Confession, Part Two: It's Not a Water Sport.

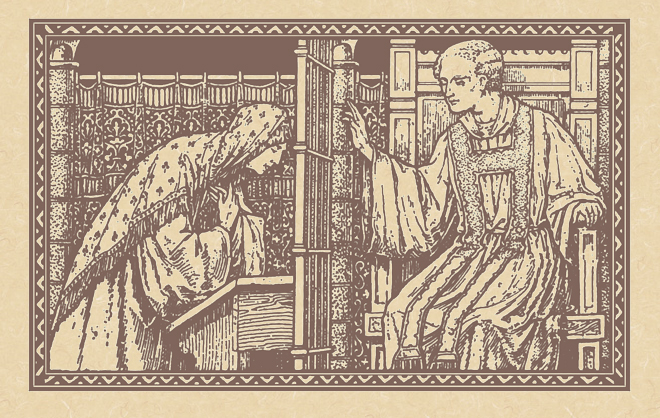

The Third Sunday of Advent, known as "Gaudete Sunday."

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Zephaniah 3: 14-18.

• Isaiah 12: 2-6 (in place of the psalm).

• Philippians 4: 4-7.

• Luke 3: 10-18.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Philippians 4: 4-7.

• Psalm 79: 2-3, 2.

• John 1: 19-28.

The Sunday of the Forefathers;* the Feast of the Holy Martyrs Eustratius, Auxentius, Eugene, Mardarius & Orestes; and, the Feast of the Holy Virgin & Martyr Lucy.

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Colossians 3: 4-11.

• Luke 14: 16-24.

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:26 AM 12/13/2015 — Gaudéte in Dómino semper: íterum dico, gaudéte. Dóminus enim prope est. “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I say, rejoice. Indeed, the Lord is near” (RM3). Of course, it's the Entrance Antiphon from which the Third Sunday of Advent takes its traditional name of “Gaudete Sunday,” and it's from Saint Paul. The Introit for the traditional Latin Mass is the same, but actually continues one verse further, and may be more meaningful for some of us: “Rejoice in the Lord always: again I say, rejoice. Let your moderation be known to all men: for the Lord is near. Have no anxiety, but in everything, by prayer let your petitions be made known to God” (Phil. 4: 4-6 RM 1962), which is, in fact, our second lesson today from Philippians. The other lessons, too, reflect this spirit of joy and rejoicing: the Prophet Zephaniah exhorts us: “Shout for joy, O daughter Zion! Sing joyfully, O Israel! Be glad and exult with all your heart, O daughter Jerusalem! The Lord has removed the judgment against you …” (3: 14-15 RM3); and, after hearing the command of repentance from John the Baptist, Saint Luke reports to us that “… the people were filled with expectation …” (3: 15 RM3). Of course, in both Philippians and the preaching of the Baptist, this joy and expectation is directly linked, as you can plainly see, to the idea that the coming of Christ will mean only one thing: repentance and the forgiveness of sins. 9:26 AM 12/13/2015 — Gaudéte in Dómino semper: íterum dico, gaudéte. Dóminus enim prope est. “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I say, rejoice. Indeed, the Lord is near” (RM3). Of course, it's the Entrance Antiphon from which the Third Sunday of Advent takes its traditional name of “Gaudete Sunday,” and it's from Saint Paul. The Introit for the traditional Latin Mass is the same, but actually continues one verse further, and may be more meaningful for some of us: “Rejoice in the Lord always: again I say, rejoice. Let your moderation be known to all men: for the Lord is near. Have no anxiety, but in everything, by prayer let your petitions be made known to God” (Phil. 4: 4-6 RM 1962), which is, in fact, our second lesson today from Philippians. The other lessons, too, reflect this spirit of joy and rejoicing: the Prophet Zephaniah exhorts us: “Shout for joy, O daughter Zion! Sing joyfully, O Israel! Be glad and exult with all your heart, O daughter Jerusalem! The Lord has removed the judgment against you …” (3: 14-15 RM3); and, after hearing the command of repentance from John the Baptist, Saint Luke reports to us that “… the people were filled with expectation …” (3: 15 RM3). Of course, in both Philippians and the preaching of the Baptist, this joy and expectation is directly linked, as you can plainly see, to the idea that the coming of Christ will mean only one thing: repentance and the forgiveness of sins.

Which is very convenient for us since, as you know, these Advent Sunday homilies are all being devoted to the subject of confession. We embarked on this course at the beginning of this season because it marks the beginning of the Jubilee Year of Mercy. We look forward to the opening of our own Holy Door on the Sunday after Christmas, which will offer us the opportunity to receive the plenary indulgence associated with this special year; but, one of the three conditions for receiving that indulgence is that one must make a complete and sincere confession. We began last week by looking at the parable of the Good Samaritan, in which a rabbi had asked our Lord a question about right and wrong, but he didn’t quite like the answer he received, so he thought he could get around it by being just a little too smart for his own good; and, of course, our Lord doesn’t let him get away with it. The point being that when we are faced with a question of right or wrong, we can try to weasel our way around it, like the rabbi did, or we can face it head on and deal with it honestly, even if it means admitting to ourselves our own shortcomings. And I concluded last week, you may remember, by telling you that confession is not a therapist’s couch but a sacrament. We don’t go there to discuss our problems with the priest; we go simply to be forgiven for what we did that was wrong.

That being said, it’s important, before going to confession, that we have some idea of what sort of things need to be said. And here I’ve found that a lot of people get very confused. We live, after all, in a very subjective society: morality is, more often than not, reduced to a question of personal conscience or—to be more precise—personal feelings, and it’s very easy to forget that, for the Christian, right and wrong are not matters of personal opinion. Sometimes I think it would be instructive for lay people to be able to spend a day hearing confessions. Of course, if you were to do that you would be immediately excommunicated for impersonating a priest in the confessional. But what you would find amazing—and what I find amazing—is that people can go to confession no more that once or twice a year and still have not much to confess. “I told a few lies, I yelled at my wife, I watched a dirty movie on the Internet.” And that could be a typical confession of someone who hasn’t been to confession in ten years. By contrast, people who go to confession regularly, like once a month, seem to have much more to confess, and are able to do it in much more detail, sometimes more detail than is needed.  And the reason for that is because the more you go to confession, the more you become sensitive to things in your life that are sinful that you wouldn’t have recognized as sinful before. It’s also the result of grace, because, after all, not only does confession forgive our sins, but it also gives us grace to resist temptation as well as grace to recognize sin in our lives. That’s why the more we confess the more we have to confess, not because we’re getting worse and worse but just the opposite: because we’re becoming more sensitive to sin in our own lives, and this is how frequent confession leads us to spiritual perfection. And the reason for that is because the more you go to confession, the more you become sensitive to things in your life that are sinful that you wouldn’t have recognized as sinful before. It’s also the result of grace, because, after all, not only does confession forgive our sins, but it also gives us grace to resist temptation as well as grace to recognize sin in our lives. That’s why the more we confess the more we have to confess, not because we’re getting worse and worse but just the opposite: because we’re becoming more sensitive to sin in our own lives, and this is how frequent confession leads us to spiritual perfection.

So, the subject matter of our confession is not subjective, it's objective. We don't decide for ourselves what we want to confess because we don't decide for ourselves what's a sin and what isn't. God does. That was the whole point of our discussion about Original Sin last Tuesday on the feast of the Immaculate Conception, for which the first lesson, from Genesis, was the fall of man: Adam and Eve eat an apple off a tree that's called what? The tree of “the Knowledge of Good and Evil.” It represents man trying to usurp the authority of God by deciding for himself what's right and what's wrong, and every sin we could possibly commit is derived from it; that's why it's called Original Sin.

So, it is very important, before making our confession, to make a good examination of conscience based on the Ten Commandments of God and the Six Precepts of the Church. Some of us can do that from memory, but a lot of us can't, especially if we haven't been to confession in a long time, so we need help. I've got some leaflets here of a very basic but good examination of conscience which I stole from the gift shop, which I will leave right here for whoever wants one; but, they also have a booklet there you can buy for next to nothing which contains the same examination of conscience along with other prayers and devotions helpful for making a good confession.

Of course, providing ourselves with a good examination of conscience isn't going to mean a whole lot if we can't convince ourselves to go to confession in the first place, which brings us to the next step in this process, which is to address why people don't go to confession as often as they should, which is what we have to talk about now.

There are, of course, a number of reasons people don't seem to go to confession as often as they used to; but, of all the reasons people may give for not going to confession, the one they never admit to is that they're afraid. Fear of confession is a very common thing, and most people who don’t go to confession regularly may not even be aware that they are actually afraid. After all, to admit that you’re a coward is not a flattering thing. So, people will often manufacture in their minds all kinds of logical rationalizations to mask from others—and from themselves—the real reason they don’t go to confession, which is that they’re terrified.

Some of these rationalizations are incredibly stupid, and if the people who make them were to actually think about them for five seconds they’d realize that. And one of the most common is: “I don’t see why I need to tell my sins to a priest. I just tell God I’m sorry directly, by myself.” Now, think about that for a minute. On the morning Jesus rose from the dead He appeared in the upper room to the eleven remaining Apostles. “[H]e breathed on them [so the Gospel says] and said to them, 'Receive the holy Spirit. Whose sins you forgive are forgiven them, and whose sins you retain are retained'” (John 20: 22-23 NABRE). The Apostles, as they spread the new religion throughout the world, laid hands on other men giving them this same power, generation after generation, all the way down to our present time. This power to forgive sins is part of the Holy Priesthood that the Church received in an unbroken line from the Apostles themselves, who received it from Christ. What’s significant about Christ’s institution of this sacrament is the phrase, “whose sins you retain are retained.”

That’s important, because what Jesus is telling the Apostles is that, if someone has sinned and wants to be forgiven, they have to come to you. If they don’t come to you, and you don’t forgive their sins, their sins are not forgiven. They can’t do it by themselves. Now, the person who tries to mask his fear of confession by saying that he doesn’t have to tell his sins to a priest and he only needs to tell God he’s sorry himself is basically saying that, after more than two thousand years of Divine Revelation, teaching and tradition, God has now given him a special privilege which He has never given to anyone else before:  the ability to have his sins forgiven without recourse to the Sacrament which Christ established for that purpose; and, that when Jesus said what He did to the Apostles, what He really meant was, “Oh, this applies to everyone except so-and-so, whom you don’t know, but who will be alive some two thousand years from now, and who will be the only person in the whole universe who won’t need to use this sacrament to have his sins forgiven.” Talk about ego! the ability to have his sins forgiven without recourse to the Sacrament which Christ established for that purpose; and, that when Jesus said what He did to the Apostles, what He really meant was, “Oh, this applies to everyone except so-and-so, whom you don’t know, but who will be alive some two thousand years from now, and who will be the only person in the whole universe who won’t need to use this sacrament to have his sins forgiven.” Talk about ego!

That’s why I said that I don’t really believe that anyone actually believes this; and when someone says, “Well, I don’t think I need to tell my sins to a priest,” what they really mean is, “I’m really scared to go to confession, but I don’t want to admit to you that I’m a spineless coward, so let me tell you this fairy tale about how I know better than Jesus Christ about how sins are forgiven.”

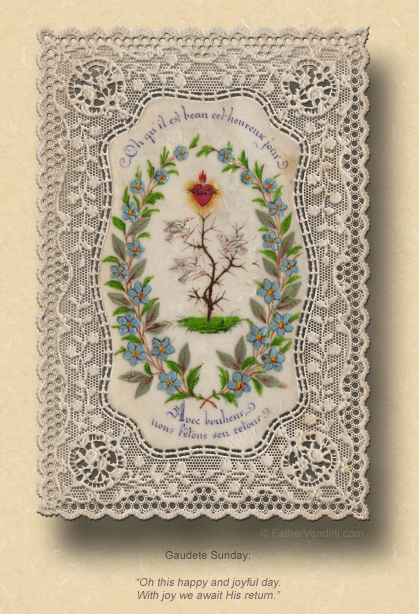

OK. Now that we’ve established that people are afraid to go to confession, let’s talk about why. For some people it may be that they had a bad experience in the confessional once, and they’re just afraid to go back. I had a bad experience as a child in confession. In fact, it was the day of my first confession. We had those old fashioned confessionals where the priest sat in between two stalls with sliding doors on the screen; so, when you went in, he was already hearing the confession of the person on the other side. And you had to kneel there in the dark and wait, knowing that any moment that door was going to slide back and you were going to be expected to begin. And it always seemed that you were waiting there for a year, and all kinds of things would go through your mind: “My God! He must really be raking that guy over the coals. What’s he gonna do when he gets to me?” And then you try to go over what your supposed to say, and you can’t remember. And I was so scared waiting there, that I had an "accident," if you catch my meaning. There's not too much I remember from when I was nine years old, but that I remember. Of course, eventually the sliding door opened and I made my confession and it wasn’t that bad at all, but I did have an accident. It didn’t really bother me much because I had a dark suit on and no one could tell by looking at me what had happened; but, I can only imagine how traumatic it must have been for the kid who went after me, trying to figure out who decided to turn confession into a water sport.

What’s important is that I lived to tell the tale, and so will you. Some people are afraid because they haven't been to confession in twenty years or more, and they don’t know how the priest will react to that. And there’s no need to worry about that. You’re not the first person to go to confession and say you haven't been in twenty years. And what if you do go to confession someplace and you do get a mean priest who’s having a bad day? So what? What are you afraid he’s going to do? Punch you out? You finish the confession, get up and leave, say your penance, and hope you get a nicer priest next time. Big deal.

Of course, fear isn't the only reason some people will spare no expense in trying to avoid going to confession; there are psychological and emotional reasons as well, and I want to look at a few of those next week. In the mean time, I would ask you to continue the exercise I recommended last week and today: to get hold of a good examination of conscience, and try using it every evening before you go to bed, maybe just taking parts of it each night as preparation for making a good confession before Christmas or even after Christmas during the Jubilee Year. The goal, of course, is that we can all mean with sincerity what we all prayed together in today's Responsorial from Isaiah: “God indeed is my savior; I am confident and unafraid” (12: 2 RM3).

* In the Byzantine Tradition, the two Sundays immediately preceeding the Nativity point directly to the coming of the Messiah, and the lessons for them are proper to both days: the Sunday of the Forefathers, celebrated today, sometimes called the Sunday of the Patriarchs, and the Sunday of the Ancestors of our Lord, also called the Sunday of the Genealogy, since on that Sunday the genealogy of Our Lord from St. Matthew is read.

The Gospel lessons for these two Sundays point directly to the fact the Jesus is the Messiah for which the Jews had been waiting for two thousand years. Today’s Gospel, the familiar one of the Wedding Banquet, is an allegory for salvation history, explaining how salvation is made possible for everyone by Christ. Next Sunday's Gospel lesson is the entire first chapter of St. Matthew, in which the human genealogy of our Lord is read, bringing home the nature and implications of the Incarnation in a less allegorical and even more graphic way.

|