A Long Time Ago, in a Galaxy Far, Far Away…

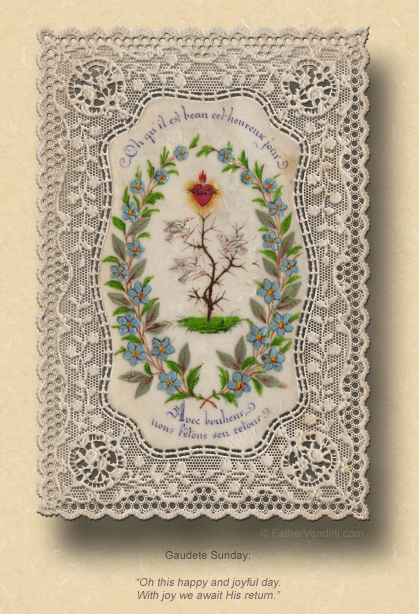

The First Day of the Greater Antiphons; and, the Third Sunday of Advent, known as Gaudete Sunday.*

Lessons from the secondary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 61: 1-2, 10-11.

• [Responsorial] Luke 1: 46-50, 53-54.

• I Thessalonians 5: 16-24.

• John 1: 6-8, 19-28.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Philippians 4: 4-7.

• Psalm 79: 2-3, 6.

• John 1: 19-28.

• [Hymn] Anima Christi…**

FatherVenditti.com

|

7:50 AM 12/17/2017 — Gaudéte in Dómino semper: íterum dico, gaudéte. Dóminus enim prope est. “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I say, rejoice. Indeed, the Lord is near” (RM3). Of course, it's the Entrance Antiphon from which the Third Sunday of Advent takes its traditional name of “Gaudete Sunday,” and it's from Saint Paul. The Introit for the traditional Latin Mass is the same, but actually continues one verse further, and may be more meaningful for some of us: 7:50 AM 12/17/2017 — Gaudéte in Dómino semper: íterum dico, gaudéte. Dóminus enim prope est. “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I say, rejoice. Indeed, the Lord is near” (RM3). Of course, it's the Entrance Antiphon from which the Third Sunday of Advent takes its traditional name of “Gaudete Sunday,” and it's from Saint Paul. The Introit for the traditional Latin Mass is the same, but actually continues one verse further, and may be more meaningful for some of us:

Rejoice in the Lord always: again I say, rejoice. Let your moderation be known to all men: for the Lord is near. Have no anxiety, but in everything, by prayer let your petitions be made known to God (Phil. 4: 4-6 RM 1962)

…from Saint Paul’s letter to the Philippians. And all the lessons presented to us on this day carry with them this sense of joyful expectation. Of course, in both Philippians and the preaching of the Baptist, this joy and expectation is directly linked, as you can plainly see, to the idea that the coming of Christ will mean only one thing: repentance and the forgiveness of sins.

But in addition to being Gaudete Sunday, it is also December 17th, the first day of what I had described for you at the beginning of this season as “Second Advent,” or more traditionally, “the First Day of the Greater Antiphons,” because of the antiphons that are sung at Vespers beginning today. It’s on this day that the focus of the Church's liturgy changes from one of preparation for our final judgment and our Lord's second coming to one of anticipation and preparation for celebrating His first coming as the Holy Babe of Bethlehem. If this day had not fallen on a Sunday, the Gospel lesson would have been the entire first chapter of Matthew’s Gospel, in which he chronicles the genealogy of our Blessed Lord, and for a very important reason.

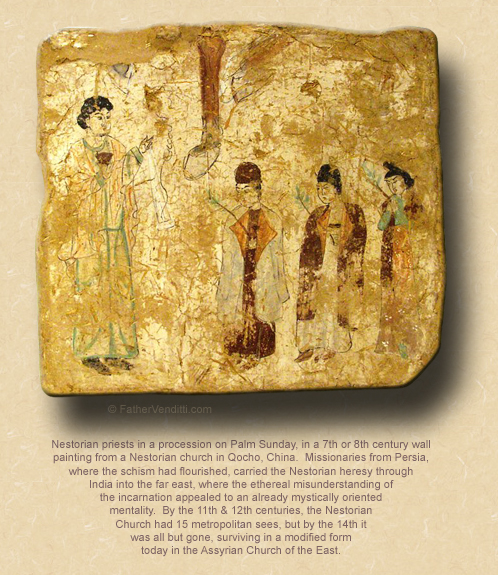

As early as the fourth century, in their attempt to try and understand the mystery of the Incarnation, some Christians began to doubt the reality of it. Nestorius, the Patriarch of Constantinople from 428 to 431, came to believe in a complete separation between the human and the divine in Jesus, and his heresy caused a serious schism in the Church which lasted, in one form or another, until the 14th century. Now, I know that when I talk about these early heresies everyone's eyes gloss over and everyone thinks to themselves, “What does this history lesson have to do with me?” But these are not esoteric questions. If our Lord Jesus Christ was not a real man, if he was merely a projection of God into this world from another, then we are not truly saved. Look at it this way:

There's a new Star Wars movie out now. I haven't seen it, and I don't go to theaters, so I won't get to see it until it's on cable; but, if you can think back to the first Star Wars movie, you'll remember that whenever Darth Vader wanted to talk to the Emperor, he would use this communication device, and the Emperor's image would appear in 3-D like a hologram, but the Emperor wasn't really there; it was just a projection.  That's exactly what the Nestorians believed Jesus was: God didn't really come to earth in the flesh; He was just a projection of God in the appearance of man, beamed onto this earth, if you will, by some kind of divine 3-D projector. That's exactly what the Nestorians believed Jesus was: God didn't really come to earth in the flesh; He was just a projection of God in the appearance of man, beamed onto this earth, if you will, by some kind of divine 3-D projector.

Now, just to be fair, like most heretics, the Nestorians came up with this not out of malice, but out of their love for God: they so venerated God's Divinity that they considered the idea of a real incarnation an insult to God; they came up with a way to explain it away in order to protect the idea that God cannot be diminished in any way. But the implications of this are devastating: if Jesus wasn't a real man, then His suffering wasn't real, He didn't really die so there was no reason for Him to actually rise, which means, of course, that the penalty for the Original Sin is not paid and we are not saved. The crux of the problem for the Nestorians was the scandal of the notion that God could die, something they reasoned could not happen; therefore, Jesus could not have been fully man; he might have been “human” in some sort of ethereal, poetic way, but He couldn't have been a real flesh and blood man like the rest of us.

Like most of the early heresies, Nestorianism was fueled by an extreme and enthusiastic love for God without fully thinking it through, and that thinking through took centuries. A century earlier, Arius, whom we've mentioned before, tackled the same problem from the opposite extreme, declaring not that Jesus wasn't a real man, but that He wasn't really God. In both cases, the passion, death and resurrection of our Lord becomes nothing but a puppet show: there's no real suffering or death, no real resurrection, so no one is actually redeemed.

When finally the issue was settled, at least officially, the Church resolved that no such free thinking should be allowed to infect the Church again, which is how we got the Creed, and why we are all required, each and every Sunday, to declare publicly that Jesus Christ is “consubstantial with the Father; through Him all things were made. For us men and for our salvation He came down from heaven, and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and became Man.”  Not a symbol of a man, not a projection of a man, not merely in the form of a man, but a real flesh and blood Man: a Man with two natures, fully human and fully divine, existing in the same single Person; a Man Who suffered and died to pay the debt of Original Sin, and Who, by His own divine power, rose from the dead and redeemed His fellow men. Not a symbol of a man, not a projection of a man, not merely in the form of a man, but a real flesh and blood Man: a Man with two natures, fully human and fully divine, existing in the same single Person; a Man Who suffered and died to pay the debt of Original Sin, and Who, by His own divine power, rose from the dead and redeemed His fellow men.

Thus endeth the history lesson. Not to suggest that any of us are tempted to lapse into Nestorianism;—or Arianism, for that matter—but, the fore-thinking Evangelist Matthew understood the danger of not understanding the true nature of our Blessed Lord correctly, which is why he began his Gospel they way he did.

Back on the Feast of Christ the King, the very Sunday before Advent began, I had told you that, if it had been up to me (which it isn’t), I would have chosen as the Gospel lesson for that day the passage from Luke chapter four, in which our Lord returns to his adopted home town of Nazareth and preaches his first homily. He chose to base his homily on the beginning of chapter 61 of the Prophet Isaiah, the very same lesson that is provided as our first lesson today…

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me; he has anointed me, and sent me out to preach the gospel to the poor, to restore the broken-hearted; to bid the prisoners go free, and the blind have sight; to set the oppressed at liberty, to proclaim a year when men may find acceptance with the Lord, a day of retribution (Luke 4: 18-19 Knox).

…and these words of the Prophet, read by our Lord in the synagogue that day, describe all of us, don’t they? For we are poor, probably materially, but certainly spiritually; we are prisoners of our egoism and our sins; we are all blind because our sins have blinded us to the beauty of the Divine Light, and are prisoners by attachment to the things of this world, and the pursuit of gratification in created things has left us brokenhearted.

Sounds dire, doesn’t it? But that is why we rejoice on this day: because the promise of the prophets was fulfilled when our real God, without losing any of His Divinity, humbled Himself to become a real flesh and blood Man, walked among us, taught and healed us, and willingly took upon Himself the burden of our sins and died for us, paying the penalty that we rightly should have paid, allowing grace and redemption to be ours at His expense. That is the great mystery that we now prepare to greet in little more than a week.

When he had finished reading from Isaiah that day, our Lord told the congregation in the synagogue, “This scripture which I have read in your hearing is to-day fulfilled” (v. 21 Knox). Whether it's fulfilled in our hearing depends entirely on us. There is Jesus, offering us a new life. Today, on this Gaudete Sunday—this day of anticipation and rejoicing—this offer is made to us. And even if we have squandered it many times over the years, he renews the offer to us again; this year can still be for us a year of Grace with the Lord. We don't know if this will be the year we persevere; but at least, as Christmas and a new Year approaches, we are offered another chance to try again.

Saint Luke says, “Then he shut the book, and gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. All those who were in the synagogue fixed their eyes on him” (v. 20 Knox). Let our promise to our Lord be that, filled with hope, we will begin today to keep our eyes fixed on Him.

Gaudéte in Dómino semper! “Rejoice in the Lord always: again I say, rejoice … Have no anxiety, but in everything, by prayer let your petitions be made known to God.”

* The Greater Antiphons sung at Vespers, known as the "O Antiphons," and also serving as the verse before the Gospel in the ordinary form, are ordered and utilized differently between the two forms of the Roman Rite. The banners at the top of the pages for the Days of the Greater Antiphons have been created to reflect the original ordering of the antiphons as used in the extraordinary form. For reference, the usages of the two forms compare thus:

| Date: |

Extraordinary Form: |

Ordinary Form: |

| Dec. 17. |

O Sapientia. |

O Sapientia. |

| Dec. 18. |

O Adonai. |

O Adonai. |

| Dec. 19. |

O Radix Iesse. |

O Radix Iesse. |

| Dec. 20. |

O Clavis David. |

O Clavis David. |

| Dec. 21. |

O Oriens. |

O Emmanuel. |

| Dec. 22. |

O Rex Gentium. |

O Rex Gentium. |

| Dec. 23. |

O Emmanuel. |

O Rex Gentium. |

| Dec. 24. |

[The Vigil of Christmas.] |

O Oriens. |

Regarding December 24th: in the Roman Rite, the concept of a vigil differs completely between the ordinary and extraordinary forms. In the ordinary form, a vigil is simply a celebration of the feast the evening before, either prior to or following First Vespers (in the United States, after 4:00 PM). On Solemnities on which an obligation has been attached, this may be fulfilled at either the Mass of the vigil the evening before, or on the feast itself.

In the extraordinary form, the word “vigil” designates the entire day before a First Class Feast, and the Mass for the vigil takes place in the morning. If a feast carries an obligation, this must be satisfied on the feast itself; the extraordinary form does not offer the opportunity to satisfy an obligation on the evening before.

In the extraordinary form, December 24th is the Vigil Day of Christmas and has its own proper texts, the Days of the Greater Antiphons having concluded on the 23rd. In the ordinary form, the morning of December 24th is a day of the Greater Antiphons up to Vespers, at which point it becomes the vigil for Christmas.

** "Soul of Christ, sanctify me. Body of Christ, save me. Blood of Christ, inebriate me. Water from Christ's side, wash me. Passion of Christ, strengthen me. O good Jesus, hear me. Within Thy wounds hide me. Suffer me not to be separated from Thee. From the malicious enemy defend me. In the hour of my death call me. And bid me come unto Thee. That I may praise Thee with Thy saints and with Thy angels. Forever and ever. Amen."

|