apostles and tell them what had happened (cf. Luke 24: 35). The only post-resurrection appearance of our Lord that doesn't include an apostolic mandate is the one on the beach we read of yesterday, where the only thing our Lord commands the apostles to do is have breakfast.

Today's Gospel lesson, of course, is the summation, in which is contained the great apostolic mandate which will continue in force for all time: “And he said to them, 'Go out all over the world and preach the gospel to the whole of creation; he who believes and is baptized will be saved; he who refuses belief will be condemned'” (Mark 16: 15-16 Knox). And from that moment on, the apostles began to bear testimony to that which they had seen and heard, and preached repentance and the forgiveness of sins in His name to all the nations, beginning in Jerusalem (cf. Luke 24: 44-47).

Take note of the fact that, not long after this, in the very beginning of the Acts of the Apostles, when the time comes to pick a replacement for Judas, one of the conditions is that the candidate be someone who was a personal witness to the resurrection (1: 21-22), and that's because it is a firm belief in the resurrection—in the truth of the faith—that gives any and every apostolic endeavor its fuel. In today's lesson from Acts 4, the members of the Sanhedrin who had arrested Peter and John following the cure of the cripple weren't of a malicious mind; they wanted to let them go; all they required in exchange for their freedom was that they stop preaching the resurrection of our Lord which was, for obvious reasons, so upsetting to those who had been complicit in our Lord's death; in other words, they had to stop preaching the truth. The apostles' reply, of course, is boilerplate—“Are we supposed to obey you or God?” (cf. 4: 19)—that is, until Peter adds the line, “It is impossible for us to refrain from speaking of what we have seen and heard” (v. 20 Knox).

In other words, their preaching is not based on intellectual conviction—the scribes themselves remarked on the fact that they were “uneducated, ordinary men”—nor is it based on some emotional experience. Their preaching is based, quite simply, on the fact that they saw our Lord alive! Tomorrow, we will hear our Lord tell Thomas, “Blessed are those who have not seen and have believed” (John 20: 29 NABRE), and we accept that because our Lord said it; but on the other hand, if you've actually seen it, case closed! There's just nothing further to discus.

Beginning with the Apostle James, all of the apostles, save one, would end up dying a martyr's death. Comparatively speaking, it was easy for them to make that choice; the truth they were dying for was not something they read in a Bible, or learned in a seminary somewhere, or embraced in the emotion of the moment after hearing a particularly dynamic speaker or attending some sort of over-emotionalized retreat experience. They could die for the truth because they had actually seen the truth; it was as plain to them as the noses on their faces.  In this sense, the martyrs which followed them, from sub-apostolic times to the present, had a much tougher choice to make, because they weren't yet born when our Lord rose, and didn't see it first hand. And yet, the truth was still just as clear to them as it was to the apostles, or else they wouldn't have died like they did. And lest you think this is just a history lesson, may I remind you that this is happening right now. All over the world, but particularly in the Middle East, Christians are being slaughtered hundreds at a time simply because they refuse to renounce the truth: people of our own time, to whom the truth of the faith is as clear as it would be if they had actually been there in the upper room and seen our Lord themselves. There has not been such a mass, global war against Christ and His Church since the days of Nero. In this sense, the martyrs which followed them, from sub-apostolic times to the present, had a much tougher choice to make, because they weren't yet born when our Lord rose, and didn't see it first hand. And yet, the truth was still just as clear to them as it was to the apostles, or else they wouldn't have died like they did. And lest you think this is just a history lesson, may I remind you that this is happening right now. All over the world, but particularly in the Middle East, Christians are being slaughtered hundreds at a time simply because they refuse to renounce the truth: people of our own time, to whom the truth of the faith is as clear as it would be if they had actually been there in the upper room and seen our Lord themselves. There has not been such a mass, global war against Christ and His Church since the days of Nero.

Now, we could ask ourselves the obvious disturbing question: if some hooded monster with a gun came up to any one of us and gave us the choice to renounce our Lord or die, what choice would we make? In any other time in history it would be a purely academic question, but not anymore. But, rather than do that, I would pose to you another question: how is it possible that, at this very moment in history, when we are witnesses to martyrdom the likes of which the Church has not seen since the Roman Circus, some leaders in our own Church can question basic dogmas of the faith regarding marriage, and the absolute necessity of being in the state of Grace to worthily receive Holy Communion, thus rejecting our Blessed Lord's command to "Feed my sheep" (John 21: 17)? How can we reconcile a mother and her children allowing themselves to be gunned down, beheaded or burned alive because they won't deny our Lord, while in some other country an important Catholic churchman can proclaim, with all sincerity, that no one should be excluded from Communion because, after all, the Eucharist is really just a symbol of fellowship? The answer, of course, is simple. It was given by Peter and John in today's first lesson:

So they called them in, and warned them not to utter a word or give any teaching in the name of Jesus. At this, Peter and John answered them, “Judge for yourselves whether it would be right for us, in the sight of God, to listen to your voice instead of God’s. It is impossible for us to refrain from speaking of what we have seen and heard” (Acts 4: 18-20 Knox).

And when someone does refrain from speaking of it—even to the point of castigating those who do—it can only be because that person no longer sees and hears; he no longer believes; and all of his protestations about kindness and mercy and inclusion and what he calls charity ring very hollow, especially in the face of those who have died—and are now dying—for the truth of what they so clearly still see and hear. They are not cardinals and bishops, they are not theologians or even popes. They are exactly what the Sanhedrin observed about Peter and John: “uneducated, ordinary men” (v. 13), but men who had seen and heard and, therefore, believed.

It remains for us, who are neither threatened with martyrdom—at least not in the flesh, though we do have our own little struggles every day—nor being asked to decide the great issues of the Church in our day, to continue to challenge ourselves to always remember that, while we may be separated from our Lord's apostles by many centuries, we still hear Him every day in his word, and see Him every day in His Most Blessed Sacrament. Should not, then, the truth of the faith be just as clear to us now as it was to them?

* In the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, from this day until the end of Eastertide, the Gradual Psalm is omitted.

|