The Substance of Our Hopes.

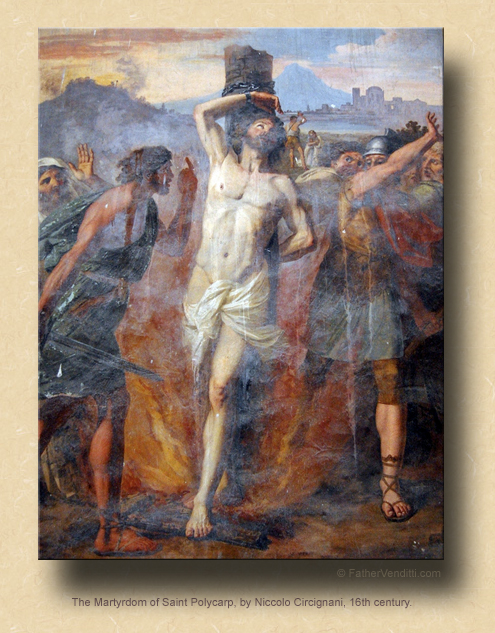

The Memorial of Saint Polycarp, Bishop & Martyr.

Lessons from the primary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Hebrews 11: 1-7.

• Psalm 12: 2-5, 7-8.

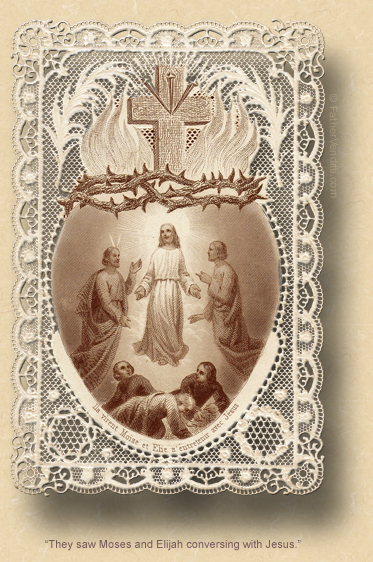

• Mark 9: 2-13.

|

…or, from the proper:

• Revelation 2: 8-11.

• Psalm 32: 3-4, 6, 8, 16-17.

• John 15: 18-21.

…or, any lessons from the common of Martyrs for One Martyr, or the common of Pastors for a Bishop.

|

The Third Class Feast of Saint Peter Damian, Bishop, Confessor & Doctor of the Church.*

Lessons from the common "In médio…" for a Doctor of the Church, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• II Timothy 4: 1-8.

• [Gradual] Psalm 36: 30-31.

• [Tract] Psalm 111: 1-3.

• Matthew 5: 13-19.

FatherVenditti.com

|

3:55 PM 2/23/2019 — Saint Polycarp has the distinction of being one of the very first martyrs venerated by the Church. He's one of a handful of early Fathers of the Church who testifies to the existence of a version of Matthew's Gospel in the Aramaic language less than sixty years after the Ascension of our Lord, far earlier than many modern Scripture scholars are willing to admit. He even quotes from it, throwing cold water on the presumption of the last fifty years that Mark's Gospel had to be written first simply because it's the shortest. He was a close friend of Saint John the Evangelist, and was consecrated Bishop of Smyrna by him, but was also personally known to almost all the Apostles. He went to Rome during the reign of Pope Anicetus, and was instrumental in helping to determine the date for Easter. 3:55 PM 2/23/2019 — Saint Polycarp has the distinction of being one of the very first martyrs venerated by the Church. He's one of a handful of early Fathers of the Church who testifies to the existence of a version of Matthew's Gospel in the Aramaic language less than sixty years after the Ascension of our Lord, far earlier than many modern Scripture scholars are willing to admit. He even quotes from it, throwing cold water on the presumption of the last fifty years that Mark's Gospel had to be written first simply because it's the shortest. He was a close friend of Saint John the Evangelist, and was consecrated Bishop of Smyrna by him, but was also personally known to almost all the Apostles. He went to Rome during the reign of Pope Anicetus, and was instrumental in helping to determine the date for Easter.

The Roman Breviary tells a cute story about him: while he was in Rome, he was also instrumental in bringing back to the faith a lot of people who had been drawn away from it by the heretics Marcion and Valentinus. They were Gnostics who, following the philosophy of Plato, posited a kind of dualism in God, and pretty much rejected the whole of the Old Testament as having nothing to do with Christ. So, one day Polycarp is walking down the street minding his own business and happens to bump into Marcion crossing the street; they had never met face to face, and Marcion asks, “Do you know who I am?” And Polycarp replies, “Yes, I know the first born of the devil!”

That's actually a good image of him, because he was known to have a fierce temper, but only when the faith was being challenged.  His temper turned out to be his undoing: he was so plain spoken and fearless in the face of heresy that he quickly ran afoul of the Emperor Nero, who had him burned at the stake and, as I said, was one of the first of the early Christian martyrs to be venerated. His temper turned out to be his undoing: he was so plain spoken and fearless in the face of heresy that he quickly ran afoul of the Emperor Nero, who had him burned at the stake and, as I said, was one of the first of the early Christian martyrs to be venerated.

As you know, our first lessons of late have been from the Book of Genesis, beginning with the creation, then continuing through all the events immediately afterward: the expulsion from the Garden of Eden, the murder of Abel by Cain, Noah and the flood, the story of the Tower of Babel. And all of a sudden, today, our first lesson is taken from the Epistle to the Hebrews as a kind of summation of everything we’ve been hearing, serving as a kind of moral to the saga. All of these Old Testament events are summarized for us as a lesson on the virtue of faith. Abel’s sacrifice was pleasing to God because of his faith; Enoch was taken up to heaven as a reward for his faith; Noah had enough faith to trust in the word of God transmitted to him, and built the ark to save him and his family. So, Hebrews frames the whole Genesis account in the context of faith.

Our first lesson, then, begins with what is probably the shortest yet most beautiful definition of Faith in the Bible: “What is faith? It is that which gives substance to our hopes, which convinces us of things we cannot see” (11: 1 Knox).** It’s what we mean whenever we use the term “leap of faith.” And that, in itself, is a meditation. We all have hopes and dreams, and our Lord, through the author of Hebrews, is telling us that these hopes and dreams become real through faith.

Sometimes our hopes and dreams are hard for us to maintain, simply because they are just hopes and dreams; and, hopes and dreams, so a person without faith would maintain, are not real. But it’s through faith that something that begins existence in our hearts can actually take on substance and change the whole of our lives. Hebrews reminds us of these Old Testament figures as a kind of proof that hopes and dreams can be real if our faith is strong enough; after all, what happened to the ancients actually happened.

That’s the whole point of the Missal pairing this lesson with Mark’s account of our Lord’s Transfiguration on Mount Tabor. Peter, James and John were our Lord’s closest friends, but He knew that even they—who had more faith than all the others—still had their doubts.  That’s why He let them see the Transfiguration, in much the same way that God rewarded the blind faith of those Old Testament figures. But bear in mind that, in both cases, these rewards for faith did not solve all their problems for them. Abel was still killed by his brother, Noah still had to build the ark, and—in case it had escaped our notice before—Peter, James and John, our Lord’s must trusted disciples, were the very same three whom our Lord chose to be with Him during His Agony in the Garden, and had to witness His passion and death. That’s why He let them see the Transfiguration, in much the same way that God rewarded the blind faith of those Old Testament figures. But bear in mind that, in both cases, these rewards for faith did not solve all their problems for them. Abel was still killed by his brother, Noah still had to build the ark, and—in case it had escaped our notice before—Peter, James and John, our Lord’s must trusted disciples, were the very same three whom our Lord chose to be with Him during His Agony in the Garden, and had to witness His passion and death.

So it would be trite to suggest that faith is some kind of magic bullet in times of trouble, because it isn’t. And yet, it’s faith that reminds us, if only like a faint whisper in our ear, that our Lord is there, and has not left us to twist in the wind. We all go up and down: sometimes our faith is strong, sometimes it’s very weak, most of the time it’s somewhere in between. But our Lord is always there even when we don’t sense Him there. If we make the mistake of equating the presence of God in our lives with some sort of emotional experience, that’s when faith starts to break down, because faith is not an emotion, nor is our Lord’s presence indicated by some sort of feeling. That’s all the result of the therapeutic approach to religion which is so common today. Faith is an act of the will, and acts of the will can be easy when we feel like it, and not so easy when we don’t.

Peter, James and John were all too pleased to have been given the grace to see our Lord in His heavenly glory on Mount Tabor; I doubt they were all that enthused to be on the Mount of Olives. But, they were still there, because they had faith. That faith didn’t spare them from sharing in our Lord’s sufferings, but it did give them the strength to persevere. And when the passion was over, what they had hoped for became real when they could be with our Lord again in His resurrected body. And so it will be for us, if only we can muster the will to keep faith, the substance of our hopes, and the reality of what we cannot see.

* Peter Damian (1001-1072) was a Benedictine Monk who wrote many important works on the liturgy as well as on theology and morals. Appointed Bishop of Ostia on account of his learning and high virtues, he become immensely helpful to Pope St. Gregory VII in his struggle for the rights of the Church. He retired to his abbey of Fonte Avellano where he died. In the ordinary form, his feast was on Feb. 21st.

** Ἔστιν δὲ πίστις ἐλπιζομένων ὑπόστασις, πραγμάτων ἔλεγχος οὐ βλεπομένων. Literally: “Now faith is that of which [is] being hoped, [the] reality of things the proof [of which] not being seen.”

|