The Parting of Friends, Part Two.

The Fifth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the secondary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Job 7: 1-4, 6-7.

• Psalm 147: 1-6.

• I Corinthians 9: 16-19, 22-23.

• Mark 1: 29-39.

Sexagesima Sunday.*

Lessons from the dominca, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• II Corinthians 11: 19-33; 12: 1-9.

• [Gradual] Psalm 82: 19, 14.

• [Tract] Psalm 59: 4, 6.

• Luke 8: 4-15.

FatherVenditti.com

|

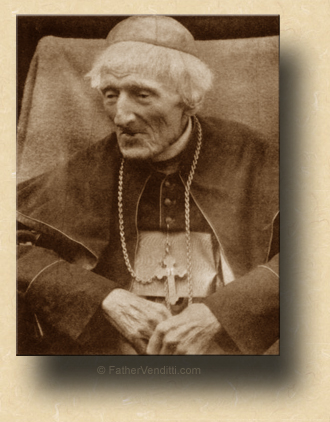

8:28 AM 2/4/2018 — The very first homily I preached here at the Shrine was on Pentecost Sunday, 2014, and at the end of it, I quoted Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman; and, when I posted the homily later that day on my web site, I named it after the last line of that quote: “Let not this sacred season leave us as it found us.” Today I preach my last homily here at the Shrine, as this Tuesday I leave you to return to my home parish in Maryland to be close to my family and particularly my mother who needs a lot of care, and I’m going to begin it with Cardinal Newman: 8:28 AM 2/4/2018 — The very first homily I preached here at the Shrine was on Pentecost Sunday, 2014, and at the end of it, I quoted Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman; and, when I posted the homily later that day on my web site, I named it after the last line of that quote: “Let not this sacred season leave us as it found us.” Today I preach my last homily here at the Shrine, as this Tuesday I leave you to return to my home parish in Maryland to be close to my family and particularly my mother who needs a lot of care, and I’m going to begin it with Cardinal Newman:

When the Son of Man, the First-born of the creation of God, came to the evening of His mortal life, He parted with His disciples at a feast. He had borne “the burden and heat of the day;” yet, when “wearied with His journey,” He had but stopped at the well's side, and asked a draught of water for His thirst; for He had “meat to eat which” others “know not of.” His meat was “to do the will of Him that sent Him, and to finish His work;” “I must work the works of Him that sent Me,” said He, “while it is day; the night cometh, when no man can work.” Thus passed the season of His ministry; and if at any time He feasted with Pharisee or publican, it was in order that He might do the work of God more strenuously.

Those words were preached by Cardinal Newman under very difficult circumstances. At the time, he was the Anglican chaplain of Oxford University; and, as pastor of the university parish, he was responsible not only for the spiritual welfare of the students and faculty, but also for the servant class who catered to them. He rarely got the opportunity to preach on Sunday morning at the university church because there was usually a guest preacher; but, with money he had borrowed from his mother, he built a small chapel off the university grounds in the neighborhood of Littlemore, in which he provided Vespers for the “lower-born” members of his flock; and there he could preach.

The day that sermon was preached was an auspicious occasion, as it was the anniversary of the dedication of that chapel at Littlemore; but, for John Henry Newman, it was an even more important day:  it was the day he had made the decision to leave the Church of England and embark on a spiritual journey which would, in just a few years time, see him received into the Catholic Church. He entitled the sermon “The Parting of Friends.” it was the day he had made the decision to leave the Church of England and embark on a spiritual journey which would, in just a few years time, see him received into the Catholic Church. He entitled the sermon “The Parting of Friends.”

The last time I was in this situation, just before coming here nearly four years ago, I took the occasion to preach a long, rambling homily which reminisced about all the major events that had taken place during my years in the two parishes of which I was pastor, thanked all the relevant people who needed to be thanked, reminded my parishioners of so many points I wanted them to remember, and encouraged them to love and respect the priest who followed me. I'm not going to do that this time because, first of all, I don't have the physical or emotional strength to do it, but also because you don't need to hear it. The events that have taken place we all remember; the people whom I would thank have never asked for or sought after thanks; and, if you show Father James even half of the love, devotion, respect and cooperation that you've shown me over the years, he will do well, and you will do well under his kind and gentle spiritual guidance.

But, you know me; I’m not easily distracted from commenting on the Scripture lessons of the day, and it just so happens that—whether by chance or Providence—today’s lesson serves as a good summation of much of what I’ve tried to teach you during my years here. Many of the Gospel lessons that come our way in Ordinary Time, particularly in the first few weeks, can seem pedestrian and commonplace until we resolve to read them with prayerful recollection. The characterization given from the seasons of Christmas and Epiphany is one of Divine mystery; we were maneuvered by the liturgy of the Church to reflect on the Divine in Christ: His preexistence from all eternity, His fulfillment of Old Testament prophesy, the mystical nature of His earthly conception and birth. The contrast of that with the Gospel lessons in the beginning of Ordinary Time would lead us to believe that the shift is changing dramatically from Who and What Jesus is to what it is He does: not so much Jesus being this or that, but Jesus doing this or that … all kinds of activity: preaching, traveling, curing. But then comes the one solitary verse that cures us from judging too rashly or over-simplifying things.

Our Blessed Lord is busy in today's lesson: Peter's mother-in-law is ill, so he goes and cures her; and that, of course, is the cue for everyone in town to drag all their sick and possessed to our Lord, so the day is spent dealing with them. Lord knows how many of these people were actually possessed. Some mother has an unruly kid she can't control, so she presumes he's possessed even though anyone raised by someone as high-strung as her would have to turn out peculiar. My assumption is that very few of these people actually believed in our Lord. How could they? He's revealed precious little about Himself at this point. It reminds me of Henry VIII's wonderful line from Robert Bolt's play, A Man for All Seasons:  “There are those like Norfolk who follow me because I wear the crown; and those like Master Cromwell who follow me because they are jackals with sharp teeth and I'm their tiger; there's a mass that follows me because it follows anything that moves.” I think there were a lot of those following our Lord in the early days of His ministry. “There are those like Norfolk who follow me because I wear the crown; and those like Master Cromwell who follow me because they are jackals with sharp teeth and I'm their tiger; there's a mass that follows me because it follows anything that moves.” I think there were a lot of those following our Lord in the early days of His ministry.

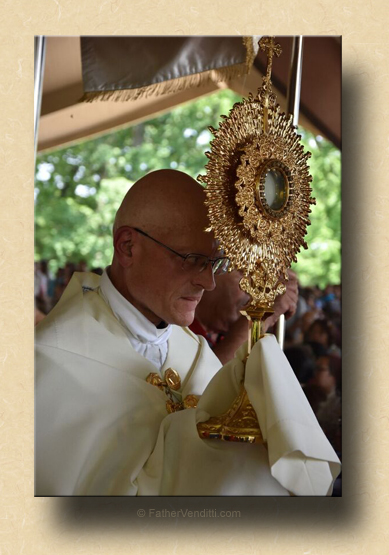

In any case, he spends the day with these people, even if they are “a mass that … follows anything that moves”, and gives them what they want: “various diseases” says the Gospel, and “many demons”; he deals with it all. But when the day is done: “Rising very early before dawn, he left and went off to a deserted place, where he prayed” (Mark 1: 35 NABRE). In spite of the level of activity that the necessity of the moment has imposed on Him, our Lord is not an activist; He's a contemplative. His activity is never allowed to displace His prayer. And the lesson is unmistakable: there is no competition between action and contemplation; and, if we perceive in our lives some tension between prayer and active duty, it's only because we've failed to understand either. If you haven't read it already, get your hands on a book called, The Soul of the Apostolate by Dom Jean-Baptiste Chautard. It was first published in 1920, and was a favorite of Pope Saint Pius X: a whole book dedicated to the thesis that your prayer life can't compete with your daily duty because it's your prayer life that gives meaning to everything you do.

Of course, our Lord doesn't escape for long; the disciples have followed Him: “Everyone is looking for you” (v. 37). It's more than just Saint Mark listing the sequence of events; it's a statement of eternal truth. Think about it long enough and you'll realize it: everyone is looking for Jesus, even those who don't know that He's the one they're looking for, even those who don't know they're in fact looking for anything. The words of Saint Augustine at the beginning of the Confessions may be the most truthful post-Biblical statement every made: “Thou hast made us for Thyself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee” (Conf., Book I, ch. 1). The human heart is made to seek and to love God. And God facilitates this encounter, for He, too, seeks out each one of us through countless graces; hence, our Lord's statement after He is found: “Let us go on to the nearby villages that I may preach there also. For this purpose have I come” (v. 38). And He's not just telling us about Himself; He's telling us about ourselves, giving us an example.

When we see someone, or read about someone in the paper, or see something about someone on television, the thought often crosses the back of our mind: “Does that person worry about salvation?” We may even say a silent prayer for that person, or that situation, or the world in general. It's that apostolic seed that the Lord has planted deep in the soul of each one of us, and our first instinct is to pray. We may even find ourselves feeling guilty: “Should I be doing more?” But what is it we think we should do? Quit our jobs to go fight ISIS? Abandon our responsibilities to care for poverty-stricken countries? Make a spectacle of ourselves preaching on a soap box to the pagans in Times Square? Certainly not.  Our duty is here with those who depend on us. Give in to the temptation to believe that prayer is not a sufficient response, and you've given in to the activist mentality that Dom Chautard warns about. Our first duty before God is to meet faithfully the responsibilities of the here and now, and sanctify that duty through prayer. Our duty is here with those who depend on us. Give in to the temptation to believe that prayer is not a sufficient response, and you've given in to the activist mentality that Dom Chautard warns about. Our first duty before God is to meet faithfully the responsibilities of the here and now, and sanctify that duty through prayer.

Let's take the Lord's example. He did a lot of good for a lot of people, as these lessons in the beginning of Ordinary Time illustrate; but, he always took time to pray; and, sometimes I don't wonder, whenever I read that passage from Luke wherein our Lord's visit to Martha and Mary is described, Jesus, in His Human Heart, looking back to these first months of his public life, had just a tinge of envy when he spoke those words to Martha: “Martha, Martha, thou art careful, and art troubled about many things: But one thing is necessary. Mary hath chosen the best part....” (Luke 10: 41-42 Douay-Rheims).

And there you have the last reflection on the Holy Gospel you will hear from me. Just as Cardinal Newman exhorted his congregation on Pentecost not to let the Easter Season leave them as it found them, so I pray that my brief time here with you does not leave you as it found you. Certainly I do not leave you as you found me when I first came here. But, as painful as it is for me, the time has come to say goodbye.

As I leave here, I ask of you only one thing:—aside, of course, for your prayers, which I'm sure I already have—and that is that you not forget me, in the hope that this occasion is, as it should be, “The Parting of Friends.”

As I began this last homily in this beautiful Shrine with the words of Cardinal Newman, allow me to end it in the same way, the way he ended his last sermon to the congregation in Littlemore:

And, O my brethren, O kind and affectionate hearts, O loving friends, should you know any one whose lot it has been, by writing or by word of mouth, in some degree to help you thus to act; if he has ever told you what you knew about yourselves, or what you did not know; has read to you your wants or feelings, and comforted you by the very reading; has made you feel that there was a higher life than this daily one, and a brighter world than that you see; or encouraged you, or sobered you, or opened a way to the inquiring, or soothed the perplexed; if what he has said or done has ever made you take interest in him, and feel well inclined towards him; remember such a one in time to come, though you hear him not, and pray for him, that in all things he may know God's will, and at all times he may be ready to fulfill it.

* Almost all liturgical traditions observe a pre-Lenten season, with the sole exception of the ordinary form of the Roman Rite.

The extraordinary form of the Roman Rite observes a pre-Lenten period lasting for three weeks, known as the Septuagesima Season, consisting of Septuagesima, Sexagesima and Quinquagesima. In English speaking countries, this season is sometimes called “Shrovetide,” because it ends on the day before Ash Wednesday, which is often called “Shove Tuesday.”

The Churches of the Byzantine Rite observe a pre-Lenten season known as the Triodion, lasting for four weeks; it is sometimes preceded by a Sunday “before the Triodion,” as determined by the date of Easter. The first few Sundays of this season are thematic, taken from the Gospel of the day, from which each Sunday gets it’s name. The Sunday before the Triodion is known as the Sunday of Zacchaeus, the First Sunday that of the Publican and Pharisee, and the Second that of the Prodigal Son. The last two Sundays are named after the specific food items which may be eaten during the weekdays prior to them, as the fasting discipline of Lent is gradually imposed: the Sunday of Meatfare and the Sunday of Cheesefare. The day following Cheesefare Sunday is the First Day of the Great Fast, there being no tradition of an "Ash Wednesday."

A pre-Lenten season is also preserved in some of the more traditional branches of the Anglican and Lutheran communions, making the ordinary form of the Roman Rite the only major liturgical Tradition to have completely eliminated it.

|