A Teacher of Moderation, a Model of Faith, and an Example of Virtue.

The First Friday of Advent; or, the Memorial of Saint Nicholas, Bishop.

Lessons from the feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 29: 17-24.

• Psalm 27: 1, 4, 13-14.

• Matthew 9: 27-31.

|

When a Mass for the memorial is taken, lessons from the feria as above, or from the proper:

• Isaiah 6: 1-8.

• Psalm 40: 2, 4, 7-10.

• Luke 10: 1-9.

…or, any lessons from the common of Pastors for a Bishop.

|

The Third Class Feast of Saint Nicholas, Bishop & Confessor; and, the Commemoration of the First Friday of Advent.*

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Hebrews 13: 7-17.

• Psalm 88: 21-23.

• Matthew 25: 14-23.

FatherVenditti.com

|

10:06 AM 12/6/2019 — Today we are observing the Memorial of Our Holy Father Nicholas the Wonder-worker, Archbishop of Myra in Lycia. In fact, during this season of Advent we celebrate the feasts of number of important saints from the early sub-Apostolic period;—the first 350 years of the Church's existence—and, almost without exception, we know a lot more about them than we do about Nicholas of Myra; saints whose service to the Church seems to have been far more outstanding than his: for example, the Apostle Phillip and his brother Andrew; or Saint John of Damascus and Saint Ambrose of Milan, whose theological writings helped to form and guide the early Church and whose memorial is tomorrow. And yet, their feast days are not celebrated with nearly as much solemnity around the world as that of Saint Nicholas;—in the Ruthenian Church in which I used to serve today is a Holy Day—and yet, about him we know practically nothing. Most of the stories we were taught as children connected with his life belong more to legend than to history, and even most of the history we know we can’t prove with any certainty. 10:06 AM 12/6/2019 — Today we are observing the Memorial of Our Holy Father Nicholas the Wonder-worker, Archbishop of Myra in Lycia. In fact, during this season of Advent we celebrate the feasts of number of important saints from the early sub-Apostolic period;—the first 350 years of the Church's existence—and, almost without exception, we know a lot more about them than we do about Nicholas of Myra; saints whose service to the Church seems to have been far more outstanding than his: for example, the Apostle Phillip and his brother Andrew; or Saint John of Damascus and Saint Ambrose of Milan, whose theological writings helped to form and guide the early Church and whose memorial is tomorrow. And yet, their feast days are not celebrated with nearly as much solemnity around the world as that of Saint Nicholas;—in the Ruthenian Church in which I used to serve today is a Holy Day—and yet, about him we know practically nothing. Most of the stories we were taught as children connected with his life belong more to legend than to history, and even most of the history we know we can’t prove with any certainty.

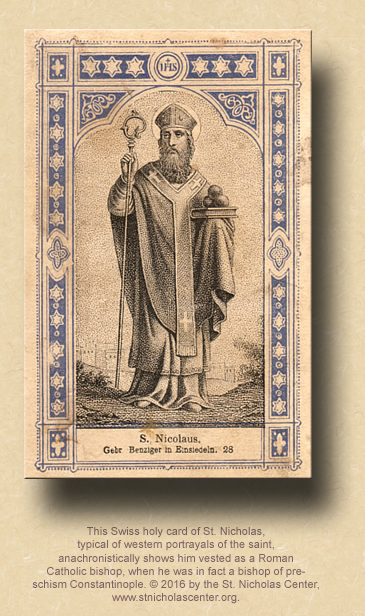

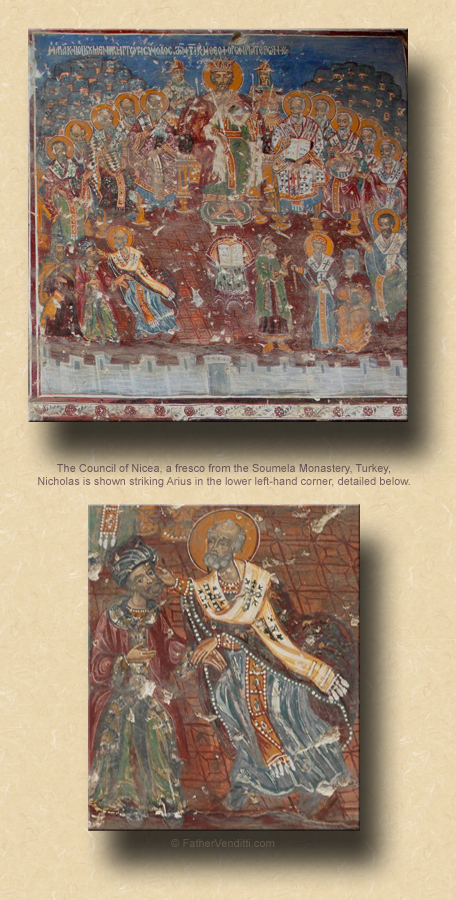

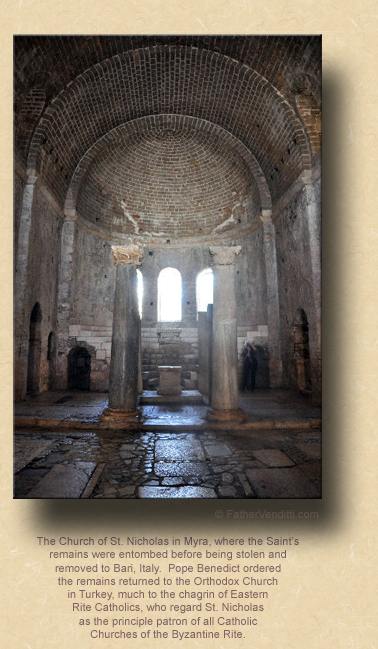

Historians over the centuries have posited that he made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, that he took part in the Council of Nicea where the Creed we recite every Sunday was composed, that he was imprisoned during the reign of the Emperor Diocletian; and, if we can’t be certain about even these innocuous sounding facts, then what are we to think of the hundreds of miracles and acts of charity attributed to him by popular legend—which is why he is called the Wonder-worker? He’s credited with the setting free of captives, with saving schoolboys from death and young girls from dishonor. We all know the stories about how he supposedly distributed gifts to the poor and paid the dowries of girls so that they could marry and so avoid being sold into slavery.  I have somewhere an icon which I used to display in church when I was pastor of a Byzantine parish, which shows him rescuing some sailors caught in a storm at sea, hence his title “Hope of Mariners,” which is just one title out of many. Probably one of the most popular legends about him among Eastern Christians is how, as a bishop in attendance at the Council of Nicaea, as the heretic priest Arius was expounding on his theory that Jesus was not God, Nicholas couldn’t contain himself anymore and rose from his seat to slap Arius across the face, for which he was expelled from the Council. There’s a famous fresco in the Soumela Monastery in Turkey, built toward the end of the fourth century, that depicts the Fathers of the Council of Nicea, showing them all seated serenely around the Emperor Constantine, and in the lower left-hand corner it shows Nicholas grabbing Arius with one hand and landing a right hook on him. As early as the sixth century a church had been dedicated to him in Constantinople. So anxious were people to have relics of him that in 1087 merchants stole his body from Myra where he was bishop and brought it to the Italian city of Bari, where it remained until very recently; and where, we are told, he continued to work miracles. I have somewhere an icon which I used to display in church when I was pastor of a Byzantine parish, which shows him rescuing some sailors caught in a storm at sea, hence his title “Hope of Mariners,” which is just one title out of many. Probably one of the most popular legends about him among Eastern Christians is how, as a bishop in attendance at the Council of Nicaea, as the heretic priest Arius was expounding on his theory that Jesus was not God, Nicholas couldn’t contain himself anymore and rose from his seat to slap Arius across the face, for which he was expelled from the Council. There’s a famous fresco in the Soumela Monastery in Turkey, built toward the end of the fourth century, that depicts the Fathers of the Council of Nicea, showing them all seated serenely around the Emperor Constantine, and in the lower left-hand corner it shows Nicholas grabbing Arius with one hand and landing a right hook on him. As early as the sixth century a church had been dedicated to him in Constantinople. So anxious were people to have relics of him that in 1087 merchants stole his body from Myra where he was bishop and brought it to the Italian city of Bari, where it remained until very recently; and where, we are told, he continued to work miracles.

When Kaiser Otto II took a Greek woman as his empress, he brought not only her but also her devotion to Saint Nicholas to Germany, which has the dubious distinction of having turned this popular saint into something called Santa Claus.

Probably no other saint has been more portrayed both in western art and eastern iconography; and many Eastern Catholic Churches, including the Ruthenian Church I served for almost twenty years, count Saint Nicholas as their patron.  In fact, they have more Churches named for him than any other single saint;—I know because I was pastor of a couple of them over the years—and every icon screen they have shows his image. And yet, in spite of all of this, there are only two facts we know about him for certain: that he was bishop of a town called Myra in Asia Minor, and that he died sometime around the middle of the fourth century. In fact, they have more Churches named for him than any other single saint;—I know because I was pastor of a couple of them over the years—and every icon screen they have shows his image. And yet, in spite of all of this, there are only two facts we know about him for certain: that he was bishop of a town called Myra in Asia Minor, and that he died sometime around the middle of the fourth century.

How these things happen is hard to say. Many of the legends connected with Saint Nicholas probably have some basis in fact; but when a story is passed down over generations by word of mouth, it can’t help but be embellished and fancified. Lord only knows what Saint Nicholas himself would think of some of the stories told of him over the centuries. But if every legend has some basis in fact, then there is some significance to the fact that most of those legends have to do with great acts of charity and help to others, as well as wise and prudent service as a bishop. In the Byzantine Liturgy there is a verse which is sung by the faithful just prior to the readings—sort of corresponding to the Responsorial Psalm in our Liturgy—taken mostly from the writings of the Fathers of the Church, called the Troparion; and, the Troparion for the feast of Saint Nicholas is one which almost everyone in the Eastern Churches knows by heart: “The sincerity of your deeds has revealed you to your people as a teacher of moderation, a model of faith, and an example of virtue.”

See, most of these other saints that we commemorate during Advent—Ambrose of Milan, John of Damascus, Clement of Rome, Gregory the Decapolite—they’re all remembered as great theologians and thinkers, great teachers and, in the case of Saint Clement, a great pope. But Saint Nicholas isn’t remembered for any of that. If he did preach great sermons like Saint Ambrose, they were never written down; if he had been a great teacher and administrator like Saint Clement, no one remembered it; if he ever did write great volumes of theological works like Saint John Damascene, no one knows what they were. What he’s remembered for—what all the legends about him, true or not, point to—is exactly what is sung of him by Eastern Christians: “The sincerity of your deeds…”

So, even if we were to play devil’s advocate and presume that all of the cute little stories about Saint Nicholas are just bologna, any historian worth his salt would still have to agree that, if all those stories seem to paint a picture of the same kind of man, then, even if the stories themselves are not true,  it must be because that was the kind of impression he left with those who remembered him, and who passed that on by word of mouth to others over a fifteen hundred year period. it must be because that was the kind of impression he left with those who remembered him, and who passed that on by word of mouth to others over a fifteen hundred year period.

We’re all familiar with the cliché: “actions speak louder than words.” Well, Saint Nicholas is the historical proof of that. When a man leaves absolutely no written record of himself behind, it’s almost a sure bet that a millennium and a half later he’s going to be forgotten. If he isn’t, it can only mean that the way he lived his life must really have made an impression!

So many of the ancient Fathers of the Church we remember because they left behind great writings that survive and continue to nourish the Church today; if they hadn’t, they’d have been forgotten long ago. If Saint Ambrose’s glorious sermons, which inspired Saint Augustine to convert, had never been written down and preserved, we wouldn’t know his name today. If Saint Clement had not written his famous Letter to the Corinthians about papal authority, who would have remembered him? If Saint John Damascene hadn’t written so beautifully about the Mother of God in anticipation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, why would we have remembered him? And maybe this is the reason that Saint Nicholas’ feast is celebrated so universally while the other saints feasts are not. There are a lot of saints who lived what they believed;—if they didn’t, they wouldn’t be saints—but there are very few, at least from so early a period, who are remembered for the example of their lives alone; and even fewer who’s lives continue to inspire devotion long after the actual events of their lives have been forgotten.

But when you think about it, you don’t need to know the events of such a life; for all you have to do is open up the Gospel and read the life of Christ; and there you will find the life of every saint; for that is really what a saint is: someone who reproduces, in his own life, the life of Christ. Of course, when you read the life of Christ you realize very quickly that this is exactly how Jesus is asking all of us to live. And as we reflect, during this Advent, on our final judgment—which is what this season is really all about—if we have not yet thought much about what we will say in confession, we might want to take that Troparion of Saint Nicholas from the Byzantine Liturgy, and turn it into an examination of conscience: do the sincerity of my deeds reveal me to others as a teacher of moderation, a model of faith and an example of virtue? And, if not, how can I change to make it so?

* In the extraordinary form during Advent, whenever a feast is observed, the feria is commemorated, but a Mass is not permitted for this commemoration; rather, the commemoration is made at Mass by an additional Collect, Secret and Postcommunion added to those of the feast. The commemoration is made at Lauds and Vespers by adding an additional antiphon, verse and Collect to those of the feast.

|