Confession, Part One: Don't Be Such a Smart Aleck.

The Second Sunday of Advent.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Baruch 5: 1-9.

• Psalm 126: 1-6.

• Philippians 1: 4-6, 8-11.

• Luke 3: 1-6.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Romans 15: 4-13.

• Psalm 49: 2-3, 5.

• Matthew 11: 2-10.

FatherVenditti.com

|

5:06 PM 12/8/2018 —

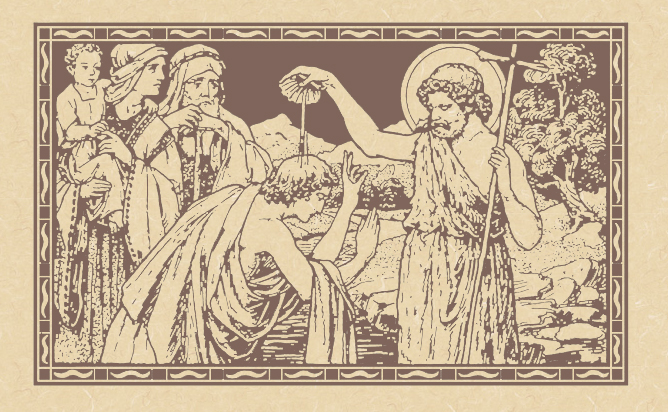

There is a voice of one crying in the wilderness, “Prepare the way of the Lord, straighten out his paths. Every valley is to be bridged, and every mountain and hill leveled, and the windings are to be cut straight, and the rough paths made into smooth roads, and all mankind is to see the saving power of God” (Isaiah 40: 3-5; Luke 3: 4-6 Knox).

The Holy Evangelist Luke quoting the prophesy of Isaiah as he introduces us to John the Baptist. The Holy Evangelist Luke quoting the prophesy of Isaiah as he introduces us to John the Baptist.

John the Baptist is a transitional figure: his life and his death are clearly part of the Holy Gospel and, as such, he's a New Testament saint; but, he is also the last of the prophets who foretold the coming of the Messiah and, as such, is part of the Old Testament legacy. In this sense, he's kind of like Beethoven, who lived in what musical historians call the Classical period, identified by figures like Handel and Hayden and Mozart, but whose music was not of that style, and was an anticipation of the Romantic period that would resonate with the music of Schubert, Tchaikovsky, Saint-Saëns and Rachmaninoff.

Because he comes before Christ, John cannot yet be said to be a Christian, and what the Evangelist calls his “baptism” was not a sacrament, because there were, as yet, no sacraments. The Evangelist calls it a “baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins” (cf. Luke 3: 3), but it clearly has no power in itself to forgive sins since, without yet a Divine Savior to institute it, then suffer and die and rise again to give it sacramental power, it remains merely a symbol. But symbols themselves can be powerful, and John's purely symbolic baptism was. He invented it out of pure common sense: to clean one's body, one uses water; John used water to represent the cleansing of one's soul, the idea being that one would not present oneself to be baptized by John if one was not ready to acknowledge and confess that one had, in fact, sinned. We don't know for a fact whether John required those coming to him to speak their sins out loud, either publicly or privately to him in secret, but I wouldn't be a bit surprised if he did, since he condemns the Scribes and Pharisees because they won't speak their sins.

Which brings us to the topic I've chosen to share with my readers for the Advent Sunday series this year: the Sacrament of Confession or, as it is sometimes called, the Sacrament of Penance or the Sacrament of Reconciliation.*

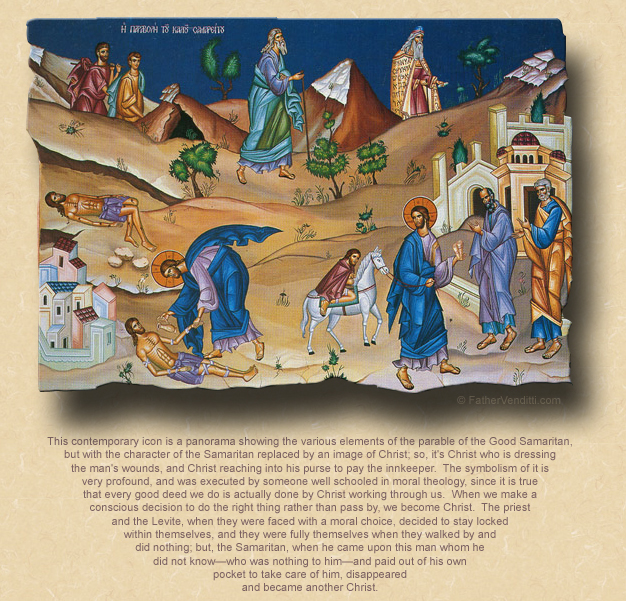

And to begin this journey into the Sacrament of Confession, I would like to call you back to another very familiar Gospel passage, the parable of the Good Samaritan:

It happened once that a lawyer rose up, trying to put him to the test; “Master,” he said, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?” Jesus asked him, “What is it that is written in the law? What is thy reading of it?” And he answered, “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with the love of thy whole heart, and thy whole soul, and thy whole strength, and thy whole mind; and thy neighbour as thyself.” “Thou hast answered right,” he told him; “do this, and thou shalt find life.” But he, to prove himself blameless, asked, “And who is my neighbour?” Jesus gave him his answer; “A man who was on his way down from Jerusalem to Jericho fell in with robbers…” (Luke 10: 25-30 Knox).

And I'm sure you can remember the rest of the parable: our Lord's answer to him is the lovely story about a man who is set upon by bandits and left to die, with the only one willing to stop and help him being a Samaritan—a non-Jew—after more respectable members of Jewish society had passed him by not willing to get involved.

When our Lord explains to the rabbi that we should love our neighbor as ourselves, and the rabbi responds with the question, “But who is my neighbor?” the rabbi, even before he hears the beautiful little story told by our Lord, already knew the answer, and probably so did everybody else who was standing around our Lord that day: our neighbor is everyone, and our Lord makes that point very clearly by making the hero of His story a Samaritan, a member of a race of people hated by the Jews. If you should go back and read the parable from Luke 10—and I recommend you do—notice that after the story is over, when our Lord asks the rabbi which character in the story did the will of God, the guy so hates the Samaritans that he tries to skirt the issue by saying, "Well, it was the one who helped the injured traveler." He can't even bring himself to say the word, "Samaritan," so much has he been conditioned to hate this particular race of people.  He’s hoping, of course, that our Lord will fall prey to the temptation to try and show Himself off in front of an audience of religious scholars by giving them an answer so full of profound and didactic sophistry that the rabbi will be able to pick it apart and find some flaw in it that will enable him to expose Jesus for the charlatan he believes Him to be. But our Lord resists the temptation and sticks to the simplicity of His overall message, responding to the question with a story which makes His meaning perfectly clear. He’s hoping, of course, that our Lord will fall prey to the temptation to try and show Himself off in front of an audience of religious scholars by giving them an answer so full of profound and didactic sophistry that the rabbi will be able to pick it apart and find some flaw in it that will enable him to expose Jesus for the charlatan he believes Him to be. But our Lord resists the temptation and sticks to the simplicity of His overall message, responding to the question with a story which makes His meaning perfectly clear.

There are times when we chafe at simplicity, because simplicity doesn’t give us a way out. We like to take difficult questions, particularly ones that deal with what’s right and what’s wrong, and pick them apart and analyze them and look at them from five or six different angles, because when we do that we have a better chance of finding an answer that’s more to our liking then the one that appears at face value. And we justify this kind of moral sophistry by saying that we want to be thorough, look at every detail, cover all the bases. But covering all the bases doesn’t necessarily guarantee a home run, and sometimes the best play is not to even step up to the plate but accept things as they first appear. Case in point, our Lord’s conversation with the rabbi: he wants to know what he must do to be saved. A very simple question. And our Lord gives him a very simple answer: “What does it say in the Law of Moses?” Answer: Love God above all else, and love your neighbor as yourself. Case closed. Next case.

Now, to understand something about how the rabbi reacts to this, we have to understand something about him. He is, after all, a lawyer. Saint Luke describes him as a “doctor of the law,” which is what a rabbi is. When someone has a question about what the Law of Moses requires in this or that situation, they ask the rabbi because he’s made the study of the Scriptures his life’s pursuit. Now, our Lord is often called Rabbi by His disciples, but He’s never been to school. We have no evidence that our Lord ever received formal training in the Scriptures other than what would have been taught to Him by His parents growing up. And yet, here He is being called Rabbi, being followed by hundreds of people who hang on His every word. If Jesus were a nobody like you and me, the rabbi wouldn’t have any interest in what Jesus is saying; he’d just ignore him. But Jesus is someone who is enormously popular, and people are coming to Him with questions that they would ordinarily go to the Rabbi to ask. It’s possible that he’s a little jealous that Jesus has stolen some of his thunder. So, he asks our Lord what he has built up in his own mind to be a very complex and multifaceted theological question, and our Lord gives him what is essentially a child’s schoolbook answer; not to insult the rabbi but, because, as far as our Lord is concerned, the answer really is that simple. “What must I do to be saved?”

“Well, what’s it say there in Deuteronomy?”

“Well, it says this …”

“Well, go do that, then.”

“But it can’t be that simple???”

“Why can’t it? Because you’ve spent your whole life studying something every child can find out just by reading his Bible? That’s your problem, pal.”

The bottom line is that, whenever we find ourselves faced with a question of right or wrong, and we start analyzing it and going around in circles with it, looking it up on the Internet and consulting experts about it, it’s probably because we just don’t like the simple answer that’s staring us right in the face. Just like the rabbi: he asked our Lord a question, he got his answer; but he didn’t like that answer, so he started to analyze the question further, which is what prompted our Lord to tell the story of the Good Samaritan.

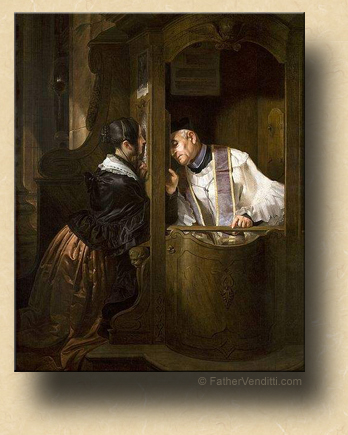

As we continue through the penitential season called Advent, we should begin now to examine our consciences in preparation for confession. And when you go to confession, there is no need to analyze your behavior for the priest, and try to explain why you did what you did, and what all the circumstances were, and how you feel about it. As we will discuss later on in this series of homilies, confession is not counseling, and the priest is not necessarily the most qualified person to help us work through our personal problems. I know that some of you, when you come to confession to me, seem kind of surprised that I don’t ask a lot of questions or try to give some sort of advice. And that’s not out of disinterest or laziness; it’s by design. Experience has taught me over the years that confession is one of those things in which the simpler it is the better. To try and rehash all the things that brought you there in the first place is not really helpful from a spiritual point of view. You go in, you tell the priest what you did and how many times you did it, get your penance, get absolution and get out. That way it’s less traumatic, and maybe you’ll be more inclined to come back to confession more often. After all, what you're there to receive is not advice, it's absolution, and the grace to be more aware of your sins in the future and increased grace to resist temptation. And all of that we will discuss later in the weeks to come.

But for now, let us resolve to examine our consciences in preparation for confession sometime during this season; and, if you find yourself dwelling on things and trying to figure out things, stop. There’s no need. You know that when you walk into the confessional you’re going to walk out forgiven. The only person who would not be forgiven in confession is the person who thinks he’s done nothing wrong, or who is not sorry for what he’s done, and those people don’t go to confession. But if you’re willing to walk into a confessional, then it has to be because you’re sorry for whatever sins you’re aware you’ve committed. Which means you already fulfill the requirements the priest needs to absolve you.

So, let’s resolve to be confident. Let’s resolve to be honest with ourselves and with God. Let’s begin, perhaps a little each evening before we go to bed, to recall the things we did or failed to do since our last confession of which Christ would not approve, so that we can confess our sins cleanly and openly, and prepare to meet the birth of our Lord with a clean slate and an untroubled conscience.

* Back in the years when I served as a pastor, and even after that at the Shrine of our Lady of Fatima, it was often my custom to preach an ongoing series during the Sundays of Advent (or, as it is known in the Ruthenian Church, Philip's Fast). The last one I preached while serving in the Byzantine Tradition was on the Divine Liturgy; after returning to the Latin Church, I resurrected my first Advent series, on the Sacrament of Confession. Inasmuch as I'm no longer preaching on Sundays, I have decided to adapt this series on Confession for the readers of this web site.

|