Too Many Chiefs and Not Enough Indians.

What to do about all the new movements and communities sprouting up in the Church today.

FatherVenditti.com

|

5:18 PM 2/20/2016 — Someone who took the time to answer my survey about this site expressed a desire for more “ordinary blog posts,” which I interpret to mean more non-homiletic articles; so, here's one.

Not long ago, I had made a remark to another priest that the Church would do well to place a moratorium on the establishment of new “movements” and religious communities. Since the pontificate of Saint John Paul II, it seems that everyone and his uncle feels inspired by God to be a founder of something or other; and, more often than not, it turns out to be something that pretends to be something Franciscan: the Franciscans of the Immaculate, the Franciscans of the Sacred Heart, the Franciscans of Renewal … my favorite is the Sisters of Saint Francis of the Martyr Saint George. I mean, they couldn't choose one? I love Saint Francis just as much as the next guy, but his rule is nothing unique. What's wrong with some of the other holy founders and their rules? Personally, I recognize only three branches of the Franciscan family: the brown-robed Order of Friars Minor, who believe themselves to be the community founded by Francis; the black-robed Order of Friars Minor Conventual, who actually are the community founded by Francis; and, the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, who never claimed to be founded by Francis. Not long ago, I had made a remark to another priest that the Church would do well to place a moratorium on the establishment of new “movements” and religious communities. Since the pontificate of Saint John Paul II, it seems that everyone and his uncle feels inspired by God to be a founder of something or other; and, more often than not, it turns out to be something that pretends to be something Franciscan: the Franciscans of the Immaculate, the Franciscans of the Sacred Heart, the Franciscans of Renewal … my favorite is the Sisters of Saint Francis of the Martyr Saint George. I mean, they couldn't choose one? I love Saint Francis just as much as the next guy, but his rule is nothing unique. What's wrong with some of the other holy founders and their rules? Personally, I recognize only three branches of the Franciscan family: the brown-robed Order of Friars Minor, who believe themselves to be the community founded by Francis; the black-robed Order of Friars Minor Conventual, who actually are the community founded by Francis; and, the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, who never claimed to be founded by Francis.

Then there's the never-ending procession of new movements and secular institutes, some clerical and some lay, all pushing the boundaries of established forms of consecrated and semi-consecrated life, many having good points to recommend them, but almost all running afoul of the Church at some point along the way. Take, for example, the Neo-Catechumenal Way (beware of anything with the prefix “neo”), of which many conservative types like me are enamored, but who seem to be particularly challenged when it comes to obeying liturgical regulations or respecting the spiritual authority of local parish priests. I was once stationed with a priest who belonged to one such institute and who had been assigned to my parish because of some loan program the diocese had with this group, and I had occasion to correct him one day on a point of liturgical propriety. “This is the custom in our community,” he said to me, as if my parish was part of his community, and as if his community had been given a dispensation to deviate from the Roman Missal. Wrong on both counts.

Hence, my remark to another priest that we really didn't need any more new ventures like this, and should concentrate instead on shoring up and reforming what already is … kind of analogous to what makes Beethoven a great composer: he was revolutionary without ever working outside already established musical forms. Anyone can be new and revolutionary by blowing up everything; only a genius can be creative and brilliant within the framework of what's already tried and true. He countered that, because the established communities had degenerated into such overt liberalism, some people feel those groups have nothing to offer them. It got me to thinking back to my own experience in religious life and the experiences of the many religious I've directed over the years, one of which actually attempted to start her own community.

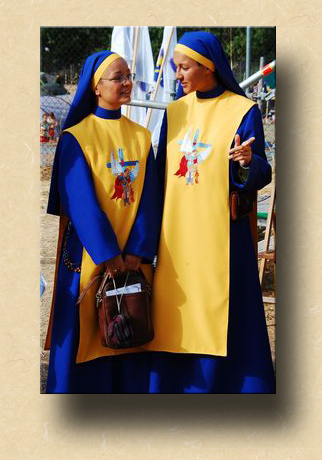

The problem, as I see it, is rooted—as most problems are—in the sin of pride. Everyone wants to be a chief and no one wants to be an Indian, though most of these could never comprehend that any kind of pride is involved. The one person referenced came out of a generation that was so traumatized by Vatican II that she could never trust the “official” Church; thus, when she launched out into the realm of becoming a “holy foundress,” she did it on her own … a less-than-genius-level priest got involved, and they were off and running. She quickly attracted some young girls, put them into a habit that she had designed herself—as gaudy as they come—and found a Catholic institution owned by similarly traumatized lay people to give them a house to live in and a ministry to perform. After some years, that Catholic institution sought to regularize itself within the Church via the local bishop; and, he, in turn, sought to regularize the makeshift nuns by constituting them an Association of the Faithful, the first step in becoming a religious community of diocesan rite. The fly in the ointment was that the “holy foundress” wasn't willing to accept any guidance: she was still traumatized, and viewed any attempt of the Church to “regulate” her activities as the action of the Devil seeking to destroy the true faith. The bishop had attempted to pursue the course that any prudent bishop seeks to pursue when establishing a community of diocesan rite, that is, solicit the services of an already established community of pontifical rite to guide and help form the new community, but the whole idea was rejected by the “holy foundress.”

Ultimately, the institution to which the makeshift community had attached itself became regularized in toto, becoming a Public Association of the Faithful under the auspices of the Pontifical Council for the Laity, which made the status of the makeshift community tenuous. They departed, and eventually died of attrition, the “holy foundress” going to her grave firmly convinced—like Jefferson Davis after the Civil War—in the justice of her cause.

Why she was unable to accept guidance is a complicated issue we need not explore here, but it's important to consider that her attitude is not uncommon. The sin of pride, like all sins, begins by masquerading as a virtue, usually the virtue of constancy or fortitude. No one, for example, denies that the organization Priests for Life does wonderful work, but is it necessary for the priest who founded it to be its director until the Second Coming? When his own bishop attempted to recall him to normal pastoral duties in his diocese—not because he was anti-life but because, like any good bishop, he knew the dangers to a priest who is allowed to carve his own niche for too long—he became entrenched, seeing any attempt to pressure him to turn over his apostolate to another priest as an attack on unborn children. Why she was unable to accept guidance is a complicated issue we need not explore here, but it's important to consider that her attitude is not uncommon. The sin of pride, like all sins, begins by masquerading as a virtue, usually the virtue of constancy or fortitude. No one, for example, denies that the organization Priests for Life does wonderful work, but is it necessary for the priest who founded it to be its director until the Second Coming? When his own bishop attempted to recall him to normal pastoral duties in his diocese—not because he was anti-life but because, like any good bishop, he knew the dangers to a priest who is allowed to carve his own niche for too long—he became entrenched, seeing any attempt to pressure him to turn over his apostolate to another priest as an attack on unborn children.

This whole idea could probably be expounded more thoughtfully, but let me get to the point: based on my own experience and that of those I've directed over the years, here's how I imagine an ideal program for the establishment of a new community should progress.

First, before considering whether someone is cut out to be the founder of a new community, it must be ascertained that he or she actually has a religious vocation; toward this end, the would-be founder should be required to apply to and be accepted into an already established religious community of pontifical rite, and persevere in that vocation through to solemn vows. At that point, he should then be permitted to meet with his superiors and the diocesan bishop in whose diocese he's seeking to begin his community. If everyone agrees that he's got the “stuff” that makes a founder—and his community is willing to provisionally release him—the bishop can give him a house and place him under the diocese's protection as an Association of the Faithful, with the condition that his original community will provide him with a provisional superior and a provisional formation director. It would be under their guidance that he would draft his new community's constitution, and new aspirants would be formed. Under no circumstances would he be permitted to do any of this on his own. Each year, the provincial council of the original community, in conjunction with the bishop, would evaluate their progress. At the point that the new community accrues a minimum of twenty members, and at least five years have past, can the original community make a recommendation to the bishop that they depart and that he consider raising the new group to the rank of a religious community of diocesan rite, with the further provision that the “founder” not be the first elected superior. For the next ten years thereafter, the original community would make an annual visitation to evaluate the new community's progress, making their report to the bishop. In the event that the community should fail or be dissolved, the members would have agreed previously to return to their founder's original community and accept whatever assignments are given to them there.

The advantages to this system should be obvious, the most important being that the would-be founder would really have to enjoy a high level of humility, which all of the Church's holy founders have always manifested. It's basically how Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross started the Discalced Carmelites. It's also how Venerable Teresa of Calcutta started the Missionaries of Charity.

One aspect of this plan, that I haven't mentioned, might be controversial: if the host bishop approves men to be ordained for the new community, they must be trained in the formation program of the guiding community and incardinated into it, not into the host diocese. The current practice of ordaining men for fledgling communities of diocesan rite, technically incardinating them into their host dioceses, is a mistake, resulting in men being funneled into the secular priesthood when the community fails who never aspired to that demanding vocation, nor possess the spiritual formation, psychological self-sufficiency and physical constitution necessary for it.

|