Hand-Wringing is Never an Appropriate Posture for Prayer.

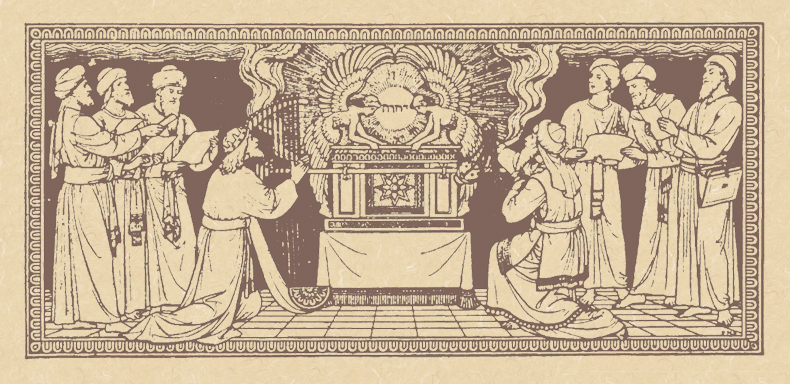

The Memorial of Saint John of the Cross, Priest & Doctor of the Church.

Lessons from the feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 41: 13-20.

• Psalm 145: 1, 9-13.

• Matthew 11: 11-15.

|

…or, from the proper:

• I Corinthians 2: 1-10.

• Psalm 37: 3-6, 30-31.

• Luke 14: 25-33.

…or, any lessons from the common of Pastors or the common of Doctors of the Church.

|

The Second Thursday of Advent.

Lessons from the dominica,* according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Romans 15: 4-13.

• Psalm 49: 2-3, 5.

• Matthew 11: 2-10.

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:07 AM 12/14/2017 — I’m not going to rehash what’s been said many times in this chapel about Saint John of the Cross who, together with Saint Teresa of Jesus—or, as many people refer to her, Teresa of Avila—instituted a general reform of the Carmelite Order, ultimately founding the Carmelites of the Strict Observance, commonly called the Discalced Carmelites, discalced meaning “without shoes” because they wear sandals. Known together as the Spanish Mystics, their approach to prayer was suspect for a long time in the Church because it departed dramatically from the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius, and really didn’t come into its own until the election of Pope Saint John Paul II, who was introduced to their writings as a young man, setting him on the path of pursuing the Holy Priesthood. 9:07 AM 12/14/2017 — I’m not going to rehash what’s been said many times in this chapel about Saint John of the Cross who, together with Saint Teresa of Jesus—or, as many people refer to her, Teresa of Avila—instituted a general reform of the Carmelite Order, ultimately founding the Carmelites of the Strict Observance, commonly called the Discalced Carmelites, discalced meaning “without shoes” because they wear sandals. Known together as the Spanish Mystics, their approach to prayer was suspect for a long time in the Church because it departed dramatically from the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius, and really didn’t come into its own until the election of Pope Saint John Paul II, who was introduced to their writings as a young man, setting him on the path of pursuing the Holy Priesthood.

Last Sunday's Gospel lesson focused our attention on John the Baptist, and in today's lesson our Lord Himself comments on His Forerunner, identifying him with the greatest of the Old Testament prophets, Elijah.

We often make the mistake of thinking that there is this wide, temporal gulf between the Old and New Testaments. Certainly the five Books of Moses and the histories of the Kings of Israel present events that were thousands of years before the birth of our Lord, but the events of the Old Testament span a vast period of time; the last of the books written in the Old Testament, the two Books of Maccabees, are generally believed to have been written piecemeal between a few hundred years before Christ up to less than sixty years before, including the beginnings of the Roman occupation; and, if you remember from a few previous homilies, you might recall that this was about the time that a new party of progressive rabbis began to appear on the scene called the Pharisees, preaching a resurrection from the dead and introducing a number of innovations to Jewish life, including the synagogue service in which our Lord regularly participated, which explains our Lord's strained relationship with the traditionalist wing of the rabbinical class, known as the Sadducees, who neither believed in a resurrection from the dead nor a synagogue service. So, the transition from one Testament to the other is seamless, and the revolt of Judas Maccabeus, who was clearly a resurrection-believing Pharisee, was still relatively fresh in the minds of the Jewish people of our Lord's time; there may even have been some old timers in the time of our Lord who were alive during that revolt, which culminated with the expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple and its rededication, an event which is commemorated by the Jews every year in the festival known as Hanukkah.

When our Lord refers to the Baptist as Elijah in today's Gospel lesson, He's further cementing the relationship between the two Testaments, and Catholic Biblical theology has traditionally regarded John the Baptist as the last of the Old Testament prophets, even though he appears at the beginning of the New; and, the first chapter of Matthew's Gospel, which, according to the Fathers of the Church, was the first Gospel to be completed, is sometimes regarded as the last book of the Old Testament, recounting the human genealogy of our Lord from Abraham up to Joseph, the husband of Mary.**

Of course, in your Bible at home, the distinction between the two is obvious: you turn the last page of the Old Testament, and there's enormous print that says, “THE NEW TESTAMENT”; but, that distinction is, from a purely historical perspective, artificial. Very little time passes between the end of Second Maccabees and the preaching of John the Baptist. In fact, there's more time between the Epistles of Saint Paul, composed shortly after the Ascension of our Lord, and the Gospel of Saint John, which is written a considerable time after the Ascension.

And while Divine Revelation, properly so called, ends with the Apocalypse of Saint John, commonly called today the Book of Revelation, salvation history continued through the writings of those men whom we refer to as the Fathers of the Church, who were the direct successors of the Apostles, made bishops by the Apostles themselves, who, along with their own direct successors, were responsible for our Church's most important theological developments in the first three hundred years after Christ. It is not a coincidence that, during this Advent season, the feast days of many of these men are celebrated, Pope Saint Damasus, whom we commemorated the other day, being one of them. Some of them are mentioned by name in the Roman Canon, which is why I will occasionally use it during this season. And it was during this period that the Church, in response to the many heresies that sprung up over the years, composed the first creeds, statements of faith designed to clarify and codify exactly what someone had to believe if he wanted to call himself a Christian.

The questions and challenges that the Church was facing during these early years wouldn't have made any sense to the Apostles themselves: questions regarding the relationship between the human and divine in the person of Christ, about the nature of the resurrection and when Christ would come again, about whether the incarnation was real or just an appearance of God on earth, about whether the veneration of holy images violated the Old Testament commandment against idolatry, even about whether it was legitimate to transfer the sabbath from Saturday to Sunday.  The Church was split up many times over these questions, and sometimes for hundreds of years. More than once there were times when no one was quite sure who was the pope in Rome; in fact, when Cardinal Roncalli was elected Pope in 1958, he chose the name John XXIII in order to settle a dispute from five hundred years earlier, when there were two popes elected by two competing conclaves, one in Rome and one in France. The one in Rome called himself John XXIII, but his election was marred by political intrigue, and some of the cardinals fled to France to elect another. When Roncalli was elected and took the name John, and someone called him John XXIV, he corrected him and said, “No, I'm John XXIII,” settling a dispute that had been left unanswered for five hundred years. The Church was split up many times over these questions, and sometimes for hundreds of years. More than once there were times when no one was quite sure who was the pope in Rome; in fact, when Cardinal Roncalli was elected Pope in 1958, he chose the name John XXIII in order to settle a dispute from five hundred years earlier, when there were two popes elected by two competing conclaves, one in Rome and one in France. The one in Rome called himself John XXIII, but his election was marred by political intrigue, and some of the cardinals fled to France to elect another. When Roncalli was elected and took the name John, and someone called him John XXIV, he corrected him and said, “No, I'm John XXIII,” settling a dispute that had been left unanswered for five hundred years.

It is a fact that our historical perspective begins on the day of our birth. It is very difficult for those who do not know history to keep things in perspective. We look at the Church today and wring our hands; we agonize over priests and bishops who preach heresy, and may even find ourselves, in an unguarded moment, becoming angry even at the Holy Father, and say to ourselves, “It's never been this bad.” Believe me, it's been this bad; in fact, it's been much worse, and the Church has always emerged facing forward.

More than any other season of the year, Advent presents to us the continuity of salvation history. “Jesus Christ, yesterday, and today; and the same for ever” (Heb. 13: 8 Douay-Rheims). Or, as today's Responsorial Psalm proclaims, “Your Kingdom is a Kingdom for all ages, and your dominion endures through all generations” (Psalm 145: 13 RM3).

* In the extraordinary form, on ferias outside privileged seasons, the lessons come from the previous Sunday.

** This statement is not held by those who continue to accept the now discredited "two source theory," which posits that the Gospels of Matthew and Luke were compiled using material from Mark's Gospel and some unknown document which they identify as "Q". This theory is based solely on the presumption that the Gospel which appears to be the shortest and most primitive, i.e., Mark, must be the first, and whatever is common in Matthew and Luke but not found in Mark must come from some source not yet discovered or no longer extent. By the same reasoning, an archaeologist a thousand years from now, finding both a copy of Gone with the Wind and a "Reader's Digest" version of the same, would have to assume that the condensed version was the original, and the longer, more embellished one was a later redaction.

While the earliest extent manuscript of Matthew's Gospel is a Greek translation, it is clear that the original was written in Aramaic. St. Papias, in the second century, testified that "Matthew put together the oracles [of the Lord] in the Hebrew language, and each one interpreted them as best he could"; likewise, St. Irenaeus tells us: "Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome and laying the foundations of the church," then proceeds to quote from it.

|