How Many Troubles Thou Hast! But Only One Thing is Necessary.Hebrews 6:13-20 (for the Sunday) & Ephesians 5:9-19 (for the saint); Mark 9:17-31 (for the Sunday) & Matthew 4:25-5:12 (for the saint).* The Fourth Sunday of the Great Fast, known as The Memory of Our Holy Father John Climacus (John of the Ladder). The Holy Martyr Codratus & His Companions.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

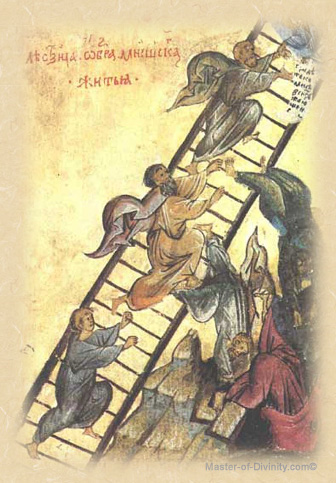

12:46 PM 3/10/2013 — As I’m sure you’ve noticed, some of the Sundays of the Great Fast are dedicated to specific people or specific spiritual ideas. Last Sunday focused on the Veneration of the Holy and Life-giving Cross. Next Sunday is dedicated to the very ascetic Mary of Egypt, who left a life of sin to retreat into the solitude of the desert to do penance. Today we are asked to consider St. John Climacus, which isn’t, of course, his real name. Climacus means “of the ladder.” The abbot of Mt. Sinai and regarded as one of the founders of monasticism in the Christian East, shortly after his death—and maybe a little during his life—he was referred to as “John of the Ladder” because he chose to explain the spiritual life in terms of a ladder: each rung of spiritual perfection must be stepped on safely and securely before one can proceed to the next, and if one climbs steadily one will eventually reach heaven. He was born in the 7th century, and lived a life marked by such explicit penance that the Eastern Churches have taken to setting him up as an example for all of us during the Great Fast. His actual feast day is on the 30th of this month; but, since his book, The Ladder of Divine Ascent,** is typically read in monasteries throughout the Great Fast, a Lenten Sunday dedicated to his memory seemed logical. I've been reading parts of The Ladder myself as spiritual reading for Lent this year. A lot of it pertains specifically to monastic life, but most of it can be applied to anyone in any walk of life. 12:46 PM 3/10/2013 — As I’m sure you’ve noticed, some of the Sundays of the Great Fast are dedicated to specific people or specific spiritual ideas. Last Sunday focused on the Veneration of the Holy and Life-giving Cross. Next Sunday is dedicated to the very ascetic Mary of Egypt, who left a life of sin to retreat into the solitude of the desert to do penance. Today we are asked to consider St. John Climacus, which isn’t, of course, his real name. Climacus means “of the ladder.” The abbot of Mt. Sinai and regarded as one of the founders of monasticism in the Christian East, shortly after his death—and maybe a little during his life—he was referred to as “John of the Ladder” because he chose to explain the spiritual life in terms of a ladder: each rung of spiritual perfection must be stepped on safely and securely before one can proceed to the next, and if one climbs steadily one will eventually reach heaven. He was born in the 7th century, and lived a life marked by such explicit penance that the Eastern Churches have taken to setting him up as an example for all of us during the Great Fast. His actual feast day is on the 30th of this month; but, since his book, The Ladder of Divine Ascent,** is typically read in monasteries throughout the Great Fast, a Lenten Sunday dedicated to his memory seemed logical. I've been reading parts of The Ladder myself as spiritual reading for Lent this year. A lot of it pertains specifically to monastic life, but most of it can be applied to anyone in any walk of life.

But, of course, like many of the saints of the early Church, John Climacus was a monk. He didn’t have a family, he didn’t have a normal job, he didn’t have most of the responsibilities that most of us in today’s world have; so, how could the life of this 7th century monk possibly serve as an example of any value to us, other than just one of general holiness? In that question, of course, is the great error of the modern age. In fact, it’s the error of every age, since every age believes itself to be superior to the past, just like every child grows up believing that he is far smarter than his parents.  And, besides, with so much going on in the world today, the combination of our own personal responsibilities and struggles with the distraction of world events tempts us to simply not bother listening to someone sitting on a mountain in the middle of the desert in the 7th century contemplating how the spiritual life is like the rungs of a ladder. And, besides, with so much going on in the world today, the combination of our own personal responsibilities and struggles with the distraction of world events tempts us to simply not bother listening to someone sitting on a mountain in the middle of the desert in the 7th century contemplating how the spiritual life is like the rungs of a ladder.

But then we hear the words of today’s first Gospel, in which our Lord says something very curious and extremely important. It is, of course, an account of how our Lord helped a boy who was possessed by a very malicious demon. He’s brought to our Lord by his father, who explains that he wouldn’t have bothered our Lord with this problem except that he did take the boy to our Lord’s disciples and they couldn’t help him. So, our Lord exorcises the demon and restores a normal life to the boy, and everyone’s happy. And after it’s all over, the disciples go to our Lord and ask how come they couldn’t do it. And our Lord tells them that this kind of demon—whatever kind that is—can only be driven out by prayer. In other words, here was a very practical problem that turned out, in the end, to have a spiritual solution. And this is where the example of not only John Climacus but also John Chrysostom, Basil the Great, Mary of Egypt, and all the other holy monks and bishops and prophets and ascetics and mystics we revere so highly in our Church, are not only relevant to us today, but what they have to say is more important than what anyone else has to say.

To be sure, we have spoken on occasion here about current events and what they mean for us as Christians, but not extensively; and, that’s because, compared to the interior life, nothing else is really that important. Nothing is more important than being right with God; because, if we’re right with God, then nothing that can happen to us, no matter how terrible, can truly harm us in those things that truly matter; and, if we are not right with God, then nothing matters at all, since the very purpose of living in this world is to prepare ourselves for the next.

That is not an easy thing to remember when all of life is exploding around us with excitement and tragedy. But, then, consider the man who’s boy was possessed. There, certainly, was a very heartbreaking problem both for the boy and his father; and the solution turned out to be what? No less than prayer.

Remember what our Lord said when he was visiting the home of his friend, Lazarus, whom he had just raised from the dead? Lazarus had two sisters, Martha and Mary; and, Martha was busying herself with making her guests comfortable, while Mary ignored her duties as a hostess and was just sitting and listening to our Lord. And Martha complained. And what did our Lord tell her? “Martha, Martha, how many troubles thou hast! But only one thing is necessary” (Luke 10:41). Well, we may have many troubles and are anxious and upset over a lot of things. Other things in life may be important relatively speaking, but there’s only one thing in life that is truly necessary. The whole point of the Great Fast is to help us make sure that, no matter what else may be going on in our lives or in the world, we never lose focus on that one necessary thing.

* In the Byzantine Churches, unlike in the Latin Church, when two or more commemorations fall on the same day, the liturgical texts of all of them are used in succession rather than simply choosing the most important and surpressing the others. The Fourth Sunday of the Great Fast is always dedicated to the memory of John of the Ladder; thus, two Apostlic readings and two Gospels are always read. Moreover, when reading the two Epistles, the cantor announces only the title of the first, then sings both of them run together as one; likewise, the priest or deacon does the same when proclaiming the Holy Gospel.

** A new and excellent translation of this spiritual classic was published by Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Boston, Massachusetts, in 2012, and is available from them.

|