Christ, the Model of Our Faith, Part Two: The Stuff of Which Life is Made. Hebrews 1:10-2:3;

Mark 2:1-12. The Second Sunday of the Great Fast. Formerly known as The Sunday of St. Gregory Palamas; more formerly as The Sunday of Our Holy Father Polycarp. The Holy Martyrs Sabinus & Papas.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

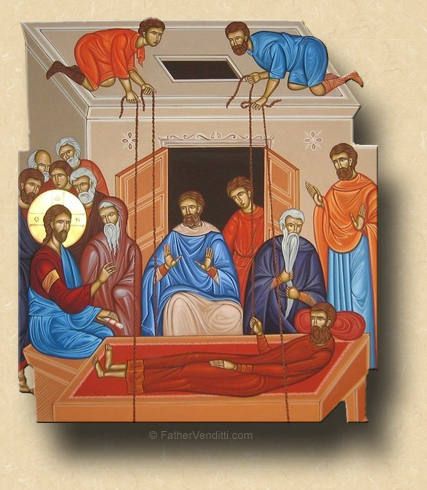

12:44 PM 3/16/2014 — Anyone who knows me knows that I love a good mystery, which is probably why I had no qualms of conscience dispensing with our usual consideration of the familiar Gospel passages of the Great Fast Sundays, as full of important lessons as they are.  Today's Gospel about the crippled man hoisted onto the roof by his friends and lowered through a hole in the ceiling to be cured by our Lord is certainly one of those, suggesting that the perseverance of these men in taking such extreme measures to get their friend to our Lord is something that applies analogously to our own interior life and relationship with God. How many of us have given up or somehow faulted our Lord when we could not get what we wanted in the way we wanted? They had the gift of faith, which is why they brought their friend to our Lord in the first place; but, when they found they couldn't get him in because of the crowd, instead of blaming our Lord for not being accessible enough, they found another way, only this one required some effort. Can there be any doubt that this was intended by our Lord as a message? And is there any doubt that the message is often lost on us, as we tend to treat our Lord as some kind of vending machine, presuming that our prayers have gone unanswered when what we ask of him doesn't come in the way we have conditioned ourselves to expect? Today's Gospel about the crippled man hoisted onto the roof by his friends and lowered through a hole in the ceiling to be cured by our Lord is certainly one of those, suggesting that the perseverance of these men in taking such extreme measures to get their friend to our Lord is something that applies analogously to our own interior life and relationship with God. How many of us have given up or somehow faulted our Lord when we could not get what we wanted in the way we wanted? They had the gift of faith, which is why they brought their friend to our Lord in the first place; but, when they found they couldn't get him in because of the crowd, instead of blaming our Lord for not being accessible enough, they found another way, only this one required some effort. Can there be any doubt that this was intended by our Lord as a message? And is there any doubt that the message is often lost on us, as we tend to treat our Lord as some kind of vending machine, presuming that our prayers have gone unanswered when what we ask of him doesn't come in the way we have conditioned ourselves to expect?

But, as I said, I love a mystery, and the New Testament book presented to us in the Apostolic Readings during the Sundays of the Great Fast is full of it. As we saw last week, not only do we not know who wrote Hebrews, we're not even sure what it is. We did venture a few cautious speculations: the style and beauty of the Greek seems to indicate that the human author grew up speaking that language, so it certainly wasn't the Apostle Paul; and, the only qualified person referenced in the New Testament who fulfills that requirement is Apollos, who succeeded Paul in Corinth; but that doesn't really prove anything. We speculated that the term “Hebrews” was nothing more than an analogous term used by the human author to identify all Christians, since all Christians are exiles in this world as they journey toward the next, because “Hebrews” was how the Jews came to be known during the Babylonian Captivity. Finally, we suggested that the book was intended by its human author as a sermon, only because we know that's how it was used extensively as it circulated throughout the Apostolic Church. None of this, of course, do we know with any certainty. What is not mysterious is the vast depth of theological and spiritual truth God transmits to us in this book, which is so much more important than any hypotheses we might make about its human origins.

But before diving into that, we should take a moment to acknowledge the little bit of mystery surrounding the Second Sunday of the Great Fast, itself. Traditionally, the Sundays of the Great Fast have certain commemorations attached to them: the First Sunday, originally the Holy Prophets, later the Restoration of Icons; the Third Sunday, the Veneration of the Cross; the Fourth Sunday, St. John Climacus, author of the great Lenten treatise, The Ladder; the Fifth Sunday, our Holy Mother Mary of Egypt. But the commemoration traditionally attached to the Second Sunday carries with it a little controversy. For centuries, it was dedicated to St. Gregory Palamas, Bishop of Thessalonica, who died in 1359.  He was declared a saint in Constantinople by Patriarch Philotheus, who had been a disciple of his, and had directed that he be commemorated on this Sunday; but, a later examination of Gregory's writings identified some errors in his theology; not to suggest that he himself was a heretic, but simply careless in this language; and, even though he remains a great saint, many Eastern Catholic Churches, including our own in recent years, have detached his name from the Sunday, even though most Orthodox Churches have not. He was declared a saint in Constantinople by Patriarch Philotheus, who had been a disciple of his, and had directed that he be commemorated on this Sunday; but, a later examination of Gregory's writings identified some errors in his theology; not to suggest that he himself was a heretic, but simply careless in this language; and, even though he remains a great saint, many Eastern Catholic Churches, including our own in recent years, have detached his name from the Sunday, even though most Orthodox Churches have not.

Ironically, prior to Patriarch Philotheus, the Second Sunday had been dedicated to the memory of St. Polycarp, a great theologian, prudent bishop, heroic martyr and Father of the Church who had been a close friend of St. John the Evangelist in his later years, and whose theology has never been in question. A typicon published in Rome in 1963 attempted to reattach Polycarp's name to this Sunday, but it never caught on; and, the typicon of the Ruthenian Church now commemorates no one.

So much for the Byzantine contribution to the ecclesiastical edition of Trivial Pursuit.

Now, if you listened to the Apostolic reading today, I would hope you can see right away why the earliest Christians latched onto the whatever-it-is called Hebrews to nourish their souls during the Lent of old. It also lends credence to the theory that Hebrews was intended as a sermon, as these opening chapters clearly show a preacher's rhythm: the human author oscillates between the joy of the salvation promised by Christ and the consequences for those who don't heed the message, as the first two chapters of Hebrews are laced with a sense of urgency.

You've all seen, I'm sure, the movie Gone with the Wind. Toward the beginning of the film there's a scene which takes place at a party on Seven Oaks Plantation, and the camera pans briefly by a sundial on which are emblazoned the words, “Never squander time; it is the stuff of which life is made.” That could be a one-sentence summation of the first two chapters of Hebrews. The human author reminds us that we need to be ready all the time, asking the quintessential question: am I going to heaven or hell? He doesn't embroil himself in the controversies about when Christ will come again, the way Paul does in some of his letters; he simply states the fact that, whenever it happens, we need to be ready and, if we presume we've got time, we could be caught with our proverbial pants down. Or, as our old friend Dorotheos of Gaza said, “Who will give us back this present time if we waste it?” (Discourse X: “On Traveling the Way of God”).

Think back to the Twenty-second Sunday after Pentecost and our Lord's very harsh parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man: not only does the Rich Man not get a second chance, but he's not even allowed to warn his brothers, as Abraham tells him, “They have Moses and the Prophets; they should need nothing more.” Hebrews says the very same thing:

More firmly, then, than ever must we hold to the truths which have now come to our hearing, and run no risk of drifting away from them. The old law, which only had angels for its spokesmen, was none the less valid; every transgression of it, every refusal to listen to it, incurred just retribution; and what excuse shall we have, if we pay no heed to such a message of salvation as has been given to us? (2:1-3).

What excuse, indeed? And St. John Chrysostom, commenting on this, comforts us by pointing out that the changes we may need to make in our lives to be worthy of salvation need not necessarily be successful, provided that the effort is made now, because God, who searches the heart, recognizes the potential for change simply by reason of the fact that we've made the choice. The only way we can be condemned is if we wait: “If you approach now,” he says, “you will receive both grace and mercy, for you approach 'in due season,' but if you approach then, that is, at the Day of Judgment, no longer will you receive it” (Homily XII on 2 Cor. 6). That's why we're here on this earth: to work out our salvation; but that, as he alludes, is an ongoing task that lasts our whole lives, and is, in fact, the very reason that this life has been given to us: “What is the profit of this present life,” he asks, “when we do not use it for our future gain?” (Homily XC on Matthew).

But the comforting truth we receive from Hebrews, which is not present in the Epistles of St. Paul, but which was so well expressed by the Fathers of the Church, is the realistic notion that none of us can change overnight, nor do we have to. When we go to confession, we know that one of the conditions for receiving absolution is what we call a Purpose of Amendment, but what does that mean? It doesn't mean that we're promising to change; it means simply that we're promising to try. And if my life should be required of me while I'm merely in that process, that would be enough. Even an ascetic as severe as Abba Dorotheos, who said, “Who will give us back this present time if we waste it?” in the same discourse also said, “We are not yet perfect, but at least we desire to be so, and this is the beginning of our salvation.”

And we'll continue with Hebrews next week.

|