As Long as You Have Your Health … and a Full Head of Hair.

The Sixth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the secondary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Leviticus 13: 1-2, 44-46.

• Psalm 32: 1-2, 5, 11.

• I Corinthians 10: 31—11: 1.

• Mark 1: 40-45.

Quinquagesima Sunday.*

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Corinthians 13: 1-13.

• [Gradual] Psalm 76: 15-16.

• [Tract] Psalm 99: 1-2.

• Luke 18: 31-43.

FatherVenditti.com

|

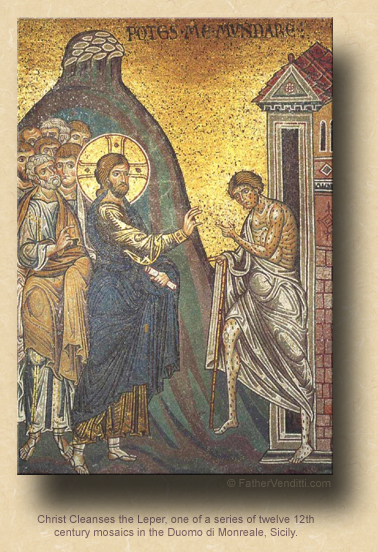

7:05 AM 2/11/2018 — Today's Gospel lesson is an example of what Scripture scholars call the “messianic secret”: Jesus reveals to His disciples who He is, but hides His true identity to the general public. Several times in the Holy Gospel we hear Him speak to the multitudes in cryptic parables, explaining their meaning only in private to his closest disciples, leaving everyone else to think about it. The reason for the messianic secret is unknown;—to know it would be to know the mind of God—and today, we have a rather explicit example of it, with our Lord sternly warning the leper whom he's cured to tell no one about Him. The messianic secret is found principally in Mark's Gospel, but elements of it appear now and then in the others. 7:05 AM 2/11/2018 — Today's Gospel lesson is an example of what Scripture scholars call the “messianic secret”: Jesus reveals to His disciples who He is, but hides His true identity to the general public. Several times in the Holy Gospel we hear Him speak to the multitudes in cryptic parables, explaining their meaning only in private to his closest disciples, leaving everyone else to think about it. The reason for the messianic secret is unknown;—to know it would be to know the mind of God—and today, we have a rather explicit example of it, with our Lord sternly warning the leper whom he's cured to tell no one about Him. The messianic secret is found principally in Mark's Gospel, but elements of it appear now and then in the others.

Some people choose to interpret it in purely pietistic terms, saying that our Lord is simply showing His humility in not wanting to be lauded or praised. I think that's a little simplistic, especially since this command to keep what He's done for someone a secret is not applied universally; He only requires it in certain cases, and I don't think there's a way to figure out why. In this case it may be purely practical, since our Lord is on the move, and every time a crowd gathers around Him He has to stop and deal with them; but, more often than not there's a mystical component to the messianic secret that I don't think we'll ever understand beyond the realm of conjecture.

But the other element in this lesson worthy of our meditation is the command our Lord gives the leper to “go, show yourself to the priest” (Mark 1: 44 NABRE), and there's a reason for this. The Law of Moses is very explicit about the handling of those with skin diseases in a way that seems almost comical to us if the reality of it wasn't so tragic. That's what our first lesson from Leviticus is all about, except that the reading given in our Missal skips a whole bunch of verses, and the missing verses are quite interesting. Here's what the skipped verses tell us:

When whiteness appears on the skin of man or woman, and the priest, examining them, finds it is only a dull whiteness that shews there, he will recognize that it is not leprosy, but ring-worm, and the man or woman is clean. A man may lose the hair on his crown, and still be clean; may lose the hair on his forehead, and still be clean, despite his baldness. But if in the bald patch on crown or forehead a white or reddish tinge is shewing, the priest who finds it there will hold him unclean beyond all doubt; the bald patch is leprous. The man who is infected with leprosy, and segregated at the priest’s bidding, must go with rent garments and bared head, his face veiled, crying out, “Unclean, unclean.” And still, as long as he remains unclean through leprosy, he must dwell away from the camp, alone (Leviticus 13: 38-46 Knox).

Now, that's pretty harsh. Of course, there's little doubt that what's being described here is not the Hansen's disease of modern times, nor can we presume that a Jewish priest in the time of the Pentateuch would have had the medical knowledge to diagnose genuine leprosy if he saw it.

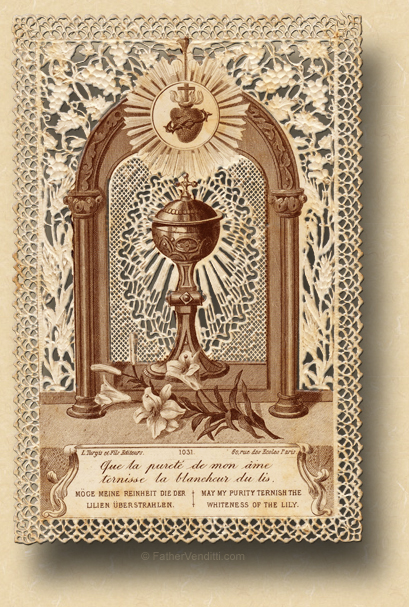

What's important for us to remember is that this Levitical proscription is founded upon the Semitic notion prevalent right through to our Lord's time that chronic illness was the result of sin.  Remember when our Lord encountered the man born blind, His disciples asked him: “Master, was this man guilty of sin, or was it his parents, that he should have been born blind?” (John 9: 3). It makes no sense to us to identify illness or handicap with sin, unless we have embraced the Biblical understanding that sin is a sickness. What's being described in the Book of Leviticus is a precursor of the Sacrament of Penance because, not only is it the job of the priest to declare a person unclean, it's also his job to declare a person clean after a proper examination. This is why our Lord commands the man He's cured to go and show himself to the priest. Once the priest at the temple declares him clean again, the law requires that he offer a sacrifice in thanksgiving to God; until he does so, he cannot reenter the temple, just as we cannot receive our Blessed Lord in Holy Communion until we have been cleansed from sin by the priest: hence, our Lord tells him, “…offer for your cleansing what Moses prescribed…” (v. 44). Remember when our Lord encountered the man born blind, His disciples asked him: “Master, was this man guilty of sin, or was it his parents, that he should have been born blind?” (John 9: 3). It makes no sense to us to identify illness or handicap with sin, unless we have embraced the Biblical understanding that sin is a sickness. What's being described in the Book of Leviticus is a precursor of the Sacrament of Penance because, not only is it the job of the priest to declare a person unclean, it's also his job to declare a person clean after a proper examination. This is why our Lord commands the man He's cured to go and show himself to the priest. Once the priest at the temple declares him clean again, the law requires that he offer a sacrifice in thanksgiving to God; until he does so, he cannot reenter the temple, just as we cannot receive our Blessed Lord in Holy Communion until we have been cleansed from sin by the priest: hence, our Lord tells him, “…offer for your cleansing what Moses prescribed…” (v. 44).

And, just as an aside, here may be a way for us to interpret the messianic secret, at least in this particular case: it's a foreshadowing of the seal of confession.

Lent begins on Wednesday, as you know, and we may or may not having been thinking of what we're going to do for Lent. Chances are, a lot of us haven't thought about it at all; but, before we automatically fall back on the tired, old clichés of giving up deserts or cutting back on TV, we might want to consider something with a little more substance to it, such as a resolution to thank our Lord for the great gift He offers us in the confessional, and make frequent use of it.

Sin is a sickness, a sickness that excludes us from the Temple of our Lord's Sacred Body and Precious Blood; and, it is Christ alone, in the person of the priest, who cures that sickness and declares us clean again.

* Almost all liturgical traditions observe a pre-Lenten season, with the sole exception of the ordinary form of the Roman Rite.

The extraordinary form of the Roman Rite observes a pre-Lenten period lasting for three weeks, known as the Septuagesima Season, consisting of Septuagesima, Sexagesima and Quinquagesima. In English speaking countries, this season is sometimes called “Shrovetide,” because it ends on the day before Ash Wednesday, which is often called “Shove Tuesday.”

The Churches of the Byzantine Rite observe a pre-Lenten season known as the Triodion, lasting for four weeks; it is sometimes preceded by a Sunday “before the Triodion,” as determined by the date of Easter. The first few Sundays of this season are thematic, taken from the Gospel of the day, from which each Sunday gets it’s name. The Sunday before the Triodion is known as the Sunday of Zacchaeus, the First Sunday that of the Publican and Pharisee, and the Second that of the Prodigal Son. The last two Sundays are named after the specific food items which may be eaten during the weekdays prior to them, as the fasting discipline of Lent is gradually imposed: the Sunday of Meatfare and the Sunday of Cheesefare. The day following Cheesefare Sunday is the First Day of the Great Fast, there being no tradition of an "Ash Wednesday."

A pre-Lenten season is also preserved in some of the more traditional branches of the Anglican and Lutheran communions, making the ordinary form of the Roman Rite the only major liturgical Tradition to have completely eliminated it.

|