Ask not "Who is Jesus to me?" but "Who am I to Jesus?"Heb. 11:24-26, 32-12:2; John 1:43-51. The First Sunday of the Great Fast, also known as the Sunday of the Holy Prophets or the Sunday of Orthodoxy.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

1:02 PM 3/13/2011 — The liturgical celebration of the First Sunday of the Great Fast has gone through an evolution over the centuries; and we've spoken about that in years past. Originally it was a commemoration of the Old Testament prophesies concerning our Lord; hence Philip telling Nathaniel, "We have found Him of whom Moses in the law, and also the prophets, wrote...”; not to mention the reading from Hebrews, which is all about the prophets and their sufferings. Then, following the iconoclastic controversy, the focus of this Sunday changed, and became a celebration of the restoration of the veneration of icons throughout the Church; hence it's still popular title, "The Sunday of Orthodoxy" or "The Sunday of the True Faith."  And, last year, we focused on the Gospel passage itself: our Lord’s first meeting with Nathaniel, how he spied Nathaniel coming from a distance and could immediately read the state of his soul which, luckily for Nathaniel, was “without guile,” as our Lord put it; and from this we meditated on the fact that Christ is able to see into the darkest corners of our hearts, even into places where we ourselves have ceased to look; and I gave you an analogy about our souls being like our computers: we think we have a good fire wall in place, and our anti-virus software is up to date; but our Lord still gets in and is able to see what we think we’ve long since deleted and now forgotten about: a practical Lenten reflection which you can take for what it’s worth. And, last year, we focused on the Gospel passage itself: our Lord’s first meeting with Nathaniel, how he spied Nathaniel coming from a distance and could immediately read the state of his soul which, luckily for Nathaniel, was “without guile,” as our Lord put it; and from this we meditated on the fact that Christ is able to see into the darkest corners of our hearts, even into places where we ourselves have ceased to look; and I gave you an analogy about our souls being like our computers: we think we have a good fire wall in place, and our anti-virus software is up to date; but our Lord still gets in and is able to see what we think we’ve long since deleted and now forgotten about: a practical Lenten reflection which you can take for what it’s worth.

All of these different aspects of this First Sunday of the Great Fast we’ve talked about over the years; so, what’s left? In asking myself that question, I found myself rereading John Chrysostom’s homily on the first chapter of John's Gospel, and came across a little exposition on something that the Evangelist reports in this gospel passage almost in passing: after our Lord tells Nathaniel how he saw him under a fig tree—how he saw the purity of his soul—Nathaniel says to Jesus, “Rabbi, You are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!” Chrysostom points out that the first part of that statement—”Rabbi, You are the Son of God!”—is, word for word, exactly what Peter says to Christ after the miraculous catch of fish; but Peter is responding to a rather impressive miracle. When Nathaniel says it, he hasn’t seen any miracles—unless you want to count Jesus seeing him under the fig tree, which certainly doesn’t rise to the level of raising Lazarus from the dead or giving sight to the blind or even the miraculous catch of fish. Jesus’ public ministry has not yet begun at this point; he’s still collecting his apostles around him. Obviously, when Peter calls Jesus the Son of God, he means something very different than what Nathaniel means. Nathaniel adds to the end of that statement, “You are the King of Israel!” We will never know exactly what Nathaniel meant by that: whether it’s a political statement or reference to a sort of spiritual kingship we don’t know. Certainly, recognizing Jesus as King of Israel—whatever it means—is a far cry from recognizing Him as God. And Chrysostom points out that this is an important point for us: Nathaniel sees Jesus as he is able to see Jesus, having had no previous experience with Him.

Nathaniel disappears from the Gospel after this; we know he is there, but what he may have said or done after this point is not recorded. It’s safe to assume that his understanding of exactly who and what Jesus is grew and developed over time, as it did for all the apostles. Some, like Peter and John, knew early on that Jesus was God;—they had figured it out—some of the others didn’t realize it until after our Lord had risen from the dead. Judas began where Nathaniel may have begun, seeing Jesus as a political figure with spiritual overtones; but when he realizes that there isn’t going to be a revolution to overthrow the Romans, he becomes disillusioned and betrays our Lord. He does realize it at the end, after his betrayal; and that realization drives him to suicide.

What we have to figure out is how we choose to recognize our Lord; and we are all at different stages in that process. People like Jesse Jackson or Jeremiah Wright, both men of the cloth, would see Jesus as a social and political teacher who inspires us to be concerned for the poor and the downtrodden and the oppressed; but I doubt they would see him as any kind of god to whom is owed worship and some form of personal, moral commitment. By contrast, in a previous life I once had a Buddhist coworker who saw in Jesus a spiritual guru with great mystical teachings to impart, but with no understanding of Jesus having any kind of message beyond being at peace with ourselves. The bottom line is: we do not have a right to invent Jesus Christ. He is who he is regardless of what any of us think of him. What we have to figure out is how we choose to recognize our Lord; and we are all at different stages in that process. People like Jesse Jackson or Jeremiah Wright, both men of the cloth, would see Jesus as a social and political teacher who inspires us to be concerned for the poor and the downtrodden and the oppressed; but I doubt they would see him as any kind of god to whom is owed worship and some form of personal, moral commitment. By contrast, in a previous life I once had a Buddhist coworker who saw in Jesus a spiritual guru with great mystical teachings to impart, but with no understanding of Jesus having any kind of message beyond being at peace with ourselves. The bottom line is: we do not have a right to invent Jesus Christ. He is who he is regardless of what any of us think of him.

Three thousand years before God became a man in the person of Jesus Christ, God and man had the first really meaningful conversation with one another since Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden: Moses approached the burning bush* and asked, “Who are you?” And what were God’s first words to man? “I am Who I am!” And God has never changed his identification of himself. When he appeared to Jeremiah the Prophet, he said, “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you.” When the Man Born Blind asked him where he could find the Messiah, Jesus said, “I who speak to you am he.” When Jesus spoke to Saul on the road to Damascus, Saul asks, “Who are you, Lord?” And God’s response: “I am He whom you are persecuting.” The Epistle to the Hebrews: “Jesus Christ: yesterday, today and the same, forever.” We do not define Christ. He defines us.

As for those who still choose to make up Jesus for themselves to suit their own agendas, St. John probably said it best: “He was in the world, and the world was made through Him, yet the world did not know Him. He came to His own, and His own did not receive Him. But to those who did receive Him, He gave the right to become children of God” (John 1:10;12). And if you are searching for some theme to guide your observance of the Great Fast this year, you might consider this: ask yourself not “Who is Jesus to me?” but “Who am I to Jesus?” Are you Cain, being asked by God, “Where is your brother?” Are you Elijah, looking for God in the magnificence of nature and missing him standing right there next to you? Are you Judas, looking for Jesus to solve the world’s problems? Are you Peter, looking for God to save you as you sink into the sea? Are you Nathaniel, who doesn’t know what Jesus is, but only knows, at this point, that he is something different? You’ve only had six thousand years of revelation to figure it out. The first step is to let Jesus define himself. The next step is to then let Jesus define you.

Father Michael Venditti

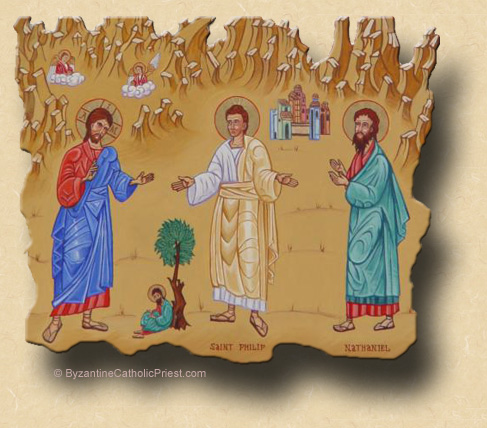

* While the first icon accomanying this post is a simple depiction of Philip introducing Nathaniel to Jesus who had seen him under a fig tree, the second icon requires exposition, as it is a seminal example of the precise Christology embraced by the Eastern Churches. While it appears on the surface to be a straight-forward icon of the Theotokos of the Sign (Mary with Jesus in her womb), it is, in fact, a depiction of the Burning Bush, and comes from an idea presented by the 4th Century Father of the Church, St. Gregory of Nyssa, in his Life of Moses.

St. Gregory writes: “What was prefigured at that time in the flame of the bush was openly manifested in the mystery of the Virgin. [...] As on the mountain the bush burned but was not consumed, so the Virgin gave birth to the light and was not corrupted.” But the analogy of the bush that is burned but not consumed not only expostulates the mystery of the Virgin Birth; St. Gregory believed that Moses may have even been able to see into the future in that moment in which the presence of God burned within the bush. For Saint Gregory, even Moses was looking toward what was to come.

The iconography of the Eastern Churches does not simply portray scenes; it transmits through the ages the unapologetic Christological faith of the Early Church. Jesus is not simply a good man; he is the same God who appeared to Moses.

|