A Holy Life with an Ulterior Motive is not Necessarily a Bad Thing.

The Eighth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the primary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 49: 14-15.

• Psalm 62: 2-3, 6-9.

• I Corinthians 4: 1-5.

• Matthew 6: 24-34.

Quinquagesima Sunday.*

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Corinthians 13: 1-13.

• [Gradual] Psalm 76: 15-16.

• [Tract] Psalm 99: 1-2.

• Luke 18: 31-43.

Cheesefare Sunday, known as the Sunday of Forgiveness.*

Lessons from the triodion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Romans 13: 11—14: 4.

• Matthew 6: 14-21.

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:01 AM 2/26/2017 — The difficulty with finding a relevant meaning from some of these Gospel passages has a lot to do with the art of translation. Matthew’s Gospel is a problem in particular, because it’s the only book of the Bible written in what is now a dead language. The other Gospel’s were written in Greek; Matthew’s was written in Aramaic, the common Hebrew dialect spoken by our Lord. Those of you who saw Mel Gibson's movie, The Passion of the Christ, heard that language being spoken. 8:01 AM 2/26/2017 — The difficulty with finding a relevant meaning from some of these Gospel passages has a lot to do with the art of translation. Matthew’s Gospel is a problem in particular, because it’s the only book of the Bible written in what is now a dead language. The other Gospel’s were written in Greek; Matthew’s was written in Aramaic, the common Hebrew dialect spoken by our Lord. Those of you who saw Mel Gibson's movie, The Passion of the Christ, heard that language being spoken.

The word in question, which causes the difficulty in this passage, is the one which the Roman Missal accurately indicates as “mammon”; and, while it’s almost always translated as “wealth” or “money,” it means something more than that. One of the frustrations in trying to learn some of these ancient languages is that there are so many different words which the Lexicon translates in the same way, because each of them connotes something unique. So, in your Bible the word reads as “money,” and in English money is money. But in Aramaic you may have twelve different words that mean money, and each one says something different about it or the person who owns it or uses it. Mammon is wealth or money, but with a certain quality of personification. When it’s used as the object of a sentence, it implies some kind of reciprocal human-like relationship to the subject of the sentence. So when one possesses mammon, one not only possesses money but is also possessed by it.

Which kind of sums up our Lord’s whole point, doesn’t it? Saint John Chrysostom explains for us exactly how the choice of this word defines the whole meaning of our Lord’s narrative. It’s not the possession of the wealth that’s the problem; it’s the possession that the wealth holds over us that’s the problem. The Greek and Aramaic languages give you the option of speaking about inanimate objects as persons because it is a fact of life that such objects can become virtual “persons” to those who desire them. Money becomes mammon when obtaining or preserving it becomes the focus of your life, a relationship which should exist only with another person. It’s all right to be devoted to your husband or your wife, it’s all right to be devoted to your children, it’s all right to be devoted to God, but to be devoted to something that is not a person is wrong. It robs all the other “persons” in your life of their humanity. You end up giving human dedication to something that is not human, thus making all the other people in your life less than human by subordinating them to an inanimate object.

And this, I think, is a very good way to understand the point our Lord is making. There are all kinds of things we need to fulfill our obligations to the people whom we love. One of them is money. You can’t feed a family or put a roof over their heads without it. But every month you’re handed that pay check, as abundant or as meager it may be, it isn’t the number of digits on the check that should give you satisfaction; it’s what that number should represent to the person who has his life well-ordered: the meeting of his responsibilities to those who depend on him.

The ancient Desert Fathers we remember as the supreme teachers of holiness. But in another sense we have to recognize that, spiritually speaking, they took the easy way out. By forsaking all material possessions and retreating into the solitude of the desert, they isolated themselves from everything that could possibly come between God and themselves.  We don’t have that luxury. We depend on others and others depend on us: in marriage, in the priesthood, in any number of situations in which we may find ourselves. They were like alcoholics who completely gave up drink; we are more like compulsive over-eaters who can’t give up food, but must try somehow to live with it in a modified and detached way—which, when you think about it, is a much more difficult thing. We don’t have that luxury. We depend on others and others depend on us: in marriage, in the priesthood, in any number of situations in which we may find ourselves. They were like alcoholics who completely gave up drink; we are more like compulsive over-eaters who can’t give up food, but must try somehow to live with it in a modified and detached way—which, when you think about it, is a much more difficult thing.

We can, therefore, presume that our Lord used the word that he used very deliberately. It isn’t a question of how much, but a question of why? When two people get married and look forward to a family, they’re concerned with creating a home and an environment in which a family can flourish. But as the years pass that focus can get lost. We can become so immersed in the various activities that keep the check coming in, that we can forget the reason for it all. Work and job, then, become goals in themselves; not that we consciously make them so, but that through years of going through the motions we have forgotten what it’s all for.

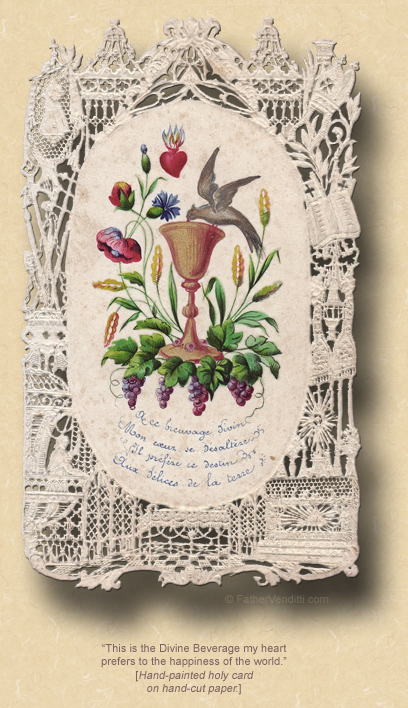

And this is true not only in reference to our families but most especially in reference to God. After all, just as material wealth exists for the benefit of our families, so our families are really nothing more than a means to bring ourselves and others closer to Christ. That’s why marriage is a sacrament: it is a way to God. One gets married precisely because two souls seeking perfection have a much better chance of success than one soul alone, because they temper each other, and limit each other, and motivate each other to do what is right. Otherwise, she exists only to please me, and I exist only to please her, when the reality should be that we both exist to help one another please God. And this is self-evident: how many people are there who would not be practicing their Catholic Faith at all except for the fact that, somewhere along the line, they married someone who went to church on Sunday? How many Catholic couples are there who honestly know that they would have given their faith a second thought were it not for the fact that they needed a baby baptized, or felt guilty about not raising a child in a religious environment. And while some might question the purity of such motives, the fact is that it’s exactly this sort of thing that marriage and family are for.

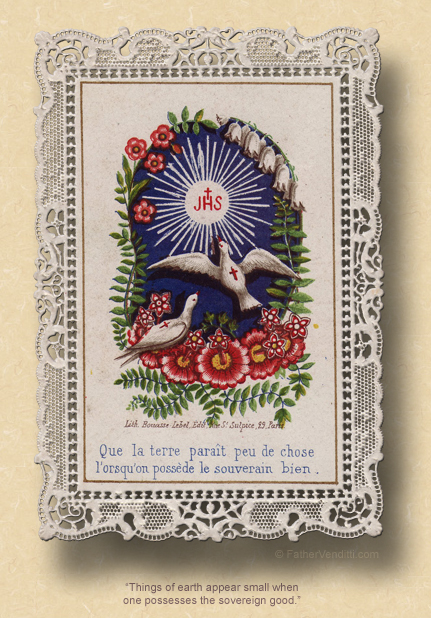

The longer I live the more I’m convinced that everything we do has some kind of ulterior motive, but that’s OK just so long as that ulterior motive is a positive one, and not mammon. In the end, no matter what we do, no matter what reason we think we have for doing it, it must be something that will lead us to God. And it will be, as long as it’s not mammon, as long as we can see the will of God in every task of life. And that happens when we train ourselves to see, in everyone who depends on us, the face of Christ.

* Almost all liturgical traditions observe a pre-Lenten season, with the sole exception of the ordinary form of the Roman Rite.

The extraordinary form of the Roman Rite observes a pre-Lenten period lasting for three weeks, known as the Septuagesima Season, consisting of Septuagesima, Sexagesima and Quinquagesima. In English speaking countries, this season is sometimes called “Shrovetide,” because it ends on the day before Ash Wednesday, which is often called “Shove Tuesday.”

The Churches of the Byzantine Rite observe a pre-Lenten season known as the Triodion, lasting for four weeks; it is sometimes preceded by a Sunday “before the Triodion,” as determined by the date of Easter. The first few Sundays of this season are thematic, taken from the Gospel of the day, from which each Sunday gets it’s name. The Sunday before the Triodion is known as the Sunday of Zacchaeus, the First Sunday that of the Publican and Pharisee, and the Second that of the Prodigal Son. The last two Sundays are named after the specific food items which may be eaten during the weekdays prior to them, as the fasting discipline of Lent is gradually imposed: the Sunday of Meatfare and the Sunday of Cheesefare. The day following Cheesefare Sunday is the First Day of the Great Fast, there being no tradition of an "Ash Wednesday."

A pre-Lenten season is also preserved in some of the more traditional branches of the Anglican and Lutheran communions, making the ordinary form of the Roman Rite the only major liturgical Tradition to have completely eliminated it; ironic since the liturgical reforms following the Second Vatican Council were said to have been done for largely ecumenical reasons.

|