Septuagesima: It's Not Just for Traditionalists Anymore.

The Fifth Friday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the primary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Genesis 3: 1-8.

• Psalm 32: 1-2, 5-7.

• Mark 7: 31-37.

The Friday after Sexagesima.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:*

• II Corinthians 11: 19-33; 12: 1-9.

• Psalm 82: 19, 24.

• Luke 8: 4-15.

Cheesefare Friday; and, the Feast of Our Venerable Father Martinian.

[There is no Divine Liturgy today in the Byzantine-Ruthenian Rite.]**

FatherVenditti.com

|

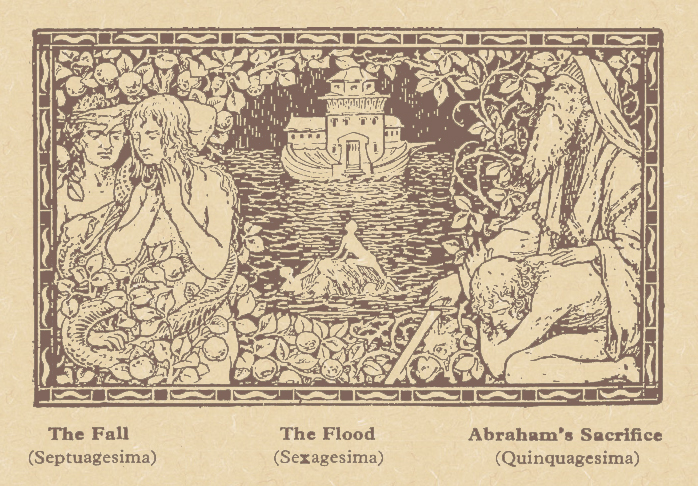

2:05 PM 2/13/2015 — For those of you who occasionally hear Mass in the extraordinary form, you would know that we are in the midst of what is traditionally known as the Septuagesima season, named after the first of the three Sundays that comprise it; the priest would already be wearing the purple of Lent, and we would already have replaced the Alleluia with another verse. In English speaking countries, this season was sometimes called “Shrovetide,” because it ends on the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday, which was often called “Shove Tuesday.” It's actually a universal practice, and is preserved to this day in every Christian Church that has a serious liturgical tradition, even the more traditional brands of the Anglican and Lutheran communions; in the Eastern Catholic Churches, in which I served for many years, as well as in the Orthodox Churches, it's called the Triodion. It was, of course, eliminated in the ordinary form of the Roman Rite during the reforms following the Second Vatican Council; and, if you go on the Internet, you'll find numerous articles by people wringing their hands over whether that was a good idea, especially since many of those reforms were supposed to be for ecumenical reasons. The best way, I think, to describe Septuagesima is as a preparation for the preparation: if Lent is supposed to prepare us for Easter, then Septuagesima is designed to prepare us for Lent.

Those of you who have no experience except with the liturgical tradition of the Latin Church after Vatican II may find it overkill to have a time of preparation for Lent itself; but, you must remember that, in centuries past, Lent was not just a time to prepare ourselves for Easter by giving up chocolate and saying a few extra prayers. When the Church was young—and the Apostles were still preaching the words of our Lord from memory—very few people were born into the faith; they joined the Church as adults. And joining the Church meant a big change in a person’s life, especially in an age of persecution. Lent was a time of intense study, prayer, fasting and personal purification. Baptism, after all, is the restoration of Sanctifying Grace, one should not take it lightly.

And, as in all things, the Church follows the example of our Lord Who, before beginning the work He came to do, fasted and prayed in the desert for forty days. He didn’t give up chocolate and television for forty days; He fasted and prayed for forty days. And so, the Church, following a tradition handed down from the Apostles, places great emphasis on this thing we call Lent, so much so that before we even enter into it we take time to prepare with two or three weeks, depending on the date of Easter, during which we gradually ease ourselves into a spirit of self-denial.

During the vacation from which I just returned, I had the chance to go swimming, but I had not been swimming for a long time, and the water seemed cold to me; so, instead of diving right in—if you can picture such an ungraceful thing—I walked into the water slowly, little by little, splashing myself in order to acclimate to the temperature of the water. That’s what we do during Septuagesima; we acclimate ourselves to, first, acknowledge that we are sinners and need to reform our lives, then we try to accustom ourselves to the notion that, in spite of our sinfulness, God really does want us to reform; and we begin, little by little, to impose upon ourselves that measure of self-denial that makes the reform of our lives possible in grace.

The Eastern Churches have an interesting custom: the two weeks before Lent begins are focused on specific objects for our self-denial: the week of Meatfare is the last week before Easter during which they eat meat, and the week of Cheesefare is the last week in which dairy products are eaten, and during Lent itself they eat neither; so, they take the idea of fasting during Lent very seriously indeed; and, the last Sunday before Lent, which is called Cheesefare Sunday, is also called the Sunday of Forgiveness, because it is presumed that, if one is focused on self-denial so thoroughly, one is going to be something of an annoyance to others, so the idea is that we forgive each other in advance for all the inconvenience that our practices of mortification will cause.

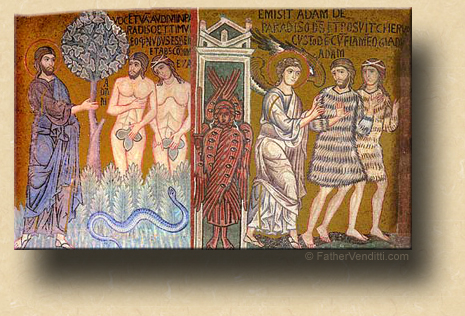

And here is where there is still something of this left in the ordinary form of the Roman Rite in which we celebrate here at the Shrine, even if we are still singing Alleluia and no longer calling it the Septuagesima season; for, the first lessons for Holy Mass in the first cycle are all being taken, in case you didn't notice, from the account of creation in the Book of Genesis, which figures prominently in the texts of the Divine Office used both in the Eastern Churches and in the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite. They focus us to contemplate God’s supreme act of judgment upon man: the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. What was the sin of Adam and Eve? It wasn't just eating an apple that, for totally arbitrary reasons, was forbidden to them; the fruit was from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and the act of eating it symbolizes the attempt to take away from God the power to decide good from evil and decide it for ourselves; in other words, the sin of Adam was the sin of wanting to be God, repeated in each one of us every time we set aside God’s law and decide for ourselves what’s right and wrong. That’s why it’s called the “Original Sin,” because all sin stems from it. And man paid a penalty, as the Book of Genesis tells us: our food and livelihood are no longer supplied by God, but by the sweat of our brow; the nakedness of our bodies ceases to be a thing of beauty and becomes a source of temptation; even the pain of a woman in childbirth, Genesis tells us, is the result of that one first sin. So terrible is that sin—usurping the authority of God and deciding for ourselves the difference between right and wrong—that its effects are passed on through every generation, which is why we are born in this state of original sin. And here is where there is still something of this left in the ordinary form of the Roman Rite in which we celebrate here at the Shrine, even if we are still singing Alleluia and no longer calling it the Septuagesima season; for, the first lessons for Holy Mass in the first cycle are all being taken, in case you didn't notice, from the account of creation in the Book of Genesis, which figures prominently in the texts of the Divine Office used both in the Eastern Churches and in the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite. They focus us to contemplate God’s supreme act of judgment upon man: the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. What was the sin of Adam and Eve? It wasn't just eating an apple that, for totally arbitrary reasons, was forbidden to them; the fruit was from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and the act of eating it symbolizes the attempt to take away from God the power to decide good from evil and decide it for ourselves; in other words, the sin of Adam was the sin of wanting to be God, repeated in each one of us every time we set aside God’s law and decide for ourselves what’s right and wrong. That’s why it’s called the “Original Sin,” because all sin stems from it. And man paid a penalty, as the Book of Genesis tells us: our food and livelihood are no longer supplied by God, but by the sweat of our brow; the nakedness of our bodies ceases to be a thing of beauty and becomes a source of temptation; even the pain of a woman in childbirth, Genesis tells us, is the result of that one first sin. So terrible is that sin—usurping the authority of God and deciding for ourselves the difference between right and wrong—that its effects are passed on through every generation, which is why we are born in this state of original sin.

And, yet, in spite of this, God still judged man worth saving: He loved his creation so much that, instead of allowing man to suffer the price for that sin, He became a man Himself and suffered it for us. That's another reason why the Sunday before Lent in the Eastern Churches is called the Sunday of Forgiveness, and from it we can take away a useful lesson: because instead of simply forgiving us—which would have obfuscated the very concept of His justice—God chose instead to become one of us and pay the penalty of death Himself. If God has chosen to do that, then how can we continue to harbor ill thoughts against another whose wrong against us is so petty in comparison?

So, as we prepare for the beginning of Lent, if we have not yet considered what exactly we're going to do for Lent, we might consider the following exercise: count the number of people in our lives that we will have nothing to do with—because they once did something to hurt us and never asked forgiveness, or because we don’t like their personality, or because they’re not living the way we think they should, or maybe because we just don’t like the looks of them—count them, and realize that that’s the extent to which we have made ourselves unworthy of what God has done for us. And if, by the end of Lent, we can succeed in lowering that number, that’s the extent to which we have become more pleasing to God than we were before.

* In the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, readings are not provided for each day; the lessons on ferial days are taken from the preceeding Sunday.

** During the pre-Lenten and Lenten seasons in the Byzantine-Ruthenian Rite, the Divine Liturgy is celebrated only on Saturdays and Sundays.

|