It is in the Response to Tragedy that the Characters of the Grace-filled and the Godless are Distinguished.Col. 3:4-11;

Luke 14:16-24.* The Sunday of the Forefathers of Our Lord, also known as the Sunday of the Patriarchs. The 11th Sunday after the Holy Cross. The Holy Prophet Haggai.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

1:53 PM 12/16/2012 — This Sunday of the Forefathers of Our Lord, sometimes called the Sunday of the Patriarchs, is one of two Sunday celebrations in preparation for Christmas unique to the calendar of the Byzantine Churches, the other being next week's Sunday of the Ancestors of Our Lord, also called the Sunday of the Genealogy, since on that Sunday the genealogy of Our Lord from St. Matthew is read.

Liturgically, the Gospel lessons for these two Sundays point directly to the fact the Jesus is the Messiah for which the Jews had been waiting for 2000 years. Today’s Gospel is the famous one of the Banquet, to which those who were invited (meaning the Hebrew people) were not worthy to enter, opening the banquet to the gentiles (meaning the rest of us), and thus making salvation possible for everyone; and, the fact that today's commemoration occurs on the Sunday following such a great tragedy as the one we experienced the other day is a circumstance that cannot be ignored.  The tragedy, of course, raises a host of questions that most of us realize simply cannot be answered on this side of the grave, the biggest one being: why does God allow terrible things to happen to the innocent? As people of faith, we don't wrestle with such seminal questions as much as godless people do, but that doesn't make living with them any easier. It's interesting to watch media people, who typically have no frame of reference to deal with faith, interview parents and relatives and neighbors who are people of faith, and try to process what they hear; and, it's a good opportunity to reflect on how this relates to our preparation for celebrating the birth of Our Lord. The tragedy, of course, raises a host of questions that most of us realize simply cannot be answered on this side of the grave, the biggest one being: why does God allow terrible things to happen to the innocent? As people of faith, we don't wrestle with such seminal questions as much as godless people do, but that doesn't make living with them any easier. It's interesting to watch media people, who typically have no frame of reference to deal with faith, interview parents and relatives and neighbors who are people of faith, and try to process what they hear; and, it's a good opportunity to reflect on how this relates to our preparation for celebrating the birth of Our Lord.

People for whom faith is a stumbling block like Christmas; it's their favorite Holy Day; maybe that's the reason some of them come to church only on that day. Christmas presents to us a very non-demanding side of Christianity. A Baby in a manger is a much more acceptable God to the worldly: he is small and weak, cute and beautiful, undemanding and nonthreatening. What a panacea religion can be when we can picture our God as being perpetually in diapers!

But the Advent of the incarnation—the birth of our Lord, the Baby in the manger—is a historical event. It happened in the past and is now over. It will not happen again. We can kneel before the manger scene and pray to the Baby, if that makes us feel better; but, the one who hears those prayers is not a Baby any longer. He is a man, he is God, he is the one who hung on the Cross, he is the one who rose from the dead and who sits at the right hand of the Father. And even if we choose to cling to a comfortable image of him helpless in a manger, he does not view the world now through a baby's eyes. And neither should we.

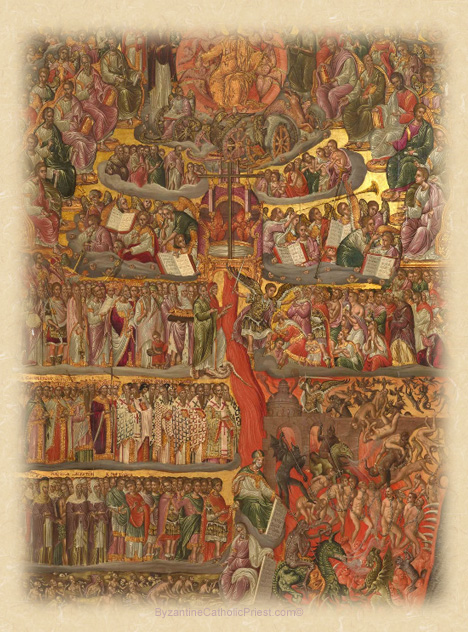

While they may sound strange at first, there are two different reasons why the tragedy of the other day disturbs us so much: one, of course, is the genuine sorrow we feel for the parents of the children who were lost, to be sure; but, another, which we might be reluctant to admit, is the realization that, if the Lord can allow innocent children to be taken so suddenly and in such a horrible way, then any of us can be taken at any time. It's a twist on the “non-church-goer-at-a-funeral” phenomenon: you can always tell the non-church-goer at a funeral because he doesn't know how to react publicly to someone's death, always fidgeting in the pew and looking around, never making eye-contact, or trying to mask his sense of awkwardness by gregariousness and out-of-place humor. Like a funeral in the family, the tragedy of the other day is another one of those occasions which forces the subject of death before us, and in a way that confounds the notion of fair play on which the social and political parameters of our society are based. Our sorrow and grief give way to anger, not simply because the tragedy in the news is so unfair, but because, subconsciously, it reminds us that our own judgment will be just as leveling. Our final judgment, at least as it is described by Our Lord, will not be based on the media culture's interpretation of justice or fairness, with an emphasis on our good intentions; it will be based on the cold, raw data of what we did or what we didn't do; and that, in fact, is the very subject that these two Sundays before Christmas—the Sunday of the Forefathers and the Sunday of the Ancestors—force before us.

How we respond to that confrontation is crucial; it compels each of us to ask the question: what does my faith in Christ really mean to me personally? Is it just a "touchy-feely" philosophy of life, or is it something that has implications for my final end, for the final disposition of my soul after death, something which is symbolized not so much by a Baby in a manger but by a Man on a cross?

It is at least comforting to know that we have a frame of reference in which to process the tragedy we've just witnessed on the news, even though it remains a hard thing to deal with; but, think of the millions in our society who have no frame of faith to picture such events as these. How do they process it in a meaningful way? Do they not immediately try to slake their sense of abandonment by scrambling after some lame, social-political solution like gun control or a draconian public health mandate that would round up and incarcerate anyone who acts oddly? We've heard both in the last two days. That's why I thought that Mr. Huckabee's comment which made so many people angry—that the tragic events are the indirect result of a school system without God and a society without faith—were right on target.

It was interesting to go on Facebook yesterday and see the sharp division between the posts left by people of faith and those left by people without faith: the people without faith wasted no time calling for political action; the people of faith simply asked for and promised their prayers, which is what we should be doing right now, so we will leave this subject behind. But it is the Sunday of the Forefathers which thrusts the very themes of death and judgment before us; and, on such a Sunday is it not inappropriate to use the lesson of a great tragedy to assist our meditation on our own mortality, on the need for repentance, and to renew our devotion to Christ through prayer, penance and confession, so that we can approach the celebration of the birth of another Child who died, whose very purpose for coming into our world was to die for us.

Father Michael Venditti

* The two Sundays before the Nativity of our Lord are not part of the cycle of Sundays after Pentecost, and bear directly on our preparation to celebrate the coming of the Savior, with an emphasis on the analogous relationship between that preparation and contemplation of our Final Judgment. They are named for the human forebears of our Lord by blood relationship to his foster father, Joseph, which are divided into two halves. This Sunday, called the Sunday of the Forefathers or the Sunday of the Patriarchs, uses the Gospel ordinarily indicated for the 28th Sunday after Pentecost, which is why the Gospel on that day was replaced by another. The Apostolic reading, likewise, is always the

one ordinarily indicated for the 29th Sunday after Pentecost, though it is simply repeated today.

Next Sunday, called the Sunday of the Ancestors, is marked by the reading of the complete first chapter of Matthew's Gospel, in which the genealogy of our Lord is recorded in detail.

In some traditions, it is customary to read these readings as well as those that would be prescribed if one was still following the post-Pentecost cycle. That was not done in our two parishes this year.

The Advent tradition of the Latin Church observes a similar custom, albeit in reverse, distinguishing the first part of the season from that after December 17th by switching from a consideration of the Second Coming to a more specific perparation for Christmas, though the distinction between the two parts of Advent is not as sharply noticed now as in previous times (for example, the wearing of rose colored vestments marking the change is now optional). It is an example of the polity that existed between the liturgical customs of East and West that was evident in the liturgy prior to the reforms following the Second Vatican Council.

|