Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, Who's the Fairest One of All?

The Second Sunday of Lent.

Lessons from the secondary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Genesis 22: 1-2, 9-13, 15-18.

• Psalm 116: 10, 15-19.

• Romans 8: 31-34.

• Mark 9: 2-10.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Thessalonians 4: 1-7.

• Psalm 24: 17-18.

• Psalm 105: 1-4.

• Matthew 17: 1-9.

The Second Sunday of the Great Fast; the Feast of the Venerable Martyr Eudoxia; and, the Feast of Our Holy Father David, Enlightener of Wales.**

Lessons from the triodion, according to the typicon of the Byzantine-Ruthenian Rite:

• Hebrews 1: 10—2: 3.

• Mark 2: 1-12.

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:50 AM 3/1/2015 — As you can tell, we're still without heat here at the Shrine, so I'm going to do my best to keep today's homily mercifully short. 9:50 AM 3/1/2015 — As you can tell, we're still without heat here at the Shrine, so I'm going to do my best to keep today's homily mercifully short.

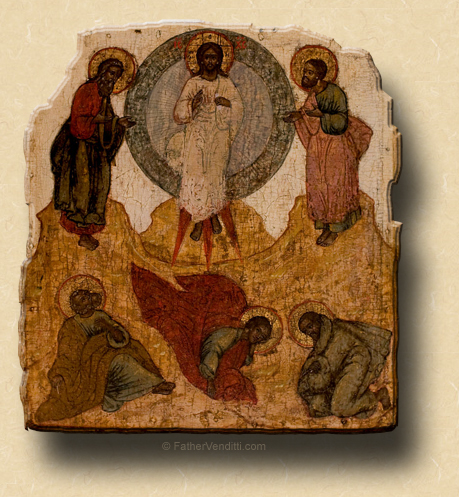

One could legitimately ask why we are given to hear this account of our Lord's glorious Transfiguration on Mount Tabor during the Holy Season of Lent, which is supposed to be penitential in nature; and, there are a couple of reasons. First, the vision of our Lord in His heavenly glory shows him flanked by the two great prophets of the Old Testament: Moses and Elijah, both of whom began their work for God by fasting in the desert for forty days, as did our Blessed Lord just prior to beginning His public ministry; so, that connection to Lent should be obvious. But there's a second reason that often escapes notice.

Only three of our Lord's disciples are permitted to see this vision: Peter, James and John. Now, think carefully. In what other episode of our Lord's life on earth are these three Apostles shown to be alone with Jesus? The answer, of course, is during His Agony in the Garden, which we shall hear about on Good Friday when Lent is over; and, if you are able to expand your mind to see our Lord's life as a whole, then these two events become somewhat like bookends to the most significant part of our Blessed Lord's life on this earth: the one, a manifestation of His Divinity, as He appears to them in His heavenly glory; the other, a profound witness to His humanity, as he weeps in recognition of the great cross by which He is to suffer and die. And here at the Shrine, where we are focused so intently on our Lady's requests at Fatima to pray the Holy Rosary, and where we pray it every day before Holy Mass, it isn't difficult for us to incorporate this into our Lenten reflections.

We all have our favorite images of our Blessed Lord that form the substance of our own personal devotion: Jesus as a child in the manger; Jesus as a young man preaching and calling around him his first disciples; Jesus performing many cures and miracles; Jesus going so willfully to his passion and hanging on the Altar of the Cross; but, these are all images of Jesus in his incarnation; and, there must be—or perhaps it's better to say there should be—a longing deep within us to see Jesus as he really is. Not to suggest that he wasn't really here, because he was, and still is in the Blessed Eucharist; but, we all know that Jesus now is enthroned in His heavenly glory, and that we won't see Him that way until, God willing, we join him there. Only then, as Saint Paul said, will we truly see him not as “a confused reflection in a mirror…[but] face to face” (I Cor. 13: 12 Knox).

I like to think that this was the idea that prompted Pope Saint John Paul II to include the Transfiguration among the Luminous Mysteries of the Rosary: to help us realize that the Jesus we so often pray to, the familiar images of whose life on earth form the basis of our devotional life, is an image of our Lord that is incomplete. Peter, James and John were granted a vision of Christ in His completeness in the Transfiguration, but it was still just a vision; they wouldn't come to see the real thing until they themselves entered into their own heavenly glory, as we hope to one day. And this is why the creation of the Luminous Mysteries by the saintly Pope is so significant: because all of them—the Theophany at our Lord's Baptism, the first miracle at the Wedding at Cana, the Proclamation of the Kingdom of God, the Transfiguration, and especially the Institution of the Most Holy Eucharist—are all elements of our Lord's life that force us to wrench our thoughts out of this world and into the next. Not to say that the other mysteries don't do that; certainly there are heavenly realities to be considered in the Annunciation, the Assumption, the Coronation, not to mention the Resurrection of Christ himself; but, there is something about the Luminous Mysteries that propels us in our prayer into another world, that forces us to rise up in prayer out of an exclusively incarnational approach to our faith, and realize that we are only pilgrims on this earth, and that, one day, we will leave all this behind.

But, as I said, there are two heavenly bookends to our Lord's life: these three favorite Apostles, whom we envy because they were permitted to see this great vision of our Lord in his heavenly glory, couldn't simply walk away with that; they had also to be present at the Agony in the Garden, and that's because the road to heaven is the Way of the Cross. And it's important to note, I think, that this magnificent vision doesn't last but for a few moments. The three Apostles cover their faces as our Lord's face shines like the sun and his garments become as white as light; but, no sooner do they look up and it's over, and there they are alone with Jesus—Moses and Elijah having gone back to their lunch or whatever they were doing in heaven—and it's time to go back down the mountain and get on with the work at hand.

And don't we all have moments like that? An inspiration will come to us—because of a sermon we heard or a book we read or maybe something that came to us in prayer—and it fills us with a momentary joy, and perhaps even causes a new resolution in us to do something or to adopt a new attitude toward our own spiritual combat; but, it's over as soon as it happens. That's the Mystery of the Transfiguration. And it should not disturb us, because that's what our Lord intends all along, just as He knew that the three Apostles who were permitted to witness the Transfiguration would have to witness Him weep in the Garden, too. The one makes the other necessary; the other makes the one possible; both together point us in the right direction, which is to orient our life toward heaven. And is that not what Lent is all about?

We don't often pay attention to it—and we miss it altogether if there is a hymn—but the Introit of today's Mass is particularly appropriate; it's from Psalm 26: Exquisivit te facies mea; faciem tuam, Domine, requiram. Ne avertas faciem tuam a me.... “I have eyes only for thee; I long, Lord, for thy presence. Do not hide thy face from me” (vs. 8 & 9).* It's the most daring prayer in the Bible. Why? Because when one sees God as He is, by necessity one must also see himself as he is, and that could be a terrible prospect. And I'm not the first person to suggest that, on the day of Judgment, God doesn't pronounce judgment on us; we pronounce judgment on ourselves. Christ holds up a mirror, and we see our souls as they actually are, all the excuses and rationalizations stripped away, and our place in Purgatory is determined by the degree to which we recoil from ourselves in disgust. Why did Moses have to avert his face from the burning bush? Why did Elijah cover his face with his cloak? Why did the favored three apostles, Peter, James and John, have to turn their faces away after the briefest of glimpses? It wasn't simply because the brightness of the vision hurt their eyes;—that's just a metaphor—it's because one cannot look at pure holiness without being destroyed by it … unless one is, oneself, already holy.

The longing to see the face of God is a two edged sword. See it in sin and it damns you; see it in holiness and it saves you. And if that isn't a suitable Lenten meditation, I don't know what is. Our one purpose for being on this earth is to work out our salvation. Nothing else matters.

* My own translation. The Latin is from the Clementine Vulgate, not the Psalter of Pius XII used in the Missal.

** The commemoration traditionally attached to the Second Sunday of the Great Fast carries with it a little controversy. For centuries, it was dedicated to St. Gregory Palamas, Bishop of Thessalonica, who died in 1359. He was declared a saint in Constantinople by Patriarch Philotheus, who had been a disciple of his, and had directed that he be commemorated on this Sunday; but, a later examination of Gregory's writings identified some errors in his theology; not to suggest that he himself was a heretic, but simply careless in his language; and, even though he remains a great saint, many Eastern Catholic Churches, including the Ruthenian Church, have detached his name from the Sunday, even though most Orthodox Churches have not.

Ironically, prior to Patriarch Philotheus, the Second Sunday had been dedicated to the memory of St. Polycarp, a great theologian, prudent bishop, heroic martyr and Father of the Church who had been a close friend of St. John the Evangelist in his later years, and whose theology has never been in question. A typicon published in Rome in 1963 attempted to reattach Polycarp's name to this Sunday, but it never caught on; and, the typicon of the Ruthenian Church now commemorates no one.

|