The Paradox of Christmas.For Vespers & the Divine Liturgy of St. Basil the Great on the Paramony of the Nativity: Genesis 1:10-13;

Numbers 24:2-3,5-9,17-18;

Micah 4:6-7,5:2-4;

Isaiah 11:1-10;

Jeremiah 3:35-4:4;

Daniel 2:31-46,44-45;

Isaiah 9:6-7;

Isaiah 7:10-16,8:1-4,9-10;

Hebrews 1:1-12;

Luke 2:1-20. For the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom on Christmas Day: Galatians 4:4-7;

Matthew 2:1-12. The Feast of the Nativity of Our Lord, God & Savior, Jesus Christ.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

1:12 PM 12/25/2013 — “She brought forth a son, her first-born, whom she wrapped in his swaddling-clothes, and laid in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn” (Luke 2:7).

Here's a thought that I shared with you many years ago, so most of you probably won't remember it. The services of our Byzantine Tradition surrounding the birth of our Lord all took their form during a time when people had little else to do; the ground was frozen so there was no planting or harvesting to be done. I know a few of my parishioners who still observe the tradition of the Holy Supper; but, that's a very ethnic tradition, and most of my parishioners have never heard of it.  The different services offered in church for the Nativity of Our Lord were never intended to be items on a liturgical salad bar; you didn't choose one, you went to all of them. Then, after our Church came into union with Rome, our services began to change as we sought to become as Catholic as possible, with the Vespers and Liturgy of St. Basil sometimes pushed back to Christmas Eve morning, with Great Compline being celebrated very late at night in imitation of the Latin Church's Midnight Mass. When the schema of our services was restored a few years ago, everything was put back into its original order, but times had changed: people no longer have the time to attend all the services, and priests who are pressed into serving more than one parish can't provide them; and, the service that most often gets dropped is the one with which most people were familiar in the old days: the Great Compline. What's more, the Scripture readings about the birth of Our Lord are spread out among the different services; so, when someone attends only one service, he won't hear most of them. In the case of the most detailed and endearing account of our Lord's birth—the one from Luke—it's only heard by those attending the Vesperal Liturgy of St. Basil on Christmas Eve, which is why I repeated the last verse of it for you. The different services offered in church for the Nativity of Our Lord were never intended to be items on a liturgical salad bar; you didn't choose one, you went to all of them. Then, after our Church came into union with Rome, our services began to change as we sought to become as Catholic as possible, with the Vespers and Liturgy of St. Basil sometimes pushed back to Christmas Eve morning, with Great Compline being celebrated very late at night in imitation of the Latin Church's Midnight Mass. When the schema of our services was restored a few years ago, everything was put back into its original order, but times had changed: people no longer have the time to attend all the services, and priests who are pressed into serving more than one parish can't provide them; and, the service that most often gets dropped is the one with which most people were familiar in the old days: the Great Compline. What's more, the Scripture readings about the birth of Our Lord are spread out among the different services; so, when someone attends only one service, he won't hear most of them. In the case of the most detailed and endearing account of our Lord's birth—the one from Luke—it's only heard by those attending the Vesperal Liturgy of St. Basil on Christmas Eve, which is why I repeated the last verse of it for you.

So much for today's excursion into useless trivia. Having repeated the verse to you, I ask the question:—and this is the repeat part, because it was the focus of a Christmas homily I preached some years ago—What think you of the innkeeper in Bethlehem? I've often felt sorry for him. Little did he know that he was turning away God. Of course, we like to think that had he known, he would have rushed to throw somebody else out of the hotel, to give the room to Mary and Joseph—or even, perhaps, give them his own room—something of which our Lord would not have approved, anyway.

The journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem in Judea was about three or four days, over rough terrain; and, with Mary being nine months pregnant, you can bet it was an uncomfortable trip. Perhaps, because of the bumpy ride, Mary was already in labor;—at the very least she must have been in tremendous discomfort—and, Joseph, being anxious to find some kind of shelter, decided to scope out the caves on the outskirts of town which some of Bethlehem's citizens had turned into stables for their livestock. At least there, he thought, there would be some straw to keep the baby and his mother warm for the night, and a roof to keep out the rain.

What are we to think of the innkeeper? Is he guilty of turning away God that first Christmas night? Most of us would probably say, "No. How could he be? How was he supposed to know that this scruffy-looking man and his pregnant wife, both of them covered with the dirt of the road, were the parents of the Messiah?" Wouldn't it be ironic if, thirty years later, that innkeeper was part of the crowd listening to our Lord tell the parable where the condemned say, "Lord, when was it that we saw thee hungry, or thirsty, or a stranger, or naked, or sick, or in prison, and did not minister to thee? And he will answer them, Believe me, when you refused it to one of the least of my brethren here, you refused it to me" (Matt. 25:44,45).

It's an interesting question: to what extent do we excuse the conduct of the innkeeper—who was, after all, a business man—because Mary and her husband, didn't look much like the door through which God was coming into the world? Simeon had no problem recognizing the Messiah. When Joseph and Mary took Jesus to the temple in Jerusalem to be circumcised, old Simeon, whom everyone regarded as a pious kook, snatched the baby out of Mary's arms, lifted him up toward heaven, and thanked God that he had been permitted to see the Messiah before he died. How did he know that? Did the child Jesus have the word "Messiah" tattooed on his forehead?

Thirty years later, when Jesus was walking along the shores of the Sea of Galilee, and he stumbled across Simon and Andrew who were fishermen, and he said to Simon, "...henceforth thou shalt be a fisher of men" (Luke 5:10). The Gospel says that they immediately dropped their nets and followed him; and they followed him for three years until his death and resurrection, and then they both died for him. Why? If you were sitting at work, doing your job, and some stranger came up to you and said, "Forget all that, just come with me," are you going do it? Probably not; and, chances are, you would at least ask, "Who the heck are you?" But the Gospel doesn't say that Simon asked any such question, nor does it indicate that he had ever met or seen Jesus before; it simply says, "So, when they had brought their boats to land, they left all and followed him" (5:11).

So, in our evaluation of the innkeeper, do we still wish to maintain that it wasn't his fault because nobody told him that it was God knocking at his door? Nobody told Simeon. Nobody told Simon and Andrew, and they accepted Jesus. You see, the whole life of our Blessed Lord on Earth is a series of meetings with people, some of whom reject him and some of whom accept him. The first person God meets during his stay on Earth is John the Baptist. When God was still in her whom, Mary went to visit her cousin, Elizabeth, who herself was pregnant with the future John the Baptist. And the Gospel says that as soon as Elizabeth heard Mary's greeting, the baby in her womb leaped for joy: even as a fetus, John accepted Jesus as God, and rejoiced. The second person Jesus meets is the innkeeper, who rejects him. And so it goes throughout our Lord's life on earth. Many people encounter Jesus: some will accept him, some will reject him.

What about us? What think we of Christ? Do we accept him or reject him? Now, I could walk up to each one of you in this church right now, and ask you that question, and without hesitation you would tell me that you accept the Son of God. But, then again, so would the innkeeper, had he recognized Christ. The point is, he didn't. Assuming he was a Jew, he was looking forward to the coming of the Messiah like everyone else; only he didn't expect him to be born of a woman traveling with her husband from Nazareth. And when you read the Gospel through, you'll find that all the people who end up rejecting Jesus do so because he wasn't what they expected.

It is very easy, my friends, to come to church at Christmas time and accept Christ as a baby lying in a crib.  It's an image of God that doesn't repel us because it doesn't challenge us—so much easier to swallow than the image of the broken and bloody body of Christ hanging on the Cross, for example. There are no consequences to kneeling at the foot of the manger; there are dramatic consequences to kneeling at the foot of the Cross, because one who kneels at the foot of the Cross knows what the Gospel is all about. It is not about lights and trees and gifts and a throwback to memories of our childhood. It is about sacrifice and conversion and turning away from sin. It is about fidelity, especially when fidelity isn't easy: fidelity in one's marriage, fidelity in one's duties to Christ's Church, fidelity to the teaching of Christ as it comes to us through his Church. It's an image of God that doesn't repel us because it doesn't challenge us—so much easier to swallow than the image of the broken and bloody body of Christ hanging on the Cross, for example. There are no consequences to kneeling at the foot of the manger; there are dramatic consequences to kneeling at the foot of the Cross, because one who kneels at the foot of the Cross knows what the Gospel is all about. It is not about lights and trees and gifts and a throwback to memories of our childhood. It is about sacrifice and conversion and turning away from sin. It is about fidelity, especially when fidelity isn't easy: fidelity in one's marriage, fidelity in one's duties to Christ's Church, fidelity to the teaching of Christ as it comes to us through his Church.

You see, the whole world is filled with people who would much rather kneel at the foot of the manger than at the foot of the Cross; that's why so many people come to church at Christmas time who never come any other time, and that's why they can't understand things like the moral teaching of the Church, or the obligations that are required of members of Christ’s Church. And they're equally as confused when you try to tell them about the martyrs, and explain why so many people, down through the centuries, were willing to give their lives for Christ. They can't understand these things, because the only image they have of God is of a baby lying in a manger. After that, they don't walk with Christ anymore. Those who walk with Christ all the way know that the manger is only the beginning, that the rejection of Christ by the innkeeper is just the first of many. They are the ones who walk with him to the end, even up the mountain of Calvary, to stand at the foot of the Cross. They are the true friends of Christ. Their image of Christ is different, and that's why they are able to understand what so many cannot.

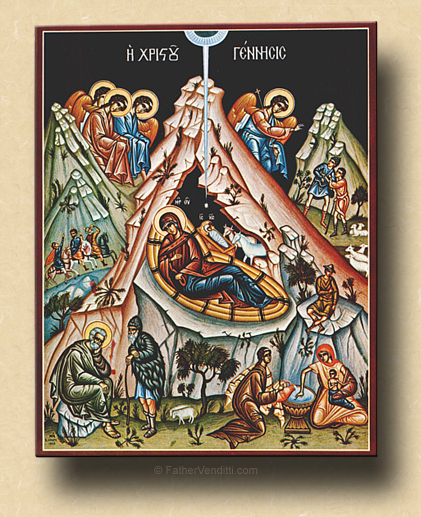

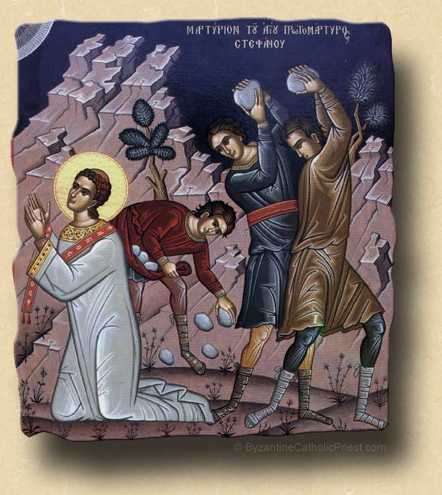

Before leaving Church today I would ask you to take a close look at the icon of the Nativity I've placed on the tetrapod. You should know by now that everything in an icon is significant;—nothing is just a decoration—but today I call your attention to only one thing: toward the bottom of the scene, in the center, there grows a small tree; it's not in every Nativity icon, and it looks like an artistic afterthought, but it isn't. It is the tree from which the wood of the cross would be taken. In our Byzantine Tradition, the day after Nativity is celebrated as the Synaxis of the Theotokos; but the day after that is the feast of the Archdeacon Stephen, the first martyr; we won't celebrate his feast this year to give my body a day to recover before the weekend; but I want to mention it anyway. His death is described in the Acts of the Apostles. It's so much like our Lord's own death: he prays for the forgiveness of those who are stoning him. Do you think that's all just a tremendous coincidence, or do you think that maybe there's a message in his feast being so close to the birthday of our Lord? Perhaps it's to remind us that this child who lies in the manger has not come to earth simply for us to adore, but he is here for us to follow as well; and, if we choose to follow him all the way, then we're going to end up marching up Calvary.

That, my friends, is the paradox of Christmas. Today we rejoice with the Church at the foot of the manger. Let's us pray that none of us will be missing at the foot of the Cross.

|