When Bad Things Happen to Good People; or, Will the Real Jesus Please Stand Up?

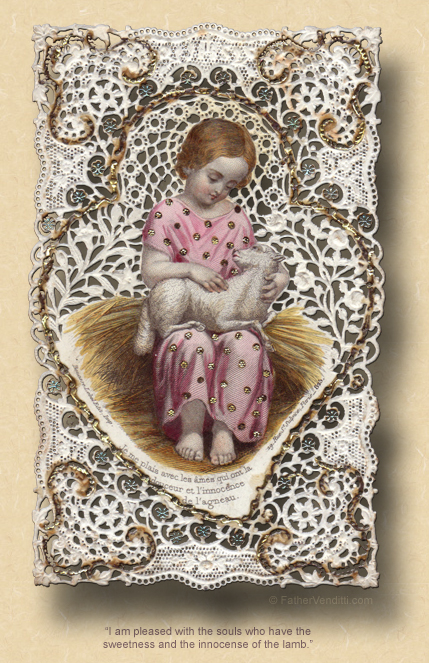

The Feast of the Holy Innocents, Martyrs.

Lessons from the proper, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I John 1: 5—2: 2.

• Psalm 124: 2-5, 7-8.

• Matthew 2: 13-18.

The Second Class Feast of the Holy Innocents, Martyrs; and, the Commemoration of the Fourth Day of Christmas.*

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Apocalypse 14: 1-5.

• Psalm 123: 7-8.

• Matthew 2: 13-18.

FatherVenditti.com

|

7:38 AM 12/28/2017 — There is no easy explanation for suffering, least of all for the suffering of the innocent. Saint Matthew’s narrative, which we read today, shows us the suffering of some children who gave their lives for a Man and a Truth they didn’t even know, and today is their feast day. The Holy Innocents were infants, and could hardly have understood what was happening to them. We can read about them and feel sorry for them on an intellectual level, but it hardly has the same impact as when we suffer, then end up asking that quintessential question we all ask at some point in our lives: I’ve lived a good life; why is God letting this happen to me? 7:38 AM 12/28/2017 — There is no easy explanation for suffering, least of all for the suffering of the innocent. Saint Matthew’s narrative, which we read today, shows us the suffering of some children who gave their lives for a Man and a Truth they didn’t even know, and today is their feast day. The Holy Innocents were infants, and could hardly have understood what was happening to them. We can read about them and feel sorry for them on an intellectual level, but it hardly has the same impact as when we suffer, then end up asking that quintessential question we all ask at some point in our lives: I’ve lived a good life; why is God letting this happen to me?

You might recall, some time ago, we spent considerable time on this question. You might remember the Prophet Habakkuk complaining to the Lord about the apparent triumph of evil over good, lamenting the mistreatment of the chosen people by invaders who flaunt their scandalous behavior:

How long, O Lord? I cry for help but you do not listen! I cry out to you, “Violence!” but you do not intervene. Why do you let me see ruin; why must I look at misery? (Hab. 1: 2-3 RM3).

And there in the Prophet’s words you have every third confession I’ve ever heard as a priest. And God answers the Prophet with a call to patience and hope, and a reminder that the day will come when evil will be punished and the righteous will triumph; it’s just not our right to know when or how.

You might remember the time we spent picking apart the Apostle Paul’s counsels to his friend, Timothy. He made Timothy Bishop of Ephesus, but the Ephesians rejected him because they thought he was too young and inexperienced for the job; and, Timothy himself wonders if they might be right, as he is worn down by their constant criticisms, their disobedience and lack of cooperation. Paul exhorts him to remember that he’s been consecrated a bishop by the laying on of hands, and that the grace of that sacrament will see him through, but only if he keeps faith.

And our Lord Himself tell us, “If you had faith the size of a mustard seed, you would say to this mulberry tree, ‘Be uprooted and planted in the sea,’ and it would obey you” (Luke 17: 6 RM3). No disrespect intended to our Lord, but I’ve tried it; it doesn’t work … unless, of course, I don’t have faith the size of a mustard seed, which is altogether possible, I suppose.

Of course, the really extensive treatment of this whole matter of the suffering of the innocent is in the Book of Job, the whole of which is centered on this very question: why do bad things happen to good people? Job never gets an answer to his question, nor does he give one. He goes as far as he can to explain to his friends why he continues of have faith in God in spite of all the horrible things that have happened to him; and, as we read though it and hear Job’s sometimes moving, sometimes comic, answers to his friends arguments, our excitement builds as we anticipate a grand resolution which will finally, once and for all, answer this universal question; but, when we finally get to the epilogue, we’re disappointed to learn that the answer never comes.  Part of the reason for this we also touched on last year, when we were looking at what is called the “Wisdom Literature” of the Bible, of which Job is a part: the Jewish people had no concept of an afterlife until the advent of the Pharisees some sixty years or so before the time of our Lord, so the idea that we suffer in this world in order to be rewarded in the next is an insight that escapes Job. The conclusion to the book of Job, in which Job has everything he’s lost restored to him, is a deus ex machina which gives the impression that all we have to do is persevere in faith and everything will end up OK. At no time does the book even attempt to actually answer the question posed at the beginning: why do bad things happen to good people. Part of the reason for this we also touched on last year, when we were looking at what is called the “Wisdom Literature” of the Bible, of which Job is a part: the Jewish people had no concept of an afterlife until the advent of the Pharisees some sixty years or so before the time of our Lord, so the idea that we suffer in this world in order to be rewarded in the next is an insight that escapes Job. The conclusion to the book of Job, in which Job has everything he’s lost restored to him, is a deus ex machina which gives the impression that all we have to do is persevere in faith and everything will end up OK. At no time does the book even attempt to actually answer the question posed at the beginning: why do bad things happen to good people.

But forget last year; go back a couple of years, if you can, when I preached a series comparing Job to the Prophet Jonah. Both men are presented to us as polar opposites: Jonah is a bitter and angry man, and Job is a pious innocent; both men suffer great loss and have bad things happen to them, but they react in totally different ways. Jonah, in his bitterness, won’t talk to God and cuts off all contact with Him, even when God tries to reach out to him in the end, and the book ends with Jonah estranged from God; Job never stops praying, and ends up having everything restored to him. In fact, Job’s statement of faith in the first chapter is almost impossible to comprehend given the fact he doesn’t believe in an afterlife: “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return; the Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord” (Job 1: 21 RSV). That is simply not a faith to which any of us can relate without some concept of a resurrection from the dead, which Job didn’t have.

I hate to sound like a broken record, but how many times must it be said? Of all the themes upon which our Blessed Lord touches in the Holy Gospels, this is the one of which He speaks most frequently, which is always constant and never changes: that reward and punishment do not happen in this life, but in the next! If you can’t live with that, then you need to go and find yourself another religion, because Christianity is not for you.

We keep wanting to view our Blessed Lord like some schmaltzy painting on black felt which we have hung next to our Elvis on black felt. I’ve actually seen that, by the way, in someone’s living room: an effeminate-looking Jesus on black felt next to an Elvis on black felt. The Jesus on black felt looks effeminate because that’s how some people have completely reinvented our Lord: a mild, meek milquetoast who requires nothing, and whose sole purpose is to kiss our boo-boos and make them feel better. The real Jesus is the One we read about in the Gospels, the one Who says,

Does [the master] thank the servant because he did what was commanded? So you also, when you have done all that is commanded you, say, “We are unworthy servants; we have only done what was our duty” (Luke 17: 9 RSV).

And what is our duty? To obey the Commandments, to live the Gospel, to admit to our sins when we fall and seek out our Lord’s absolution in confession, and to steal ourselves against further sin and temptation through the grace of the sacraments until that day that we are called home to the Lord to enjoy the reward that awaits us in heaven. Or, as the Baltimore Catechism so correctly put it:

Why did God make me? God made me to know Him, to love Him, and to serve Him in this world, and to be happy with Him for ever in the next (Balt. Cat. 1, q. 6).

* In the extraordinary form on feasts during privileged seasons, the ferial day is commemorated by the Collect, Secret and Postcommunion of the feria being added to those of the feast.

|