We Should Think Twice before We Join This Parade.

Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord.*

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Luke 19: 28-40.

• Psalm 24.

• Psalm 47.

• Isaiah 50: 4-7.

• Psalm 22: 8-9, 17-20, 23-24.

• Philippians 2: 6-11.

• Luke 22: 14—23: 56.

The Second Sunday of the Passion or Palm Sunday.*

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Matthew 21: 1-9.

• Psalm 147.

• Philippians 2: 5-11.

• Psalm 72: 24, 1-3.

• Psalm 21: 2-9, 18-19, 22, 24, 32.

• Matthew 26: 36-75; 27: 1-66.

Flowery Sunday.

Lessons from the triodion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

[At Matins & the Blessing of the Palms & Willows.]**

• Matthew 21: 1-11, 15-17.

[At Divine Liturgy.]

• Philippians 4: 4-9.

• John 12: 1-18.

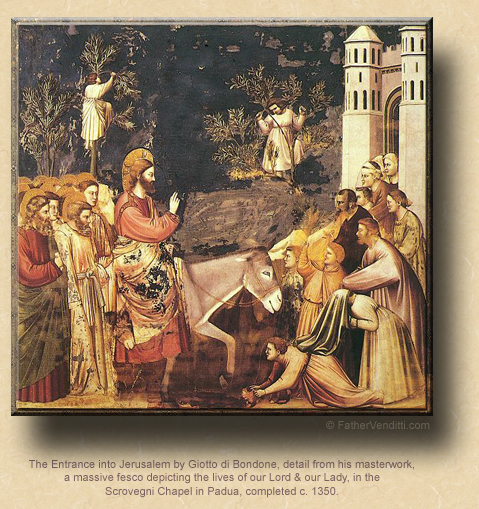

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:12 AM 3/20/2016 — When Mary anoints Jesus with perfumed oil, seemingly out of love and devotion, we realize, as does our Lord, that she’s really anointing Him in preparation for his burial, even though she doesn’t know this. The Jewish custom was to dress the body with perfumed oils prior to burial; but, remember that this could not be done for Jesus after His death because it was the Sabbath and late in the day; that's why Mary, Mary and Salome went to the tomb on Easter Sunday: to perform this ritual retroactively, as it were. They couldn't do it because they found the tomb empty; but, even if our Lord had not yet risen, they couldn't have done it because it had already been done. That made this anointing in the home of Lazarus significant: because it, in fact, was our Lord's burial anointing, even though He was not yet dead. And it becomes obvious that the triumphant procession we remember today was really a funeral procession, even though no one there at the time knew it except Jesus Himself. They wanted to crown Jesus on this day and make Him King; and, He would be King. But the crown He would wear would be a crown of thorns; and His reign as a king would begin with his death. 9:12 AM 3/20/2016 — When Mary anoints Jesus with perfumed oil, seemingly out of love and devotion, we realize, as does our Lord, that she’s really anointing Him in preparation for his burial, even though she doesn’t know this. The Jewish custom was to dress the body with perfumed oils prior to burial; but, remember that this could not be done for Jesus after His death because it was the Sabbath and late in the day; that's why Mary, Mary and Salome went to the tomb on Easter Sunday: to perform this ritual retroactively, as it were. They couldn't do it because they found the tomb empty; but, even if our Lord had not yet risen, they couldn't have done it because it had already been done. That made this anointing in the home of Lazarus significant: because it, in fact, was our Lord's burial anointing, even though He was not yet dead. And it becomes obvious that the triumphant procession we remember today was really a funeral procession, even though no one there at the time knew it except Jesus Himself. They wanted to crown Jesus on this day and make Him King; and, He would be King. But the crown He would wear would be a crown of thorns; and His reign as a king would begin with his death.

We’ve discussed before how the life of our Lord is a prefiguring of the life of the Church—or perhaps it’s more proper to say that the life of the Church mirrors the life of the Savior—and we see many instances of this throughout history with the lives of the martyrs; but, I can’t think of any moment in history where this is more clear than today; and, by now, we should all know, as Holy Week begins, to brace ourselves for the annual onslaught of Discovery Channel shows about the “real” historical Jesus, and how scientists have determined that a freak cold spell froze the Sea of Galilee which enabled our Lord to only pretend to walk on water, and maybe it was a long lost twin brother of our Lord who appeared after the crucifixion fooling everyone into thinking that He had risen from the dead. God only knows what they’ll come up with next. And if none of that is able to entice you to stay home from church on Easter, we can always drag out the sex abuse crisis—that’s always good in a pinch—as if the conduct of the Church’s human representatives has any bearing on the truths of the Faith. What better time to attack Christianity than during the holiest time of the year for Christians? Of course, if you say anything derogatory about any other religion, you’re a bigot; you can’t even draw a picture of the prophet Mohammed without starting a riot somewhere, and then have everyone say how terrible it is that we’re being insensitive to someone’s religious beliefs. You can’t criticize atheists because atheism is protected by the Constitution (or so we’re told), and you can get arrested for criticizing someone’s sexual orientation or their right to an abortion; but Christianity—and the Catholic Church in particular—is fair game; you can hate the Catholic Church all you want. Catholics are the last societal group you’re allowed to hate simply because of who they are and what they believe, and still be considered an enlightened person.

Now, we could go into an analysis of why Christianity, and Catholicism in particular, is so feared and hated in America today, but this is Holy Week, and our purpose here is different.  It suffices to point out that the fear and hatred that we, as Christians, receive from our fellow citizens is no different than the fear and hatred that our Lord received from His fellow citizens which led to His Passion and death on the Cross. It makes sense: truth, after all, cannot be disproved; so, if what you fear is the truth, you can’t attack the message, so you attack the messenger instead. That’s what’s happening to us as Christians now, because that’s exactly what was happening to Jesus when He made his triumphal entry into Jerusalem. It suffices to point out that the fear and hatred that we, as Christians, receive from our fellow citizens is no different than the fear and hatred that our Lord received from His fellow citizens which led to His Passion and death on the Cross. It makes sense: truth, after all, cannot be disproved; so, if what you fear is the truth, you can’t attack the message, so you attack the messenger instead. That’s what’s happening to us as Christians now, because that’s exactly what was happening to Jesus when He made his triumphal entry into Jerusalem.

An interesting tit-bit upon which to reflect is that the people lining the streets of Jerusalem, cheering for Jesus and throwing their palms in His path, were most likely the very same people who, by the end of the week, would be shouting at Pilate for His death. We must begin Holy Week with this perspective: that just as Jesus’ kingship is defined by His suffering and death—just as His power and reign as a king become real in the darkest moments of His Passion—so Jesus is present for us even as we face the darkest moments of our lives. We can’t help, as we relive this week the sufferings of Christ, to think of our own sufferings. But it was through His sufferings that Jesus became a king and achieved the purpose for which He came to earth. Just so, no matter what we may be suffering through in our lives, if we unite that suffering to Christ’s, then it will raise us up just as it did Him.

It’s not easy to believe, sometimes, when we are suffering and feel abandoned. It’s not easy to think that it is precisely through our sufferings that we can receive the greatest graces and blessings, just as it wasn’t easy for Saint John and the other disciples, watching Jesus die on the cross, to believe that their glory and the glory of the Church they would establish, was just beginning.

Those of you who may have taken Latin in high school might remember this phrase:

Lustra sex qui iam peracta,

tempus implens corporis,

se volente, natus ad hoc.

It was a Latin poet, Venantius Fortunatus, in the Sixth Century, expressing the faith of the Church: se volente, natus ad hoc—“freely willed, born for this.” Jesus wants this. He wants this cross. He wants this passion. He wants this suffering. Not because He's a masochist, but because He's a Savior. This is the very reason He came to earth. And as our Lord gazed up along the way to the top of the mount of Golgotha, He saw it all, for He was God: He saw how the cross was to be loved and to be adored because He was going to die on it;  He saw the witnessing saints who, for love and in defense of the truth, were to suffer a similar death; "He saw the triumph and the victories Christians would achieve under the standard of the cross. He saw the great miracles which, with the sign of the cross, would be performed throughout the world. He saw so very many men and women who, with their lives, were going to be saints because they would know how to die like Him, overcoming sin."*** He saw the witnessing saints who, for love and in defense of the truth, were to suffer a similar death; "He saw the triumph and the victories Christians would achieve under the standard of the cross. He saw the great miracles which, with the sign of the cross, would be performed throughout the world. He saw so very many men and women who, with their lives, were going to be saints because they would know how to die like Him, overcoming sin."***

But, that's not all He saw. He saw a lot more. He saw the cross become an enigma once again. He saw future generations of men and women bearing His name—calling themselves "Christians"—paying lip service to the cross upon which He was about to die, trying to live their lives as if it never happened, latching on to this particular thing He said or that particular thing He did before His death, saying, "This is why He came. Live by these words, and you are a Christian." He saw that. He saw us thousands of years before we were born, trying so desperately to have Him without His cross, trying to scull some meaning out of the story of His life which pays no reference to the reason for it.

We've seen how the Church is often attacked during Holy Week, as if the practice of the Christian Faith somehow threatens the balance and symmetry of our secular society, and that this should not surprise us. Was this not exactly how they treated our Lord? Make no mistake: the decision to get rid of Jesus was made long before they dragged Him before the Sanhedrin. He was in the way. The charge brought against him was blasphemy; and when no one came forward to give evidence, they went out and got two people who didn’t even know Jesus and paid them to lie, as we read in the Gospel. Nicodemus was the only member of the Sanhedrin to stand up and say, “This is wrong.” And what did they tell him? They were afraid that, if Jesus continued to grow in popularity, the Romans would intervene and occupy the Temple and take away their power. As Caiaphas said to Joseph of Arimathea in the Gospel of St. John, “…you do not reflect that it is best for us if one man is put to death for the sake of the people, to save a whole nation from destruction” (John 11: 50 Knox), having convinced himself, as despots often do, that what’s best for the country is them; and whatever they have to do to keep themselves in power is a means justified by the ends.

It is, therefore, a blessing in disguise that our Church, and we as individuals, are given the opportunity to suffer as our Lord suffered: victims of those who fear the truth. And if we are able to take that aspect of our Lord’s passion and internalize it, then it can become the means by which we can bear all the crosses that we are forced to carry in our lives.

So, as we relive today this complex scene—the parade of cheers that ends in death—let us contemplate our hardships and sufferings and thank God for them, and resolve to unite them to the sufferings of Christ, and so realize, in spite of how sorry we like to feel for ourselves sometimes, how richly blessed we are by the God who suffered for us.

* In the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, the season of Passiontide, which began last Sunday on the First Sunday of the Passion (or simply Passion Sunday), ends today on the Second Sunday of the Passion, known as Palm Sunday. In the ordinary form, the season of Passiontide has been eliminated, and the liturgical themes of both Sundays of the Passion have been combined into a single Sunday known as Palm Sunday; in fact, in some early editions of the Missal of Bl. Paul VI, Palm Sunday is listed as Passion Sunday. The Roman Missal Third Edition attempts to cover all the bases by designating the Sunday which begins Holy Week as "Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord."

** In the Ruthenian recension, palms and pussywillows are ordinarily blessed at Matins following the singing of the Gospel for Matins and Psalm 50. The Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom follows immediately (or may even be combined with Matins), with the faithful carrying the palms and willows throughout both services. In parishes where Matins are not taken, the blessing of the palms and willows may take place at the beginning of the Divine Liturgy, in which case the Gospel for Matins is not read, and only the prayer of blessing is recited.

In the Ruthenian recension, there is no provision for a Vigil Divine Liturgy on Saturday evening in anticipation of this feast; if, however, one must be taken, it must be combined with Vespers, it must be the Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil the Great, and the blessing of willows and palms should not take place at this service, though an exception might be considered for parishes which, because they share a priest with other parishes, may only have services on Saturday evenings.

In the Byzantine Churches, the Passion of our Lord is not read on this day, nor is it read in its entirety at any service, but is read in stages throughout the services of Holy and Great Week.

*** L. de Palma, The Passion of the Lord.

|