In the Land of the Sighted, the Blind Man Is King.

The Fifth Saturday of Lent.*

Lessons from the alternate feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Michah 7: 7-9.

• Psalm 27: 1, 7-9, 13-14.

• John 9: 10-41.**

… or, lessons from the feria:

• Jeremiah 11: 18-20.

• Psalm 7: 2-3, 9-12.

• John 7: 40-53.

The Fifth Saturday of Lent; and, the Commemoration of Saint Benedict, Abbot.

Lessons from the feria, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 49: 8-15.

• Psalm 9: 14, 1-2.

• John 8: 12-20.

The Fifth Saturday of the Great Fast, known as Akathistos Saturday.***

Lessons from the triodion, according to the typicon of the Byzantine-Ruthenian Rite:

• Hebrews 9: 24-28.

• Hebrews 9: 1-7.

• Mark 8: 27-31.

• Luke 10: 38-42; 11: 27-28.

FatherVenditti.com

|

10:31 AM 3/21/2015 —

Then the eyes of the blind shall be opened, and the ears of the deaf unstopped; then shall the lame man leap like a hart, and the tongue of the dumb sing for joy,

For waters shall break forth in the wilderness, and streams in the desert;

the burning sand shall become a pool, and the thirsty ground springs of water;

the haunt of jackals shall become a swamp, the grass shall become reeds and rushes.

And a highway shall be there, and it shall be called the Holy Way;

the unclean shall not pass over it, and fools shall not err therein (Isaiah 35: 5-8 RSV).

It’s from the Prophecy of Isaiah; and, like most of the books of the prophets in the Old Testament, it’s about two-thirds poetry; and, like most poetry, it can be very difficult to comprehend. But this one is fairly easy: “Then the eyes of the blind shall be opened, and the ears of the deaf unstopped …” He’s prophesying about the coming of the Messiah. And that’s why Isaiah’s prophesy is in the Bible: the eyes of the blind were opened, as we just read.

We mentioned this man, you'll recall, not long ago in the context of the apostles asking our Lord whose sin was responsible for his condition, and we explained why they asked that question, so we're not going to revisit that topic. The question I pose to you today is: what is the difference between going blind and being born blind?  A person who goes blind retains mental images of things he once saw; and, while those images fade and become distorted over time, he still retains enough to help him visualize whatever may be described to him. But the person born blind has no such memories. You can describe something to him; but, depending on what it is, he may or may not be able to form a mental picture. The example I like to give is that of color. Now, here’s something that changes the appearance of a thing, but it’s texture and shape remain the same. A person who has gone blind knows what you’re talking about when you say that something is red or green or blue; but what goes through the mind of the person born blind when you tell him that the sky is blue and the grass is green, or that the moon tonight is a beautiful amber? How does he have any idea what you’re talking about? A person who goes blind retains mental images of things he once saw; and, while those images fade and become distorted over time, he still retains enough to help him visualize whatever may be described to him. But the person born blind has no such memories. You can describe something to him; but, depending on what it is, he may or may not be able to form a mental picture. The example I like to give is that of color. Now, here’s something that changes the appearance of a thing, but it’s texture and shape remain the same. A person who has gone blind knows what you’re talking about when you say that something is red or green or blue; but what goes through the mind of the person born blind when you tell him that the sky is blue and the grass is green, or that the moon tonight is a beautiful amber? How does he have any idea what you’re talking about?

Professor Alice Von Hildebrand, in her book Philosophy of Religion, she says that this is exactly what happens when you try to explain faith to someone who doesn’t believe: you’re speaking a language he doesn’t understand. And I think we often have that same feeling today when we watch or read the news, and the journo is talking or writing about our Catholic religion or the Pope or anything to do with the Church, and using the vocabulary of politics or sociology because he doesn’t know the language of faith. It sounds strange to our ears and can make us feel isolated, almost as if we are sighted people who have wandered into the kingdom of the blind, where no one can understand what we’re trying to tell them.

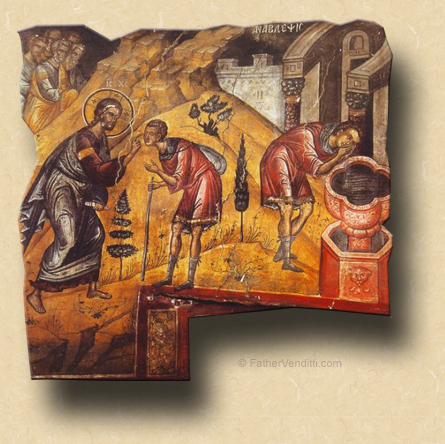

Of course, for St. John, who gives us this account from our Lord’s life in his Gospel, there is a deeply symbolic meaning to our Lord’s encounter with the man born blind. Remember that, in the very beginning of his Gospel, John speaks of man walking in darkness, being unable to see the light even though it is all around him. He describes Jesus as “The true light that enlightens every man …” (John 1: 9); and, this encounter between Jesus and this blind man—which is a real one—took on a deep significance for him, which he tries to pass on to us. Darkness, of course, is sin; darkness from birth is Original Sin; and it is not a coincidence that the man’s sight is restored by washing his eyes with water at the command of our Lord, since it is water which is used to wash away Original Sin in baptism.

And the sequence of events after the man receives his sight is illustrative of the life of every serious Christian. One would think that blindness would tend to isolate someone from society; but, the man here is actually isolated by his sight, by those who do not understand the gift he’s received. He is, in fact, pursued by them as if his new-found sight somehow threatens them. He points out to them their hypocrisy, but this only makes them angrier; so, he is expelled from the synagogue and told he is a sinner. Hearing about this, our Lord tracks him down, where He then asks the quintessential question—the same question He asked the Samaritan woman at Jacob's Well, and the paralyzed man we read about a few days ago at the pool of Bethesda: “Do you believe in the Son of Man?” Do you believe in the Messiah? In all three cases, they ask Him, “Who is he, Lord?” And in all three cases Jesus gives the same answer: “I who speak to you am he.”

That statement, of course, has to be either accepted or rejected; and, in this sense, we can see how the Church on earth is the paralytic, is the Samaritan woman, is especially the man born blind. To each of these people Jesus claims to be God, and demonstrates the fact; and, the Catholic Church is the sole entity on earth that claims to speak for Him and dispense his grace. This angers people, not only today, but in all times down through the centuries. People are willing to tolerate God and those who believe in Him if they keep Him in the closet labeled “personal idiosyncrasies”; but, when such people let God out of the closet and allow Him to influence how they live their lives, how they raise their children, how they conduct their personal and public affairs, how they vote, then people are not so tolerant. And as we struggle each day to live lives motivated by faith in a faithless time, it’s very easy for us to feel alone and isolated, and wonder if there might be something wrong with us.

The reality is that we’re the only healthy ones around; it’s society that’s gone blind; and, when that blindness has become the norm, then the only person who can see becomes the odd man out, and the pressure to conform in order to get along becomes almost too great to bear. One remembers the words that the playwright Robert Bolt put into the mouth of St. Thomas More, when he was asked, “Can’t you come along with us for the sake of fellowship?” and More replied, “When you go to heaven for doing your conscience and I go to hell for not doing mine, will you come along with me for the sake of fellowship?”

The man born blind, whom you would think would have been isolated by his blindness than by anything else, was actually more isolated by his sight, after he received it. He was tolerable in the synagogue so long as he remained blind and the status quo remained unchallenged. Once his eyes were opened, he was able to see the truth: that what was happening in the synagogue was useless, that Jesus is God, and the synagogue does not serve Him. And so it will always be for those who have received the gift of faith. As for those who remain in darkness, we can only continue to ask them again and again, “Do you believe in the Son of Man?” in the hope that, one day, finally weary and worn out by the pursuit of empty lives, they will ask us in return, “Who is He, that I, also, may believe in Him?”

* The Fifth Saturday of Lent is what the Missal refers to as "Saturday of the Fourth Week of Lent." Cf. the note regarding the designation of days on this site, found here.

** The Roman Missal Third Edition provides a single set of alternate lessons which may replace the lessons on any one ferial day this week, provided that the preceding Sunday's lessons were taken from either the secondary or tertiary dominica; the choice of the day on which the set is used—or even if it is used at all—is left to the celebrant. This is done so that the Gospel of the Man Born Blind, which is read only on the previous Sunday when the lessons come from the primary dominica, need not be completely lost on the other two dominical years. I have chosen to use these alternate lessons today.

*** It is customary to sing an ákathist hymn to the Mother of God at Matins on the Fifth Saturday of the Great Fast; however, in parish usage, the ákathist hymn may be sung at any time. It should be noted that the Ákathist to our Most Holy Lady the Theotokos is only one of many ákathist hymns used in the Churches of the Byzantine Rite: six to our Lord, four to our Lady under various titles, eleven to various saints, and one for the repose of the departed are the most commonly used. Cf. The Book of Ákathists to Our Saviour, the Mother of God, and Various Saints, published by Holy Trinity Monastery, Jordanville, New York. An ákathist most closely corresponds to the devotional litanies of the Western Church, e.g., Litany to the Sacred Heart, Litanty to the Most Precious Blood, Litanty of Loretto, etc., of which there are also many. The word "ákathist" comes from the Greek word meaning "to stand," because it is customary for the faithful to stand for the entire service.

Two sets of lessons are indicated for the Divine Liturgy because the commemoration of the Mother of God does not displace the ferial day of the Great Fast; they are sung in the order given.

|