Time, Once Again, for More "First Friday Footnote Frenzy."

The Fourth Friday of Lent; and, the Commemoration of Saint Casimir.*

Lessons from the alternate feria,** according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Exodus 17: 1-7.

• Psalm 95: 1-2, 6-9.

• John 4: 5-42.

|

When the lessons from the current feria are taken:

• Hosea 14: 2-10.

• Psalm 81: 6-11, 14-17.

• Mark 12: 28-34.

|

The Fourth Friday of Lent; the Commemoration of Saint Casimir, Confessor; and, the Commemoration of Saint Lucius I, Pope & Martyr.***

Lessons from the feria, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Numbers 20: 1-3, 6-13.

• Psalm 27: 7, 1.

• Psalm 102: 10.

• John 4: 5-42.

The Fourth Friday of the Great Fast; and, the Feast of Our Venerable Father Gerasimus of the Jordan.

Lessons for the Presanctified,† according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Genesis 12: 1-7.

• Proverbs 14: 15-26.

FatherVenditti.com

|

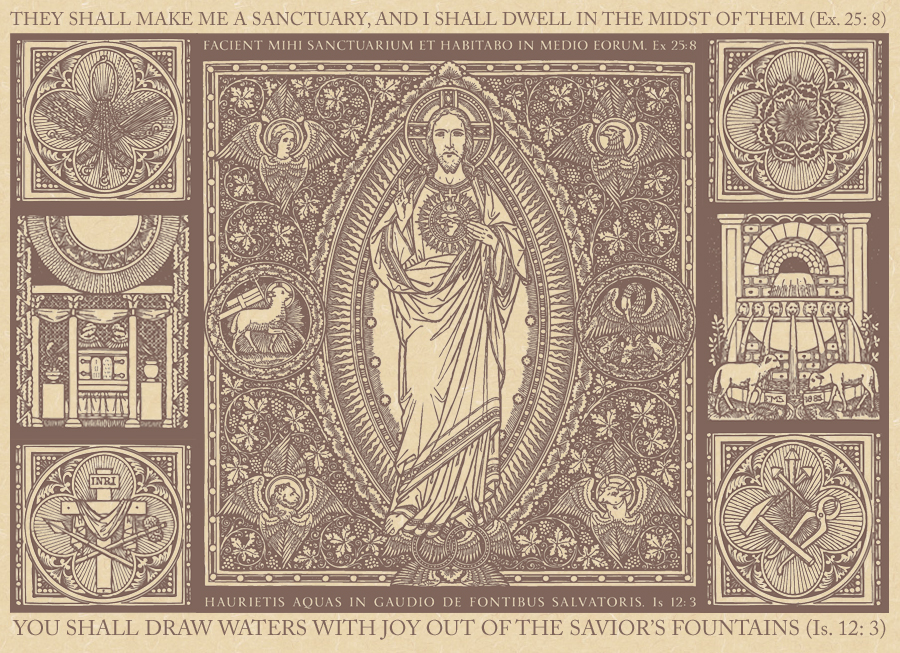

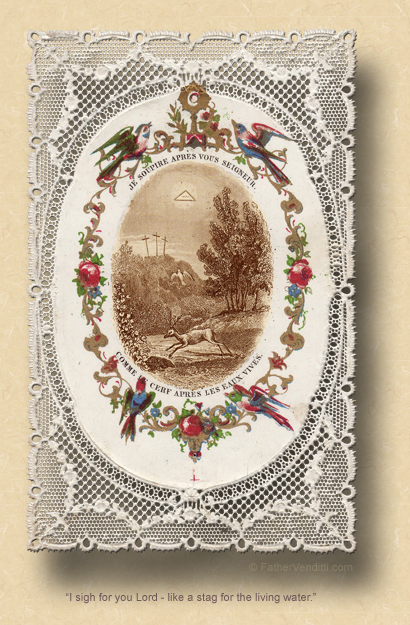

10:02 AM 3/4/2016 — The First Friday of the Month, of course, means that we'll expose the Blessed Sacrament after Holy Communion today in honor of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, and a Friday in Lent means the Stations of the Cross, which we will pray in the presence of our Eucharistic Lord, even though the Mass today must be for the Lenten feria. If you're confused about the Scripture lessons we just heard, that's because we're taking them today from the alternate lessons offered by the Roman Missal for use any day this week at the discretion of the priest. 10:02 AM 3/4/2016 — The First Friday of the Month, of course, means that we'll expose the Blessed Sacrament after Holy Communion today in honor of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, and a Friday in Lent means the Stations of the Cross, which we will pray in the presence of our Eucharistic Lord, even though the Mass today must be for the Lenten feria. If you're confused about the Scripture lessons we just heard, that's because we're taking them today from the alternate lessons offered by the Roman Missal for use any day this week at the discretion of the priest.

Last Sunday we heard the Parable of the Fig Tree but, if I had wanted to, the Roman Missal would have allowed me to read to you the Gospel of the Samaritan Woman, as it's so integral to this holy season. I chose not to do that, which means the story of her encounter with our Lord at Jacob's Well is made available as an alternate lesson which may be read on any day this week, and I've chosen to read it today. The Missal does this because the passage is so rich in meaning and so full of hidden innuendos that it’s no wonder the Fathers of the Church never seem to tire of talking about it. It has everything in it, if you only know where to look: it has religion, it has politics, it has morality, it has history. We can’t touch on all or even half of what this passage means. But we can say a few things, and they require us to know something about the place and the time.

Samaria was part of the old "Upper Kingdom" of Israel—some Bibles have maps in them showing how things were in Biblical times, and if there are any included in the Old Testament, you'll find one that shows what it calls the “Upper Kingdom” and the “Lower Kingdom.” The original twelve tribes of Israel suffered a kind of civil war, with the largest and most powerful of them, the tribe of Judah, separating from the rest and moving south, and building a capitol at the old village of Jerusalem. The remaining tribes stayed in the North; they had no capitol, they had no government; they called themselves the kingdom of Israel, but had no unity, and it wasn’t too long before they were conquered—by the Syrians, by the Babylonians, by all kinds of people—the result being that their religion and culture became polluted. They considered themselves Jews, but the Judeans did not recognize them as such. The Judeans had built a Temple in Jerusalem, but they wouldn’t let the Israelites of the old upper kingdom go there; so they built their own temple on the mountain of Gerizim, near the ancient city of Sychar, in the region known as Samaria; and, before too long, they started referring to themselves as Samaritans, at which point the Judeans co-opted the title of Israelite for themselves alone. And while the Samaritans never stopped thinking of themselves as true Jews, the Judeans regarded them as little more than pious pagans. Remember that Jesus, Himself, in Matthew’s Gospel, when He first sends the disciples out to preach, tells them not to preach to the Samaritans.

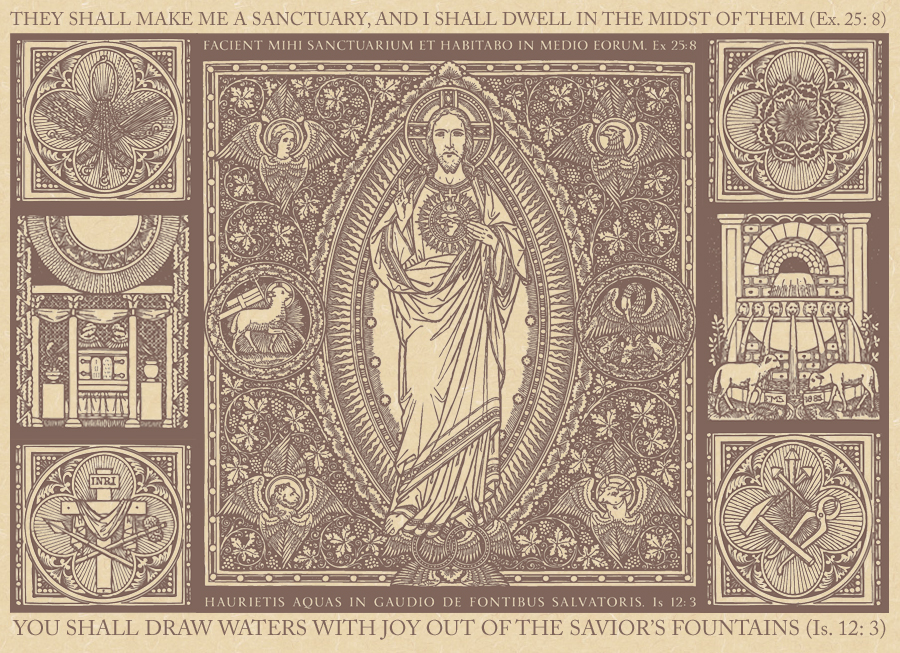

How He ends up in Samaria is not entirely clear. It may have been nothing more than the fact that passing through Samaria was the quickest path for them to get to Jerusalem from where they were. In any case, they end up stopping at a very holy place to the Samaritans—and to the Jews as well—near the city of Sychar. It was a plot of land that Jacob had given to his son, the patriarch Joseph, whose exploits we can read about in the Book of Genesis. Jacob had dug a well there with his own hands. Jesus sends the disciples into town to buy some food, and is sitting on the wall of the well when this woman comes by to get some water. We don’t know why He’s interested in her, especially since He’s already told his own disciples not to the bother with the Samaritans; but, for some reason He’s interested, and He asks her for some water.  He can already see that she is steeped in sin. How? Simple. He’s God. He can see everything. And you can almost hear in her words the political and religious animosity that existed at the time between the Jews and the Samaritans. She wants to know what He’s doing there, and why she should bother herself to draw water from the holy well of Jacob to give a drink to a Jew. It’s the very first instance of anti-Semitism in the Gospel. He can already see that she is steeped in sin. How? Simple. He’s God. He can see everything. And you can almost hear in her words the political and religious animosity that existed at the time between the Jews and the Samaritans. She wants to know what He’s doing there, and why she should bother herself to draw water from the holy well of Jacob to give a drink to a Jew. It’s the very first instance of anti-Semitism in the Gospel.

But Jesus is not about to be distracted from what really interests Him here, which is the state of her wretched soul. He asks to see her husband, knowing full well that, not only has she married and subsequently dumped five husbands, but is now living with someone to whom she isn’t married. She’s been a busy girl. Jesus exposes all this right to her face; and, when she realizes this, she tires to derail Him by engaging Him in a theological debate about temple worship. And she starts talking about how the Jews have their temple in Jerusalem and the Samaritans have theirs on Mt. Gerizim, blah, blah, blah, as if to say, “OK, holy man, let’s see how much you really know.” But Jesus doesn’t fall for it. He’s seen this before. He’s seen this kind of behavior in the Pharisees: always nit-picking about theological details while their souls are blackened with sin. Now, here’s this woman, thinking that she’s so clever engaging our Lord in a discussion of liturgical minutiae, without making an attempt to even pretend to live a good, decent, moral life. Of course, our Lord doesn’t buy this, and when she asks Him directly in which temple is the right one to worship, He’s had enough. And He tells her that it’s not a question of where one worships—Jerusalem or Gerizim or Disneyland, it doesn’t matter—what’s important is that you worship in spirit and in truth. And I can almost picture our Lord pointing His finger right at her face when He says the word “truth,” as if to say, “Look into yourself, honey, because you’re not worthy to worship God anywhere.”

Finally, this woman realizes that she’s being lectured to, and she doesn’t like it. So, she lashes out at him with this line about the Messiah: “…we know that he is coming, and when he does he will reveal all things….” Unfortunately, our English translation doesn't transmit the sarcasm of her words. What she’s really saying to Him is, “Who do you think you are? The Messiah?” And He looks at her and says, “Yes!” And the only reason she doesn’t burst out laughing is because she knows it’s true, otherwise how would He have known about the revolving door into her bedroom? And here, at this point, is where her conversion begins. He slaps her hard: He exposes before her own eyes the ugliness of her sins, and it makes her very angry. Guilty people are like that. They spend 80% of their energy trying to convince everyone how innocent they are, and the remaining 20% trying to convince themselves. And when someone doesn’t let them get away with it, they get angry. She’s angry. But she gets over it. She has to, because our Lord doesn’t leave her any escape. And once she gets over it she begins to realize that it’s time to make some changes in her life.

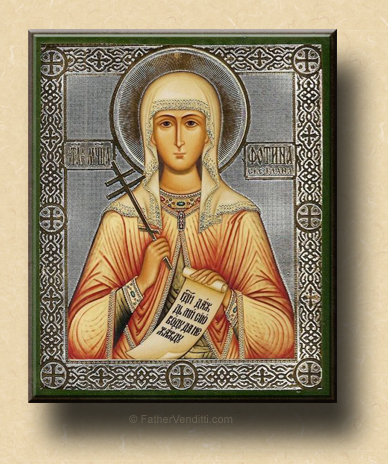

Now, we don’t know what happened to the Samaritan woman. Some of the Eastern Churches give her a name—the Greeks call her Photina, the Russians call her Svetlana or Kyriaka—and have a feast dedicated to her on their calendar, augmented by pious legends about her and her children and how they went on to convert thousands of people and were ultimately martyred by the Emperor Nero, but we don’t really know for sure.†† We would like to think that her conversion was complete and that she became a disciple of Jesus, but we don’t know that. We do know—because we just read it in the Gospel—that she went and told others about Him, and that some of them did become disciples, and that’s a good sign; so, either wittingly or unwittingly, she became an evangelist. And this is where that rather awkward middle section of this Gospel lesson comes into play: when the Apostles return from their shopping trip in town, they offer our Lord something to eat, and he refuses saying that his food is to do the will of his Father.  What’s the will of his Father? To teach all the nations. They don’t understand what he’s talking about, so he gives them this beautiful speech about how they will reap the bounties of what they did not sow, and gather a harvest they did not plant. They couldn’t have planted it because they didn’t die on the cross and rise from the dead, but they will, as the first bishops of the Church, gather the harvest of the countless souls who will be baptized and saved as a result. What’s the will of his Father? To teach all the nations. They don’t understand what he’s talking about, so he gives them this beautiful speech about how they will reap the bounties of what they did not sow, and gather a harvest they did not plant. They couldn’t have planted it because they didn’t die on the cross and rise from the dead, but they will, as the first bishops of the Church, gather the harvest of the countless souls who will be baptized and saved as a result.

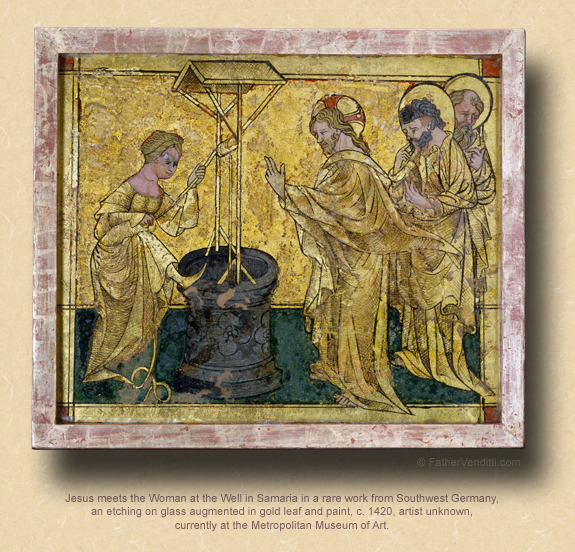

But the important question for us is not what happened ultimately to this woman, but what’s happening to us. We’re not likely to meet Jesus sitting next to a water fountain. But we do meet Him every day in the Scriptures, in the Sacraments, in our own daily prayers. Today we will pray using Saint Josemaría's meditations on the Stations, so maybe He will speak to us through them. He may not confront us as forcefully as He confronted the Samaritan woman; His confrontation of us is much more subtle: sometimes it’s through a sermon, or something we read, or through the example of another, or maybe just some little pang of guilt that we try to dismiss but can’t. But whatever it is, we shouldn’t easily dismiss it. It may just be our Lord trying to make a point.

* Today is what the Roman Missals call "Friday of the Third Week of Lent." Cf. the post here for an explanation of how the days of Lent are identified on this site.

Saint Casimir (1458-1484) was the son of King Casimir IV and Queen Elizabeth, monarchs of Poland and Lithuania. In contrast to other members of the royal court, he was an example of faith, piety, humility and charity to the poor. He had a great love for the Blessed Eucharist and the Blessed Virgin Mary, and is the patron saint of both Poland and Lithuania.

** Because of its importance in the schema of the Church's Lenten observance, the Gospel of the Samaritan Woman, assigned to the lessons of last Sunday according to the primary dominica, may replace the lessons of the other dominical cycles if so desired; however, if the lessons from the current dominical cycle were taken on Sunday—as was the case here—then the Gospel of the Samaritan Woman becomes part of an alternate set of lessons which may be taken, at the discretion of the priest, on any other day this week, so that this important Gospel lesson need not be omitted altogether. The lesson from Exodus is also taken from that same dominical cycle; the psalm is not. Because today is the first Friday of the month, and because the chapel will be full for our Holy Hour and Stations of the Cross, I have chosen to preach on these alternate lessons today; note also that this Gospel lesson is assigned to today in the extraordinary form, making its use today in the ordinary form doubly appropriate.

*** Ordinarily a Feast of the Third Class in the extraordinary form, Saint Casimir's day becomes a commemoration during Lent; the observance of Pope Saint Lucius is always a commemoration. A Mass for neither is available due to the precedence of the Lenten feria.

† In the Byzantine Tradition—as in most Eastern Christian traditions, both Orthodox and Catholic—the Eucharist is not celebrated on the weekdays of the Great Fast. In some traditions, the faithful are expected to fast from the Blessed Eucharist during this time, abstaining from Holy Communion except on Saturdays and Sundays.

In other traditions, including the Ruthenian recension, Holy Communion may be distributed to the faithful daily provided that the Divine Liturgy is not celebrated. On Wednesday and Friday evenings, the Divine Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts is celebrated, consisting of a form of Solemn Vespers coupled with a Communion Service in which the Eucharist confected on the previous Sunday may be received by the faithful. On the other weekdays, another service—usually the Sixth Hour of the Divine Office or a simpler service called "Typica"—may be celebrated at which Holy Communion may also be offered to the faithful. Notice that the readings for these services do not include a Gospel lesson; a Gospel would only be sung on significant Holy Days or during the Presanctified Liturgies of Holy and Great Week.

In response to an inquiry: since, in the Byzantine Tradition, Holy Communion is distributed in both species, with the particles of the Body of Christ added to the chalice containing the Precious Blood and administered to the faithful with a spoon, and inasmuch as the Precious Blood is never reserved, how is the Eucharist consecrated at a previous service distributed? The answer: the particles of the Eucharist are placed into a chalice containing ordinary wine which is not consecrated for distribution to the faithful with the understanding that, so long as Communion is distributed before the particles completely dissolve, their Eucharistic substance remains. This practice has been long standing for centuries, and has always been approved for the Eastern Catholic Churches. This same manner of distribution is used when taking Holy Communion to the sick, the priest taking with him, along with the Blessed Sacrament, a small chalice, spoon and a container of ordinary wine.

Moreover, even though the Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts does not involve the confection of the Eucharist, the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, promulgated by Pope Saint John Paul II in 1990, authorizes the priest to accept an intention offering (stipend) for this service just as if it was the Divine Liturgy, unless the particular law of the specific Eastern Catholic Church prohibits it. In the Ruthenian Metropolia of the USA, the priest is authorized to accept such an offering provided that the one making the offering is informed that it is for the Presanctified and not for a Divine Liturgy. This does not apply to the Sixth Hour with Holy Communion or the Typica service, for which no offering may be accepted.

†† The Holy Martyr Photina, sometimes called Svetlana or Kyriaka in the Slavonic Churches, is commemorated by a few Eastern Churches on March 20th, along with her sons Victor (Photinos) and Josiah, and their sisters Anatolia, Photo, Photida, Paraskeva, Kyrakia and Domnina. As usual in these cases, there is little actual evidence to substantiate the legends on which the feast is based, and it is not celebrated at all in the Ruthenian Church. The fact that some of Photina's offspring seem to have Slovak names, while she herself was clearly a Samaritan, would tend to indicate that the legends originated in Eastern Europe.

These legends posit that Photina moved to Carthage with her younger son, Josiah, fearlessly preaching the Gospel there, while her older son, Victor, fought against the barbarians as a member of the Roman Legion before being appointed military commander of Attalia in Asia Minor. The story of the family's persecution by the emperor Nero is long and detailed,—much too detailed for the time in which the events supposedly took place—culminating in the entire family being martyred, with Photina herself being, ironically, thrown down a well sometime around the year AD 66.

|