I Never Said There Would Be No Math Questions.

The Third Day of the Greater Antiphons.*

Lessons from the feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Judges 13: 2-7, 24-25.

• Psalm 71: 3-6, 16-17.

• Luke 1: 5-25.

The Third Day of the Greater Antiphons; and, Ember Wednesday of Advent.**

Lessons from the feria, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 2: 2-5.

• Psalm 23: 7, 3-4.

• Isaiah 7: 10-15.

• Psalm 144: 18, 21.

• Luke 1: 26-38.

FatherVenditti.com

|

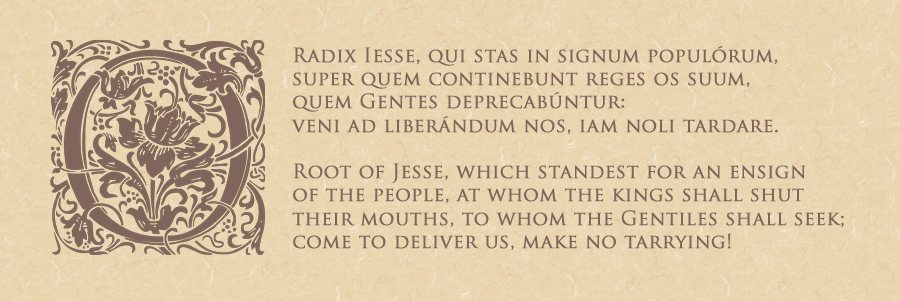

7:18 AM 12/19/2018 — The story of Zechariah learning of the impending pregnancy of his heretofore barren wife is one of those familiar pre-Christmas yarns that we think we all know: the arrival of the Baptist is announced to him by an angel and, because he expresses incredulity at the idea, he's punished with the loss of his voice; but, these are so much more than just straight-forward facts. There is a mystical component to Luke's Gospel that is overlooked, I think, by even the most erudite Scripture scholars, reflecting Luke's own background. We tend to look toward John's narrative as the mystical Gospel, because it deals not so much with fact as with theology and spirituality, and it shines forth even in the most pedestrian of translations. But Luke's Gospel is so sublime in it's mystical elements, most of the people who have translated it probably didn't even understand themselves what they were reading. For sure, it's probably the most beautifully written piece of prose in the Bible, laid out in the most perfectly metered Greek ever put to paper, all of which is completely lost when translated.

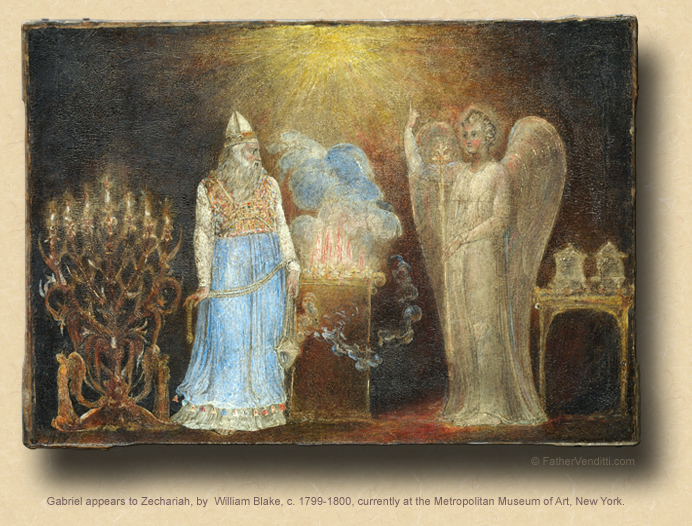

You've heard the cliché, “Poetry is what is lost in translation.” Well, it was never more true than in the Gospel of Saint Luke; after all, he was a Greek, born to Greek parents in Antioch in Syria, baptized a Christian while still a very young man, probably around AD 40. By the year 44 he had become acquainted with the Apostle Paul and, because he himself was not a Jew, he appreciated Paul's efforts to champion the rights of Gentile Christians to the Church in Jerusalem. His pagan origin and frequent travels outside the Jewish world of Palestine brushed away the racial prejudices that sometimes show through in the Hebrew writings of Matthew.

He did not know our Lord personally, and therefore was not an apostle; the events he writes about he learned from Peter and Paul, both of whom he knew well, and wrote his Gospel at Peter's direction. Of all the evangelists he was the most educated, not only trained thoroughly in the Greek classics, but also in medicine, and it comes out in his narrative in unique ways: he's keen and observant, always attuned to any kind of human suffering, always ready to forgive but very intolerant of quacks and hypocrites; and, of all the Gospels, his frequently gives us the psychological context of the events he's describing to us, often telling us how people reacted to things Jesus said and did rather than just relating the events, even sometimes speculating about their inward dispositions.  How many times have we read Luke telling us something like, “Whereupon the Pharisees and scribes fell to reasoning thus, 'Who can this be, that he talks so blasphemously?'” (Luke 5: 21 Knox). Now, how could Luke possibly know what reasoning was going on in the mind of a Pharisee? Because he's a psychiatrist. He knows what makes people tick. How many times have we read Luke telling us something like, “Whereupon the Pharisees and scribes fell to reasoning thus, 'Who can this be, that he talks so blasphemously?'” (Luke 5: 21 Knox). Now, how could Luke possibly know what reasoning was going on in the mind of a Pharisee? Because he's a psychiatrist. He knows what makes people tick.

But Luke is also a convert, which means he knows the faith better than anyone; and, even though he was not raised with the Hebrew Scriptures, he's taken the trouble to learn them from Saint Paul inside and out, and this is exactly what we miss when we read him in a translation; because, this Gospel account of Zechariah receiving the news of his son's birth from an angel is right out of the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible by a legendary group of seventy rabbis begun in the third century BC, the word “Septuagint” from the Latin septuaginta, meaning “seventy.” What Luke has done is to masterfully breath across the first chapter of his Gospel the style, the vocabulary, even the meter of the Septuagint's Greek version of the Old Testament, where we read about women like Sara, Rebecca, Rachel, Anna, all of whom were sterile, and all of whom gave birth, through divine intervention, to one or another of Israel's great leaders. One of those accounts makes up our first lesson today, from the Book of Judges, in which the wife of Manoah, who is barren, receives a message from an angel that she is to bear a son who will deliver Israel from the Philistines, and thus is born Sampson.

That angel is not named, but the angel who appears to Zechariah while he's in the Temple burning incense identifies himself as Gabriel, whose next stop will be to visit our Blessed Mother, but who last appeared in the Bible in the Book of Daniel, where he told Daniel, in answer to his prayers, that, after a period of what he called “seventy weeks of years,” God's people would return to the Holy City of Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple (cf. Daniel 9); and, if you count them, from the moment that Gabriel appears to Zechariah in that same Temple, to the moment our Blessed Lord is brought there to be presented to God in obedience to the Law of Moses, there passes exactly 490 days, or seventy weeks.

At the beginning of Advent I had reminded you of the seamless transition from the Old Testament to the New in response to our Lord referring to John the Baptist as Elijah in Matthew 11 (vs. 2-10). Saint Luke illustrates it in many different ways, not least of which being his more than clever use of the number seventy.  It may be the most brilliant literary device ever conceived, made more so by the fact that it was all inspired by God to tell us the story of our Savior. It may be the most brilliant literary device ever conceived, made more so by the fact that it was all inspired by God to tell us the story of our Savior.

When Gabriel appears to Zechariah, the first words out of his mouth are, “Do not be afraid,” but even this is more than what it seems. The Greek is μὴ φοβοῦ; it appears in the Septuagint version of the Old Testament at least five times—in Genesis, in Joshua, in Daniel—any time someone receives a vision or a message from God. Like the prophet Jeremiah before him, the child Gabriel announces is anointed by God before his birth for the work of redemption. When Gabriel tells Zechariah that his son “is to drink neither wine nor strong drink” (1: 15 Knox), Luke is lifting word for word the Nazarite vow from the Book of Numbers (6: 1-8). When the Angel says that John will “bring back many of the sons of Israel to the Lord their God” (v. 16 Knox), Luke uses the word ἐπιστρέψει, to “turn back,” the same word used when Elijah “turned back” to Mount Sinai to rediscover the God who had once revealed Himself there to Moses (Isaiah 19: 3-13); and, the prophet Malachi uses the same word to declare that Elijah would return before the day of the Lord, to turn Israel back to the law of Moses, and reconcile father to son and son to father (cf. Mal. 3: 22). But the Elijah of which Malachi spoke was John; Gabriel even tells Zechariah explicitly that his son will be another Elijah, just as our Lord did.

But as brilliant and as subtle and as beautiful as Luke's care in crafting of the story of our Lord's entrance into this world is, it pales in comparison to the care taken by God Himself in crafting the means of our redemption. When the blessed Evangelist wrote of these things, he poured so much of his brilliant mind and heart into his words because he understood that he was writing of the greatest event in human history. As we approach our own celebration of these mysteries, let us resolve to apply that same level of care and detail to preparing our souls for it.

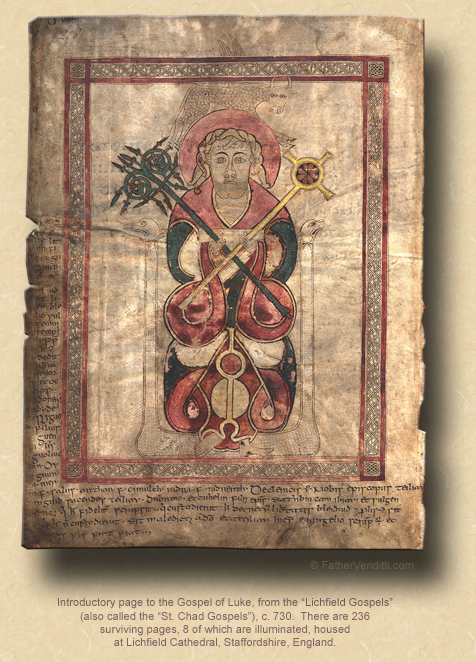

* The Greater Antiphons sung at Vespers, known as the "O Antiphons," and also serving as the verse before the Gospel in the ordinary form, are ordered and utilized differently between the two forms of the Roman Rite. The banners at the top of the pages for the Days of the Greater Antiphons have been created to reflect the original ordering of the antiphons as used in the extraordinary form. For reference, the usages of the two forms compare thus:

| Date: |

Extraordinary Form: |

Ordinary Form: |

| Dec. 17. |

O Sapientia. |

O Sapientia. |

| Dec. 18. |

O Adonai. |

O Adonai. |

| Dec. 19. |

O Radix Iesse. |

O Radix Iesse. |

| Dec. 20. |

O Clavis David. |

O Clavis David. |

| Dec. 21. |

O Oriens. |

O Emmanuel. |

| Dec. 22. |

O Rex Gentium. |

O Rex Gentium. |

| Dec. 23. |

O Emmanuel. |

O Rex Gentium. |

| Dec. 24. |

[The Vigil of Christmas.] |

O Oriens. |

Regarding December 24th: in the Roman Rite, the concept of a vigil differs completely between the ordinary and extraordinary forms. In the ordinary form, a vigil is simply a celebration of the feast the evening before, either prior to or following First Vespers (in the United States, after 4:00 PM). On Solemnities on which an obligation has been attached, this may be fulfilled at either the Mass of the vigil the evening before, or on the feast itself.

In the extraordinary form, the word “vigil” designates the entire day before a First Class Feast, and the Mass for the vigil takes place in the morning. If a feast carries an obligation, this must be satisfied on the feast itself; the extraordinary form does not offer the opportunity to satisfy an obligation on the evening before.

In the extraordinary form, December 24th is the Vigil Day of Christmas and has its own proper texts, the Days of the Greater Antiphons having concluded on the 23rd. In the ordinary form, the morning of December 24th is a day of the Greater Antiphons up to Vespers, at which point it becomes the vigil for Christmas.

** In the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, at the beginning of the four seasons of the year, the fast days known as "Ember Days" thank God for blessings obtained during the past year and implore further graces for the new season; and, their importance in the Church was formerly very great. They are fixed on the Wednesday, Friday and Saturday of specific weeks in their respective seasons: after the First Sunday of Lent for Spring, after Whitsunday (Pentecost) for Summer, after the Feast of the Elevation of the Cross (Sept. 14th) for Autumn, and after the Third Sunday of Advent for Winter. At one time, the Ember Days were obligatory days of fasting; this requirement was dropped in the Missal of St. John XXIII in 1962, but violet vestments are sill worn on Ember Days even when they occur outside the seasons of Advent and Lent, with the exception of the Ember Days that occur during the Octave of Pentecost.

The significance of the Ember Days as days of voluntary fasting is multiple: not only are they intended to consecrate to God both the liturgical seasons and the various seasons in nature, they also serve as a penitential preparation for those preparing for the Holy Priesthood. Ordinations in the extraordinary form generally take place on the Ember Days, and the Faithful are encouraged to pray on these days for good Priests.

Ember Days are ferias of the second class, and have proper Scripture lessons assigned to them.

|