Not "Be Careful What You Ask For" but "Be Careful How You Ask."

The Second Thursday of Lent.*

Lessons from the feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

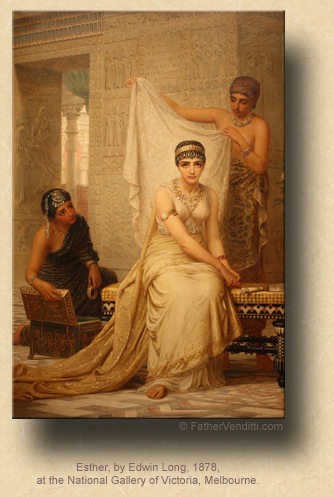

• Esther C: 12, 14-16, 23-25 (cf. Esther 4: 17 or Esther 14).**

• Psalm 138: 1-3, 7-8.

• Matthew 7: 7-12.

Lessons from the feria, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ezchiel 18: 1-9.

• Psalm 16: 8, 2.

• Matthew 15: 21-28.

The Second Thursday of the Great Fast; the Feast of Our Holy Father Porphyrius, Bishop of Gaza; and, the Feast of the Holy Great Martyr Photina the Samaritan.***

[There is no Divine Liturgy today in the Byzantine-Ruthenian Rite.]

FatherVenditti.com

|

1:53 PM 2/26/2015 — We all know that there are different kinds of prayer: the prayer of praise, the prayer of thanksgiving, the prayer of sorrow or contrition, the prayer of the presence of God; but, the first kind of prayer we learn as children is the one we all end up dong the most: the prayer of petition. It is a simple fact: most of the time, when we pray, we are asking for something. “Blessed us, O Lord, and these, Thy gifts…”; we are asking for something. “Now I lay be down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep…”; we are asking for something. “Lord, have mercy…”; we are asking for something. When His disciples asked Him to teach them how to pray, He taught them a prayer of petition: “...Give us this day our daily bread…” 1:53 PM 2/26/2015 — We all know that there are different kinds of prayer: the prayer of praise, the prayer of thanksgiving, the prayer of sorrow or contrition, the prayer of the presence of God; but, the first kind of prayer we learn as children is the one we all end up dong the most: the prayer of petition. It is a simple fact: most of the time, when we pray, we are asking for something. “Blessed us, O Lord, and these, Thy gifts…”; we are asking for something. “Now I lay be down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep…”; we are asking for something. “Lord, have mercy…”; we are asking for something. When His disciples asked Him to teach them how to pray, He taught them a prayer of petition: “...Give us this day our daily bread…”

The Scripture lessons for today's Mass are all about it. Queen Esther, in our first lesson, prays, “Lord, our King…befriend a lonely heart that can find help nowhere but in thee” (Es. 14: 3 Knox); and, in the Holy Gospel, our Lord instructs us that the prayer of petition, when offered in sincerity of heart, will not be refused by God, with the understanding, of course, that God might have another plan for us.

Let's face it: we spend a good part of our lives asking for things from people who have more than we have. We ask because we are in need. Sometimes, with some people, asking for something is the only contact we have with them, which doesn't make for a very reciprocal relationship; and, whenever we find ourselves on the receiving end of this kind of relationship, we find it a bit trying. Our children are always asking us for things, but we expect it from children. With other adults, it can try our patience; and, how many of us have had to tell someone—or perhaps we never got up the nerve but wanted to tell them—that it's rather annoying to be in a relationship where one is always being asked to give but never to receive?

We may have experienced that kind of frustration many times, but somehow we don't make the logical connection to our relationship with God; so, our Lord makes the connection for us: “Which one of you would hand his son a stone when he asked for a loaf of bread, or a snake when he asked for a fish?” (Matthew 7: 9-10 NABRE). It's a ridiculous comparison, of course, but our Lord is being ridiculous to make a point: we may get frustrated with people who are constantly asking us for something, always making demands on our time or our wallets or even just our emotional strength; but, God never gets tired of it. All the more reason for us to not forget that we owe a different kind of relationship to God. I think that may be the hidden meaning of our Lord's words at the end of today's lesson: “Do to others whatever you would have them do to you” (v. 12 NABRE). It's not just a repeat of the Golden Rule;—well, actually, it is—but it's more than that: He's saying: Just as you try to give your children whatever they ask, so God wants to give you whatever you ask; but, if you find that kind of one-sided relationship less than satisfying when you're the one being constantly asked, why do you presume to impose it on God?

That's not to say—as I'm sure you understand—that God would ever become impatient with us the way we do when someone is always making demands on us; but, the soul seeking after perfection should want a different kind of relationship with God: one that not only asks, but rejoices in whatever is received, and gives in return. And while it's always risky to presume what's in the Mind of our Blessed Lord and try to read Him between the lines, it seems that Holy Mother Church agrees with me; otherwise, why throw Psalm 138 right in between these two lessons today? And those of you who frequent Mass in the extraordinary form should know today's Psalm by heart:

Confitebor tibi, Domine, in toto corde meo,

quoniam audisti verba oris mei.

In conspectu angelorum psallam tibi;

adorabo ad templum sanctum tuum,

et confitebor nomini tuo…

I will give thanks to you, O Lord, with all my heart,

for you have heard the words of my mouth;

in the presence of the angels I will sing your praise;

I will worship at your holy temple

and give thanks to your name (vs. 1-2).

Certainly a large part of our relationship with God is shaped by our petitions—what we ask Him for—but I tend to suspect that the real indicator of how close we are to Him is shown by what we thank Him for. In fact, I don't wonder if one of the reasons we sometimes feel that our prayers go unanswered is because our prayers of petition aren't accompanied by a spirit of gratitude for what we've already received. Perhaps a good item to add to our examination of conscience during this Holy Season is a little daily inventory of the ratio between what we ask of God and what we thank Him for. St. John Vianney said, “God has never denied, and never will deny, anything to those who ask for his graces in the right way.”†

* The Second Thursday of Lent is what the Missal refers to as "Thursday of the First Week of Lent." Cf. the note regarding the designation of days during Lent, found here.

** The first lesson in the ordinary form is taken from the deuterocanonical sections of the Book of Esther—included in what the Protestants call the Apocrypha—and the citation as given here reflects the peculiar numbering system that the New American Bible Revised Edition has invented to include those chapters within the narrative of the canonical sections of the Book. Older Catholic Bibles, following the order of the Vulgate, will number these verses in a more conventional way: in this case, the passage is to be found scattered within Esther chapter 14 as found in Msgr. Knox's translation and Catholic Bibles preceding it, but it is not possible to give exact citations due to the fact that the NABRE has rearranged the verses based on the editors' assessment of how they fit into the narrative of the book as a whole. While it is true that the arrangement employed by the NABRE, used in the Roman Missal Third Edition, makes these verses comprehensible within the context of the rest of the book, it makes them practically impossible to find in older Bibles, and one finds oneself wishing some footnote could have been provided to supply for this deficiency. Adding to the confusion is the fact that not every modern Bible attempts to insert the verses in question into the narrative in the same way: e.g., the Jerusalem Bible extends v. 17 of chapter 4 into one, very long verse, but also gives it an alternate designation as ch. 5.

On the other hand, while older Catholic Bibles which follow the Vulgate all agree on where the deuterocanonical verses are to be found, their meaning is obscured because their insertion into the Vulgate was artificial and not based on the best scholarship. In short, the lesson as presented in the Missal is proprietary to the NABRE, and cannot be read at home except from that particular translation or from a Missal; unfortunate for those who do not find the NABRE to be the best translation of Holy Writ.

The Protestants reject the canonicity of these verses, and do not include them at all in their Bibles.

*** Photina is the name given by some Eastern Churches to the woman our Lord meets at the well in Samaria in John 4: 5-41. Neither her name, nor her post-conversion history, can be determined with certainty. Sometimes called Svetlana in the Slavonic Churches, she is commemorated by a few Eastern Churches on March 20th, along with her sons Victor (Photinos) and Josiah, and their sisters Anatolia, Photo, Photida, Paraskeva, Kyrakia and Domnina.

As usual in these cases, there is little actual evidence to substantiate the legends on which the feast is based, and the fact that all Photina's offspring seem to have Slovak names, while she herself is clearly a Samaritan, would tend to indicate that the legends originated in Eastern Europe.

These legends posit that Photina lived in Carthage with her younger son, Josiah, fearlessly preaching the Gospel there, while her older son, Victor, fought against the barbarians as a member of the Roman Legion before being appointed military commander of Attalia in Asia Minor. The story of the family's persecution by the emperor Nero is long and detailed,—much too detailed for the time in which the events supposedly took place—culminating in the entire family being martyred, with Photina herself being, ironically, thrown down a well sometime around the year AD 66.

† Curé d' Ars, Sermon on Prayer.

|