Original Sin: it's not just for kids anymore.Rom. 13:11b-14:4:

Matt. 6:14-21. The Fourth Sunday of the Triodion, known as The Sunday of Cheesefare. The Holy Apostle Archippus.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

4:16 PM 2/21/2012 — I confess that today’s homily is the same that I have preached for every Cheesefare Sunday since I’ve been here. The day after Cheesefare is, as you know, the first day of the Great Fast; and I simply haven’t found a better way to say what needs to be said.

When I was younger, I had an inkling to try my hand at the monastic life. I had tried my hand at the seminary once and it didn’t work out, so I thought I would escape from it all into the seclusion of a Carthusian monastery. Now, the Carthusians, founded by St. Bruno in the 11th century in France, are probably the strictest order of monks in the world; and I went to their place in Vermont for a month long stay to look them over and let them look at me.  And one of the things I did while I was there was to read the rule of life that St. Bruno wrote for them in the year 1050. And it struck me that every aspect of that rule is focused on this idea that we are here to please God and no one else. And he even addresses the idea that we have to presume this about everyone else, not just ourselves. For example, there’s a passage in the rule where he says that if you observe a brother doing something you were told was wrong, whatever it may be—whether it’s conversing with a woman, or entering a shop, or eating something forbidden on a fast day, or doing anything that is ordinarily forbidden—always assume he has permission; this way, you will never sin by judging another unjustly. And one of the things I did while I was there was to read the rule of life that St. Bruno wrote for them in the year 1050. And it struck me that every aspect of that rule is focused on this idea that we are here to please God and no one else. And he even addresses the idea that we have to presume this about everyone else, not just ourselves. For example, there’s a passage in the rule where he says that if you observe a brother doing something you were told was wrong, whatever it may be—whether it’s conversing with a woman, or entering a shop, or eating something forbidden on a fast day, or doing anything that is ordinarily forbidden—always assume he has permission; this way, you will never sin by judging another unjustly.

I never forgot that, and have often speculated how much anxiety we could eliminate from our lives if we could only find a way to live that principle in all our lives. Of course, we have no control over the spiritual lives of others;—except perhaps by example—but we do have control over our own; but even that can be a hard sell, sometimes. How often have we heard a sermon or read something that strikes a chord in us, and our first thought is to apply it to someone else? How many times have we heard the priest say something about how to behave and the first thing that pops into our heads is, “I sure hope so-and-so heard that”?

This principle of doing the right thing to please God and not caring whether anyone else understands—or even if they misunderstand—is addressed very directly in that section of St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans we just heard; but it is also presented to us in today’s Gospel in a veiled way—in a way that requires us to look deeply into the meaning of our Lord’s words. He says, "When you fast, do not look dismal, like the hypocrites, for they disfigure their faces that their fasting may be seen by others. Truly, I say to you, they have received their reward. But when you fast, anoint your head and wash your face, that your fasting may not be seen by men but by your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you" (Matthew 6:16,17). What St. Bruno understood, and what we have to understand as well, is that by fasting our Lord is not simply speaking of abstaining from food for spiritual reasons; fasting here is interpreted as anything that we do that pleases God, even if it is not understood by anyone else. And when we realize that, all of a sudden we see that this has not to do simply with personal acts of mortification, like giving up food, but with everything that touches on our relationship with God and with one another. A person who consistently does what is right in his daily life will end up disappointing more people than he pleases, if he is truly doing what is right. Sometimes we make the mistake of thinking that what is pleasing to others is what is right; and that’s almost never the case. If it were, life would be a breeze; but we know it isn’t.

And that is, in fact, the reason that this Sunday, Cheesefare Sunday, is sometimes referred to as the Sunday of Forgiveness; for on this Sunday we are seeking forgiveness, not just from God, but also from one another. Because if we are true to the spirit of Lent, and make a serious effort to live the Gospel of Jesus Christ in those areas where we had not been before, we’re going to be disappointing someone somewhere, because we will be living to please God and not each other. So we begin Lent by recognizing that those around us will no longer be existing to make us happy; that not only should we now start to do what is pleasing to God, but that we should give the other people in our lives the freedom to do the same, and stop expecting everything they do to meet with our approval.

It is a twisted fact of human nature that the people who set the highest standards for themselves are the most miserable because no one around them lives up to their expectations. And it’s not simply a matter of excepting the failures of others—that’s too easy a rationalization—because it may not be a failure at all: the standards by which we think everyone should live may not apply to someone else because we don’t know the circumstances of that person’s life. Even if we were to completely eliminate personal sin from our lives, it would mean nothing if we still stood in judgment over someone else, or allowed someone else to be held accountable for making us happy. It’s like our Lord says in the very first sentence of today’s Gospel: "If you do not forgive others their trespasses, neither will your heavenly Father forgive yours" (Matthew 6:15).

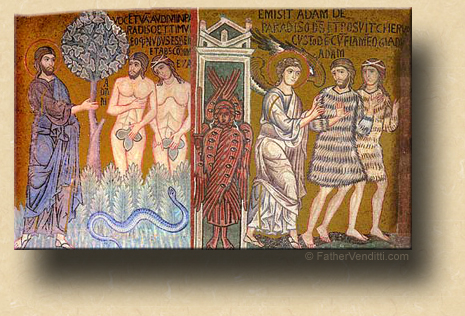

Now, that raises a question: does this not put us on the track of becoming moral relativists? After all, right and wrong are determined by God, not by us; so, how do we “forgive” (to use our Lord’s own word) someone who’s life or actions departs from the Gospel of Jesus Christ?  And here’s where the other Liturgical texts for this day are instructive. They focus us to contemplate God’s supreme act of judgment upon man: the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. The sin of Adam was the sin of wanting to be God, repeated in each one of us every time we set aside God’s law and decide for ourselves what’s right and wrong. That’s why it’s called the “Original Sin,” because all sin stems from it. And man paid a penalty, as the Book of Genesis tells us: our food and livelihood are no longer supplied by God, but by the sweat of our brow; the nakedness of our bodies ceases to be a thing of beauty and becomes a source of temptation; even the pain of a woman in childbirth, Genesis tells us, is the result of that one first sin. So terrible is that sin—usurping the authority of God and deciding for ourselves the difference between right and wrong—that its effects are passed on through every generation. And here’s where the other Liturgical texts for this day are instructive. They focus us to contemplate God’s supreme act of judgment upon man: the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. The sin of Adam was the sin of wanting to be God, repeated in each one of us every time we set aside God’s law and decide for ourselves what’s right and wrong. That’s why it’s called the “Original Sin,” because all sin stems from it. And man paid a penalty, as the Book of Genesis tells us: our food and livelihood are no longer supplied by God, but by the sweat of our brow; the nakedness of our bodies ceases to be a thing of beauty and becomes a source of temptation; even the pain of a woman in childbirth, Genesis tells us, is the result of that one first sin. So terrible is that sin—usurping the authority of God and deciding for ourselves the difference between right and wrong—that its effects are passed on through every generation.

And, yet, in spite of this, God still judged man worth saving: he loved his creation so much that, instead of allowing man to suffer the price for that sin, he became a man himself and suffered it for us. That’s why on the Sunday’s of the Great Fast we celebrate the Liturgy of St. Basil. We groan about it every year and tell each other it’s much too long; but its anaphora recounts the history of our salvation, from the fall of Adam to the Passion of Our Lord, reminding us that God, instead of simply forgiving us—which would have obfuscated the very concept of his justice—chose instead to become one of us and pay the penalty of death himself. If God has chosen to do that, then how can we continue to harbor ill thoughts against another whose wrong against us is so petty in comparison?

So, as we prepare for the beginning of the Great Fast, I would recommend the following exercise, which I seem to recommend every year and will continue to do so: count the number of people in your life that you will have nothing to do with—because they once did something to hurt you and never asked forgiveness, or because you don’t like their personality, or because they’re not living the way you think they should, or maybe because you just don’t like the looks of them—count them, and realize that that’s the extent to which you have made yourself unworthy of what God has done for you. And if, by the end of Lent, you can succeed in lowering that number, that’s the extent to which you have become more pleasing to God than you were before.

Father Michael Venditti

|