No, It's Not the Feast of a Piece of Furniture.

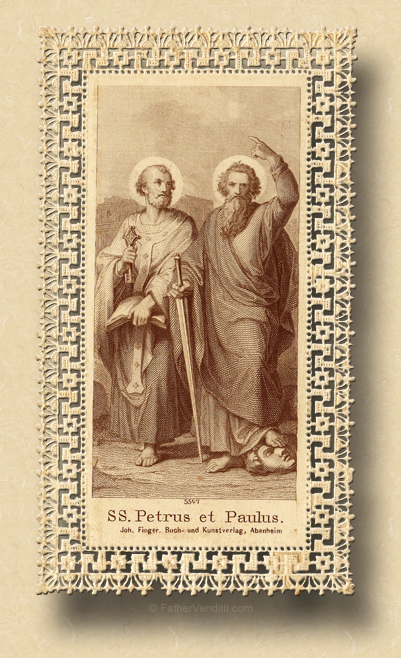

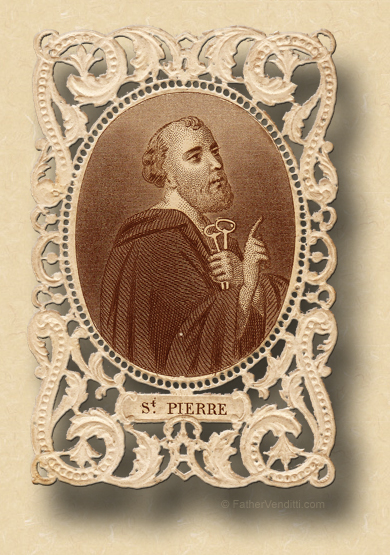

The Feast of the Chair of Saint Peter the Apostle.

Lessons from the proper, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Peter 5: 1-4.

• Psalm 22 (23).

• Matthew 16: 13-19.

The Second Class Feast of the Chair of Saint Peter;* the Commemoration of Saint Paul, Apostle; and, the Commemoration of the Second Monday of Lent.

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Peter 1: 1-7.

• Psalm 106: 32, 31.

• Matthew 16: 18-19 (replacing the psalm as the Tract).

• Matthew 16: 13-19.

The Third Monday of the Great Fast;** and, the Feast of the Venerable Relics of the Martyrs at Eugenia.

Lesson for the Sixth Hour with Holy Communion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:***

• Isaiah 8: 13—9: 6.

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:55 AM 2/22/2016 — No, the Feast of the Chair of Saint Peter does not celebrate a piece of furniture; nor is the chair in the title a papal throne making it a celebration of Papal authority. The feast was first celebrated in the fourth century, but has its roots much earlier than that in the common Roman custom of commemorating dead relatives and friends with an empty chair at table. In fact, pagan Rome observed an annual, ten day event between the thirteenth and the twenty-second of February in which every Roman household was expected to do this. After Christianity, the Romans started to remember some of the martyrs this way; but, since the date of the Blessed Apostle Peter's death is unknown, it was assigned to the last day of the observance, the twenty-second, as a way of wrapping it up. And that's how we get this feast of a Chair of Saint Peter. 9:55 AM 2/22/2016 — No, the Feast of the Chair of Saint Peter does not celebrate a piece of furniture; nor is the chair in the title a papal throne making it a celebration of Papal authority. The feast was first celebrated in the fourth century, but has its roots much earlier than that in the common Roman custom of commemorating dead relatives and friends with an empty chair at table. In fact, pagan Rome observed an annual, ten day event between the thirteenth and the twenty-second of February in which every Roman household was expected to do this. After Christianity, the Romans started to remember some of the martyrs this way; but, since the date of the Blessed Apostle Peter's death is unknown, it was assigned to the last day of the observance, the twenty-second, as a way of wrapping it up. And that's how we get this feast of a Chair of Saint Peter.

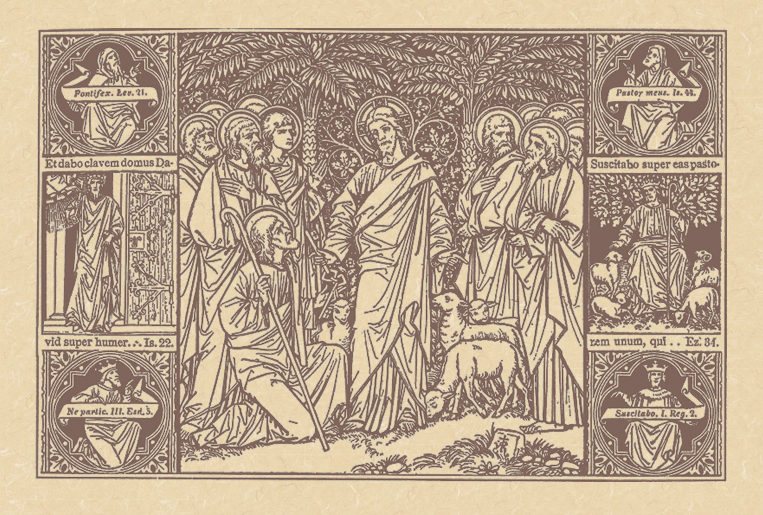

That's not to say that the authority of the Vicar of Christ is not referenced in the feast at all: it certainly is, particularly in the first lesson from the Prince of the Apostles' first epistle in which he instructs other bishops on how to shepherd their flocks; the Psalm, too, is an allegorical hymn to Christ the Good Shepherd, reminding us that the authority of the Pope—and any bishop for that matter—comes from Christ Himself, and is exercised primarily to console and nourish the hearts and souls of the faithful with sound teaching.

And the Gospel lesson shows our Blessed Lord setting the example, as it presents to us our Savior as the quintessential Teacher; and, today's class at the apostolic seminary happens to be on the dual subjects of Christology—the study of the two natures in Christ—and ecclesiology—the study of the Church. But, like any good teacher, our Lord doesn't just come out and say it; he plays Socrates, and teaches by asking questions; in this case, the quintessential question with which every Christian is confronted at some point in his or her life: “Who do you say that I am?” (Matt. 16: 15 NABRE). But it's interesting to note how he does this: He begins the process of teaching not by asking His disciples who they think He is, but who other people think He is. Two thousand years before psychology was invented, our Lord is a psychologist: He knows that, when you confront someone directly and ask them bluntly what they think, they're going to be defensive and throw up a wall and evade the question; so, He asks them not who they think He is, but “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” (v. 13 NABRE). By taking them out of the equation, He prevents them from becoming defensive because He's not asking them about themselves. Not having anything to be defensive about, they feel free to say whatever is on their minds, so they give Him a whole catalog of answers: “Some say John the Baptist, others Elijah, still others Jeremiah or one of the prophets” (v. 14 NABRE). But He's not done: now that He's got their defenses down and in a talkative mood, He confronts them with the personal question: “Jesus said to them, 'And what of you? Who do you say that I am?'” (v. 15 Knox).

Think back to your school days: Sister is in a particularly surly mood. She's firing out questions, ruler in her hand, and woe betide your knuckles if she calls on you and you get the answer wrong. But there's always that one annoying kid in the room who thinks he knows everything, who is always the first to shoot his hand up in the air, and whom Sister thinks is the greatest thing since sliced fruitcake. You hate his guts, but on an occasion like this he has his uses; so, you all look at him as if to say, “You handle this one.” So the disciples all look at Simon. Why Simon? He's the favorite. True to form, glorying in the moment, Simon answers the question, and naturally gives the right answer: “Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God” (v. 16 Knox).  And the Gospel goes on to show us what most everyone regards as the meat of this Gospel lesson: our Lord rewards Simon with the gold star of changing his name to Peter, which means “Rock,” appointing him Prince of the Apostles and head of the Church, and giving to him the metaphorical keys to the kingdom of heaven, providing the Scriptural basis for Papal Infallibility. All well and good. Long live the Pope! And the Gospel goes on to show us what most everyone regards as the meat of this Gospel lesson: our Lord rewards Simon with the gold star of changing his name to Peter, which means “Rock,” appointing him Prince of the Apostles and head of the Church, and giving to him the metaphorical keys to the kingdom of heaven, providing the Scriptural basis for Papal Infallibility. All well and good. Long live the Pope!

But, there's more to this lesson than a Biblical defense of the Papacy; equally important is the question asked by our Lord. Jesus isn't just asking Peter; He's asking all of us: “Who do you say that I am?” And all of us are going to have to figure out how we're going to answer that question, because the consequences of giving the wrong answer are a lot more serious than a ruler to the knuckles. Those who cling to a purely secular and social interpretation of the Gospel would see Jesus as a social and political teacher who inspires us to be concerned for the poor and the downtrodden and the oppressed; but I doubt they would see him as any kind of god to whom is owed worship and some form of personal, moral commitment. By contrast, in a previous life I once had a Buddhist coworker who saw in Jesus a spiritual guru with great mystical teachings to impart, but with no understanding of Jesus having any kind of message beyond being at peace with ourselves. The bottom line is: we do not have a right to invent Jesus Christ: He is who He is regardless of what any of us think of him.

Three thousand years before God became a man in the person of Jesus Christ, God and man had the first really meaningful conversation with one another since Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden: Moses approached the burning bush and asked, “Who are you?” And what were God’s first words to man? “I am Who I am!” (Exodus 3: 14). And God has never changed his identification of Himself. When He appeared to Jeremiah the Prophet, He said, “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you” (Jer. 1: 5). When the Man Born Blind asked Him where he could find the Messiah, Jesus said, “I who speak to you am he” (John 4: 26). When Jesus spoke to Saul on the road to Damascus, Saul asks, “Who are you, Lord?”; and God’s response: “I am He whom you are persecuting” (Acts 9: 5). The Epistle to the Hebrews: “Jesus Christ: yesterday, today and the same, forever” (Heb. 13: 8). We do not define Christ. He defines us.

As for those who still choose to make up Jesus for themselves to suit their own agendas, Saint John probably said it best:

He, through whom the world was made, was in the world, and the world treated him as a stranger. He came to what was his own, and they who were his own gave him no welcome. But all those who did welcome him, he empowered to become the children of God, all those who believe in his name (John 1: 10-12 Knox).

And if you're still searching for some theme to guide your Lenten meditations, you might consider this: ask yourself not “Who is Jesus to me?” but “Who am I to Jesus?” Are you Cain, being asked by God, “Where is your brother?” (Gen. 4: 9). Are you Elijah, looking for God in the magnificence of nature, and missing him standing right there next to you in “the whisper of a gentle breeze” (1 Kings 19: 12)? Are you Judas, looking for Jesus to impose global justice and equality and solve the world’s problems, finding yourself frustrated because He keeps talking about spiritual things? Are you Peter, looking for God to save you as you sink into the sea? Are you Nathaniel, who, when he first meets Jesus, doesn’t know who He is, but only knows that He is something different?

The first step is to let Jesus define Himself. The next step is to then let Jesus define us.

* Originally, this feast commemorated Saint Peter's Chair in Antioch, with the Apostles' Roman chair commemorated on Feb. 18th. In the Missal of Saint John XXIII, the two feasts were combined on this day.

** Because the Great Fast began on the Monday after Cheesefare Sunday, today is the Third Monday of the season, not the second.

*** In the Byzantine Tradition—as in most Eastern Christian traditions, both Orthodox and Catholic—the Eucharist is not celebrated on the weekdays of the Great Fast. In some traditions, the faithful are expected to fast from the Blessed Eucharist during this time, abstaining from Holy Communion except on Saturdays and Sundays.

In other traditions, including the Ruthenian recension, Holy Communion may be distributed to the faithful daily provided that the Divine Liturgy is not celebrated. On Wednesday and Friday evenings, the Divine Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts is celebrated, consisting of a form of Solemn Vespers coupled with a Communion Service in which the Eucharist confected on the previous Sunday may be received by the faithful. On the other weekdays, another service—usually the Sixth Hour of the Divine Office or a simpler service called "Typica"—may be celebrated at which Holy Communion may also be offered to the faithful. Notice that the readings for these services do not include a Gospel lesson; a Gospel would only be sung on significant Holy Days or during the Presanctified Liturgies of Holy and Great Week.

|