Something New, Something Old.Colossians 3:4-11;

Luke 14:16-24. The Sunday of the Forefathers. The Holy Martyr Eleutherius. Our Venerable Father Paul of Latra. Our Holy Father Stephen, Archbishop of Surozh.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

12:27 PM 12/15/2013 — I know that, last week, I said we were to be done with St. Paul because of the important nature of the two pre-Nativity Sundays, and that's true; but, if you will allow me this one last little bit from Colossians, which is always read on the Sunday of the Forefathers: it consists of the verses that immediately precede the ones read last week, and I just feel compelled to share with you Msgr. Knox's translation:

You must deaden, then, those passions in you which belong to earth, fornication and impurity, lust and evil desire, and that love of money which is an idolatry. These are what bring down God’s vengeance on the unbelievers, and such was your own behaviour, too, while you lived among them. Now it is your turn to have done with it all, resentment, anger, spite, insults, foul-mouthed utterance; and do not tell lies at one another’s expense. You must be quit of the old self, and the habits that went with it; you must be clothed in the new self, that is being refitted all the time for closer knowledge, so that the image of the God who created it is its pattern. Here is no more Gentile and Jew, no more circumcised and uncircumcised; no one is barbarian, or Scythian, no one is slave or free man; there is nothing but Christ in any of us (Col. 3:5-11).

And you can see how this passage fits so well with the Gospel for the Sunday of the Forefathers, which is the Parable of the Wedding Banquet, in which “none of those who were first invited shall taste of my supper” (Luke 14:24). This Gospel occurs more than once in the course of the year, and we've looked at it before. And you can see how this passage fits so well with the Gospel for the Sunday of the Forefathers, which is the Parable of the Wedding Banquet, in which “none of those who were first invited shall taste of my supper” (Luke 14:24). This Gospel occurs more than once in the course of the year, and we've looked at it before.

Ronald Knox himself was an extremely interesting man. He was born in 1888, the son of the Anglican Bishop of Manchester, and was a brilliant scholar from the start. At the tender age of twenty-four he became the Anglican chaplain of Oxford's Trinity College, but resigned in 1917 to enter the Catholic Church, and was quickly ordained to the Holy Priesthood. He returned to Oxford as a Catholic chaplain, and supplemented his meager income by writing detective stories. In 1939 he was commissioned by the Catholic bishops of England and Wales to provide a new translation of the Bible into English to replace the antiquated Challoner-Rheims Bible, an 18th Century update to the Douay-Rheims Bible completed in France in 1609 by expatriate English Catholics who had fled their country because of religious persecution; but, because the Douay-Rheims and Challoner-Rheims had become so ingrained in the minds of English speaking Catholcs around the world for hundreds of years, there was a lot of resistance to the idea of a new translation, and Knox was forced out of Oxford and went into seclusion at the estate of two prominent Catholic converts, Lord and Lady Aston, where he finally completed the translation in 1948. The bishops of England and Wales were so pleased with it that they authorized its use in the Churches of Great Britain. Unfortunately, the bishops of the United States had begun their own, vastly inferior revision of the Challorner-Rheims Bible around the same time,* and Knox's Bible never took hold in this country, and was out of print for a long time. I got mine in a used book store in London, printed in 1963; but, thankfully, a brand new, beautifully bound edition of it was published just this year. It's a little expensive but, if you're interested I can give you the address of the web site where you can order one.**

So much for that. Let's turn now to the topic of the day, the Sunday of the Forefathers.

As you know, Phillips Fast is so called simply because it begins on the day after the feast of the Apostle Philip, and is actually two weeks longer than the Roman Catholic season of Advent to which is corresponds. The idea of a pre-Christmas fast is one of the few Christian liturgical traditions that began in the West rather than in the East. We know that it was observed in Rome by Pope St. Gregory the Great toward the end of the Sixth Century, and doesn't appear in the Churches of the Byzantine rite until the Ninth Century. Even so, the way we observe it now didn't take shape until the Seventeenth Century, around the same time that our own Ruthenian Church came into union with Rome. And even though Phillips Fast is more than two weeks longer than it's Roman Catholic counterpart, it seems to pass very quickly, probably because it’s observed in such a subtle way. The Altar coverings are changed to a penitential color, and fasting recommendations are made for the season; but, other than that, Phillip’s Fast is simply announced. There’s nothing done liturgically to mark its arrival: no special prayers are added to the Liturgy, no Advent Candles are lit as in the Latin Church, or anything like that. It's just “Welcome to Phillips Fast and have a happy day.”

But, at the end of the season there are two Sundays which are of very ancient origin, and which touch directly on our preparation for celebrating the Nativity of our Lord: the Sunday of the Forefathers, which we celebrate today, sometimes called the Sunday of the Patriarchs; and the Sunday of the Ancestors of our Lord, also called the Sunday of the Genealogy, since on that Sunday the genealogy of Our Lord from St. Matthew is read.

The Gospel lessons for these two Sundays point directly to the fact the Jesus is the Messiah for which the Jews had been waiting for two thousand years. Today’s Gospel, the familiar one of the Wedding Banquet, is an allegory for salvation history, explaining how salvation is made possible for everyone by Christ. And one could say that it’s a message destined to fall on deaf ears, given everything that competes to occupy our attention this time of year.  It’s ironic that the way Christmas and the preparation for it has morphed in modern times makes this the one time of year when we probably think about our faith the least, not out of indifference, but simply because there are so many other things we’ve convinced ourselves we have to worry about. And that’s a great shame, because the real message of the Church in this time of year is a vital one: when we celebrate the Nativity of our Lord, we do not simply commemorate the historical event of the coming of our Lord in the manger; many of the Gospel lessons directly following the Nativity present our Lord's instructions concerning the end times, the final judgment, repentance from sin. The Advent that we celebrate is not just a historical one;—not just the coming of Christ in the manger—it's the Advent of Christ the King, when our Lord, who once came humbly in a cave, will come again gloriously as the judge and ruler of the universe, when all of history will be brought to its completion, when the righteous will be separated from the unrighteous, when good will win its final victory over evil, and when the gates of heaven and hell will be shut forever; when all for which this world has prepared us will come to pass, and time itself will be no more. You can see now, I hope, how all these Apostolic readings from St. Paul, over which we've been obsessing the last four weeks, roiling about the Devil, are relevant to this message. It’s ironic that the way Christmas and the preparation for it has morphed in modern times makes this the one time of year when we probably think about our faith the least, not out of indifference, but simply because there are so many other things we’ve convinced ourselves we have to worry about. And that’s a great shame, because the real message of the Church in this time of year is a vital one: when we celebrate the Nativity of our Lord, we do not simply commemorate the historical event of the coming of our Lord in the manger; many of the Gospel lessons directly following the Nativity present our Lord's instructions concerning the end times, the final judgment, repentance from sin. The Advent that we celebrate is not just a historical one;—not just the coming of Christ in the manger—it's the Advent of Christ the King, when our Lord, who once came humbly in a cave, will come again gloriously as the judge and ruler of the universe, when all of history will be brought to its completion, when the righteous will be separated from the unrighteous, when good will win its final victory over evil, and when the gates of heaven and hell will be shut forever; when all for which this world has prepared us will come to pass, and time itself will be no more. You can see now, I hope, how all these Apostolic readings from St. Paul, over which we've been obsessing the last four weeks, roiling about the Devil, are relevant to this message.

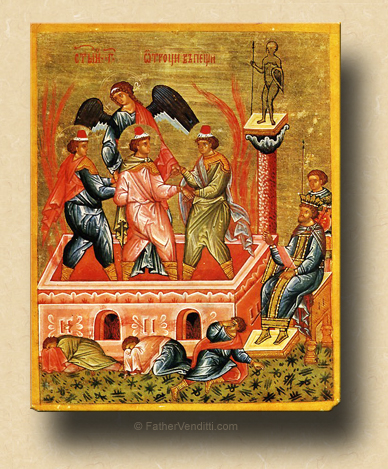

But who exactly are the Patriarchs, the “Forefathers of our Lord” as this Sunday calls them; and, why do we commemorate them? The question is rooted in the fact that most of us have lost touch with the Old Testament. Even when we try to read it, which is rare, some of it doesn't seem to make a lot of sense. But the Fathers of the Church of the first three centuries, whose lives and writings are so much responsible for the spirituality of the Eastern Churches today, had an intimate relationship with the Old Testament. They saw Jesus Christ present in it in an allegorical way. They saw the Sacrifice of Issac by Abraham as the Father sending his Son to be sacrificed for the redemption of man; they saw Abel, slain by Cain, as the first martyr and the good shepherd who lays down his life for his sheep; they saw Jacob as the model of patient service and conversion, Joseph as the image of one unjustly accused, and the suffering servant described by Isaiah as Christ himself in his passion and death; and on and on and on. For the Fathers, every word of the Old Testament points to Christ, and makes the whole of the New Testament understandable. You may also have noticed that many of the chants for the Liturgy of this day refer to the three young men of the Book of Daniel, who are thrown into the furnace for refusing to worship the image of King Nebuchadnezzar;—you'll hear them mentioned in the Ambon Prayer at the end of the Liturgy—their feast falls on December 17th, very close to Christmas for obvious reasons, reminding us that, in spite of the cute and consoling traditions surrounding the image of the baby Jesus in the manger, following Christ is a matter of sacrifice. The New Testament example of this is given right after Christmas on the feast of St. Stephen. In both cases, those being sacrificed are comforted by a miraculous appearance of an angel, just like our Lord in the Garden.

Next Sunday's Gospel is the entire first chapter of St. Matthew, in which the human genealogy of our Lord is read, bringing home the nature and implications of the incarnation in a less allegorical and even more graphic way. For now, it should be enough for us to consider the truth of everything that St. Paul has been telling us during this season of Phillips Fast: he sums it up in the very first line of today's Apostolic reading, reminding us of what our real focus should be as we prepare to mark the birth of our Savior: “Christ is your life, and when he is made manifest, you too will be made manifest in glory with him” (Col. 3:4).

* The official title of this American translation was the Confraternity Version. It's name was taken from the “Confraternity of Christian Doctrine,” which was the catechetical wing of the National Catholic Welfare Conference, precursor of the old NCCB and the present USCCB. It was never published as a single volume including both Old and New Testaments. The most common edition of it included the Confraternity version of the New Testament paired with the Old Testament of the Challoner-Rheims. Before the Old Testament was completed, the New Testament was already being revised further into what would become the New American Bible. Even so, the Confraternity New Testament, which was the official version read in American churches for a brief time, was nothing to write home about, being little more than the Challoner-Rheims with the “thee's, thou's and thine's” removed.

** One of the misconceptions about Msgr. Knox's translation is that it is a straight translation of the Latin Vulgate and not of the original texts, a misconception for two reasons: (1) there are no original texts, as the various extent Greek and Hebrew manuscripts differ from one another even more than any one of them differs from the Vulgate; and, (2) Msgr. Knox had all the existing Greek and Hebrew texts at his elbow while doing his work, and always leaves a footnote giving all the various renderings and where they come from, something that very few of the more modern versions bother to do.

|