We Can't Follow the Lord on Our Own Terms.

The Fifth Thursday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the primary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Genesis 2: 18-25.

• Psalm 128: 1-5.

• Mark 7: 24-30.

The Third Class Feast of the Seven Holy Founders of the Servite Order, Confessors.

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ecclesiasticus 44: 1-15.

• Isaiah 65: 23 [in place of the Psalm].

• Matthew 19: 27-29.

Cheesefare Thursday; and, the Feast of Our Holy Father Melitius, Archbishop of Antioch.

Lessons from the triodion, according to the typicon of the Byzantine-Ruthenian Rite:

• Jude 11-25.

• Luke 23: 1-34, 44-56.

FatherVenditti.com

|

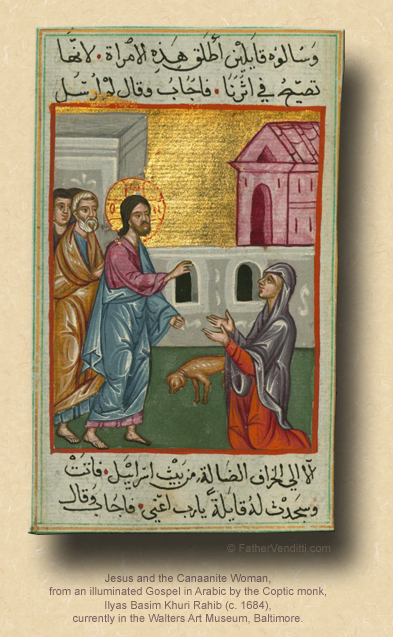

9:13 AM 2/12/2015 — Those of a purely elementary faith—those unpracticed in the movements of the soul through the interior life—would be very confused with today's Gospel lesson (in the ordinary form); for, in it, our Blessed Lord is approached by a woman who is drawn to him solely by faith, seeking nothing for herself, but begging him to help her tormented daughter. She's persistent, so much so that, in Matthew's account of this encounter, the disciples ask him to “Rid us of her..., she is following us with her cries” (Matt. 15: 23 Knox). He turns to her and says, “Let the children have their fill first; it is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs.” (Mark 7: 27 Knox); in other words, I'm not going to help you; you're not even a Jew. And I'm sure you're waiting with baited breath for me to explain to you how our Lord isn't really saying what he seems to be saying, and how this is all the result of some inferior translation, which, as you know, is something that I often like to do. 9:13 AM 2/12/2015 — Those of a purely elementary faith—those unpracticed in the movements of the soul through the interior life—would be very confused with today's Gospel lesson (in the ordinary form); for, in it, our Blessed Lord is approached by a woman who is drawn to him solely by faith, seeking nothing for herself, but begging him to help her tormented daughter. She's persistent, so much so that, in Matthew's account of this encounter, the disciples ask him to “Rid us of her..., she is following us with her cries” (Matt. 15: 23 Knox). He turns to her and says, “Let the children have their fill first; it is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs.” (Mark 7: 27 Knox); in other words, I'm not going to help you; you're not even a Jew. And I'm sure you're waiting with baited breath for me to explain to you how our Lord isn't really saying what he seems to be saying, and how this is all the result of some inferior translation, which, as you know, is something that I often like to do.

But I'm not going to do that today, because there's nothing wrong with this translation. He appears to be rude to this poor woman because he is. He seems to be telling her that, because she's not of the same nationality as he, he's not interested in her problem because that, in fact, is what he's telling her. There is no mistake. He even goes so far as the get personally abusive, telling her, “It is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs.”

Of course, there is a method in our Lord's madness which has deep implications for our interior life, and we'll get to that in a moment; but, consider first how this poor woman reacts to this very brazen insult: "Yes, Lord, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters' table" (v. 28 RSV). Now, I don't think there's a woman here who, if they went to a man for help, and he responded by calling her a dog, wouldn't just haul off and slap him silly; but, remember, this woman is desperate. Saint Anselm tells us, in one of his homilies (cf. Golden Chain, MT-MK 4521), that it's clear from the text that this woman clearly believed that Jesus was God, something that most of the Jews with our Lord that day probably didn't yet realize. Keep in mind, too, that she's a Syrophenician. The Syrophenicians were a race of people who had been Jews, but had abandoned the faith and fallen into apostasy, so the Jews threw them out of Israel so as not to be corrupted by them. She's sneaked back across the border for the sole purpose of asking our Lord to help her tormented daughter; she doesn't even want anything for herself. And I think it's safe to assume that there's more than one person here today who will testify that desperation has a way of tearing down the walls of pride. She's come there with a mission, and she's not about to let anything derail her from it, even if it means she has to swallow her pride and take an insult without responding to it.

And here is where we are able to deduce the method in our Lord's madness. He's not so much testing her;—as Saint Anselm told us, she already believes he's God, and he knows this, so he doesn't need to test her faith—but, she does need to be instructed as to why she's doing what she's doing. She's gone there because—as we've said three times now—she's desperate. Her daughter is suffering, she knows that Jesus is in a particular place at a particular time, so she's off. She's not even thinking clearly. By treating her the way he does initially, our Lord forces her to put the breaks on and think about what she's doing, not because there's anything wrong with what she's doing, but because he wants her to understand her own actions: “Propter hunc sermonem vade: exiit dæmonium a filia tua (In reward for this word of thine, back home with thee; the devil has left thy daughter.” (v. 29 Knox). She had no idea that she was acting out of faith, but now she does, and so do the disciples who had initially begged him to send her away.

This is the second lesson we've had now on the permissive will of God. The first was back in July on the feast of Saint Camillus de Lellis: here was a man who, in his youth, had been addicted to gambling, but underwent a conversion and developed a great faith and, because of that faith, wanted to devote his life to Christ as a Capuchin Franciscan friar; but every time he tried it, he failed. Three times he entered the Capuchins, and three times he was either thrown out or left of his own accord. He finally lands in the cesspool of 16th century Rome all depressed and dejected when the second plague hits, and he's moved by the spectacle of so many sick people whom even the care-givers of the Church would not care for out of fear of catching the plague themselves. He gathers around himself a group of people who are willing to disregard their own safety in order to care for the sick around them, eventually being ordained to the secular priesthood, and founding the Order of the Ministers to the Sick. He died of disease himself in 1614 at the age of sixty-five, and was canonized by Pope Leo XIII, who named him the Patron Saint of Hospitals and the Sick. The point being: God knew from the beginning what he was going to do with this man, but he didn't let Camillus de Lellis know that. All those years that Camillus tried to become a Capuchin and failed, God knew exactly what he was going to do with him, but there was an element of pride that had to be boiled out of him first. From the beginning he wanted nothing but to serve our Lord, but he wanted to serve our Lord on his own terms. He needed to learn that, when you want to truly serve God, you don't do what you want; you do what you're told. This is the second lesson we've had now on the permissive will of God. The first was back in July on the feast of Saint Camillus de Lellis: here was a man who, in his youth, had been addicted to gambling, but underwent a conversion and developed a great faith and, because of that faith, wanted to devote his life to Christ as a Capuchin Franciscan friar; but every time he tried it, he failed. Three times he entered the Capuchins, and three times he was either thrown out or left of his own accord. He finally lands in the cesspool of 16th century Rome all depressed and dejected when the second plague hits, and he's moved by the spectacle of so many sick people whom even the care-givers of the Church would not care for out of fear of catching the plague themselves. He gathers around himself a group of people who are willing to disregard their own safety in order to care for the sick around them, eventually being ordained to the secular priesthood, and founding the Order of the Ministers to the Sick. He died of disease himself in 1614 at the age of sixty-five, and was canonized by Pope Leo XIII, who named him the Patron Saint of Hospitals and the Sick. The point being: God knew from the beginning what he was going to do with this man, but he didn't let Camillus de Lellis know that. All those years that Camillus tried to become a Capuchin and failed, God knew exactly what he was going to do with him, but there was an element of pride that had to be boiled out of him first. From the beginning he wanted nothing but to serve our Lord, but he wanted to serve our Lord on his own terms. He needed to learn that, when you want to truly serve God, you don't do what you want; you do what you're told.

And it is no less true for us as it was for him, or as it was for the Syrophenician woman whose daughter our Lord released from her demons. There is not a person here who hasn't suffered a tragedy or endured a hardship or borne a cross that hasn't caused us to wonder what on earth God is up to. Like the Syrophenician woman, we are already people of faith, and so we ask, “Why is this happening? What have I done wrong?” The answer is that we've done nothing wrong; but, if God were to reveal to us the reason for our suffering, or show us his plan for us or the souls of others that will be converted and saved by our trials and acts of reparation, then there would be no merit in the sacrifice. As we already observed, when one sets out to serve the Lord, one doesn't do what one wants; one does what one is told. Saint Paul said it better:

How deep is the mine of God’s wisdom, of his knowledge; how inscrutable are his judgements, how undiscoverable his ways! Who has ever understood the Lord’s thoughts, or been his counsellor? (Rom. 11: 33-34 Knox).

|