In this World, There Are Only Heroes and Cowards.

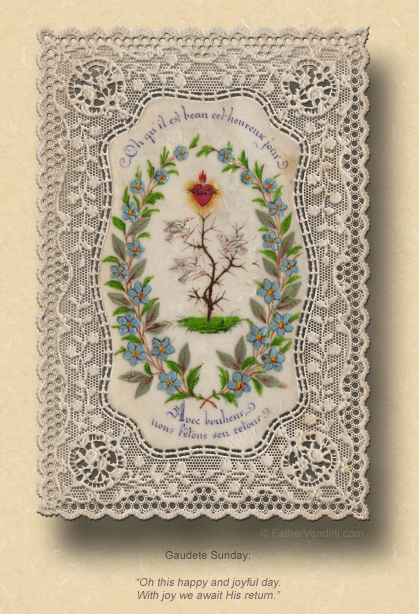

The Third Sunday of Advent, known as Gaudete Sunday.

Lessons from the primary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 25: 1-6, 10.

• Psalm 146: 6-10.

• James 5: 7-10.

• Matthew 11: 2-11.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Philippians 4: 4-7.

• Psalm 79: 2-3, 6.

• John 1: 19-28.

In the United States:

The Sunday of the Forefathers; the Feast of Our Venerable Father Daniel the Sylite; and, the Feast of Our Venerable Father Spiridon the Wonder-Worker, Bishop of Tremithus.*

Lessons from the proper for the Forefathers, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Colossians 3: 4-11.

• Luke 14: 16-24.

|

Outside the United States:

The Sunday of the Forefathers; and, the Feast of Our Venerable Father Daniel the Sylite.**

Lessons from the proper for the Forefathers, as above.

|

FatherVenditti.com

|

1:22 PM 12/11/2016 — Gaudéte in Dómino semper: íterum dico, gaudéte. Dóminus enim prope est. “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I say, rejoice. Indeed, the Lord is near” (RM3). Of course, it's the Entrance Antiphon from which the Third Sunday of Advent takes its traditional name of “Gaudete Sunday,” and it's from Saint Paul. The Introit for the traditional Latin Mass is the same, but actually continues one verse further, and may be more meaningful for some of us: 1:22 PM 12/11/2016 — Gaudéte in Dómino semper: íterum dico, gaudéte. Dóminus enim prope est. “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I say, rejoice. Indeed, the Lord is near” (RM3). Of course, it's the Entrance Antiphon from which the Third Sunday of Advent takes its traditional name of “Gaudete Sunday,” and it's from Saint Paul. The Introit for the traditional Latin Mass is the same, but actually continues one verse further, and may be more meaningful for some of us:

Rejoice in the Lord always: again I say, rejoice. Let your moderation be known to all men: for the Lord is near. Have no anxiety, but in everything, by prayer let your petitions be made known to God (Phil. 4: 4-6 RM 1962)

…from Saint Paul’s letter to the Philippians. And all the lessons presented to us on this day carry with them this sense of joyful expectation. Of course, in both Philippians and the preaching of the Baptist, this joy and expectation is directly linked, as you can plainly see, to the idea that the coming of Christ will mean only one thing: repentance and the forgiveness of sins.

Our first lesson from the Prophet Isaiah is full of this spirit of expectation. His message is simple yet profound: that in the midst of whatever troubles us, we must take courage that the promises of God to His people will be fulfilled:

Stiffen, then, the sinews of drooping hand and flagging knee; give word to the faint-hearted, Take courage, and have no fear; see where your Lord is bringing redress for your wrongs, God himself, coming to deliver you! (35: 3-4 Knox).

And for those who don’t often feel that way, weighed down with personal problems and worries, Holy Mother Church gives us the Apostle James in our second lesson, who advises us to…

Wait, then, brethren, in patience for the Lord’s coming. See how the farmer looks forward to the coveted returns of his land, yet waits patiently for the early and the late rains to fall before they can be brought in. You too must wait patiently, and take courage; the Lord’s coming is close at hand (James 5: 7-8 Knox).

His analogy about the farmer having to wait for the rains before his crops can mature may not seem all that relevant, since most of us aren’t farmers, but we’re smart enough to figure it out. And the use of the word “courage” in both lessons is interesting, because that’s exactly the virtue that our Lord lights on in our Gospel lesson in an indirect way. Many of John the Baptist’s devoted followers drifted to our Lord after John was arrested—primarily because John told them to—but still didn’t quite understand that John was just the envoy.  Distressed at his apparent failure, they turn to our Lord for an explanation, and our Lord minces no words: “What did you go out to the desert to see? A reed swayed by the wind? (Matt. 11: 7 RM3). Distressed at his apparent failure, they turn to our Lord for an explanation, and our Lord minces no words: “What did you go out to the desert to see? A reed swayed by the wind? (Matt. 11: 7 RM3).

Spiritually, there are two kinds of people in this world: heroes and cowards. The coward, overwhelmed with his problems, discouraged by his sins, wallows in self pity and self-recriminations. He stays away from confession because he often thinks he’s unworthy even of God’s mercy. He’s a slave to his passions, but even more so is he a slave to his own lack of self-esteem. The temptations of the world are too much for him, he thinks. He’s convinced himself that the resisting of temptation and the practice of virtue is beyond his ability, so he just wrings his hands in despair. He’s not entirely wrong: overcoming temptation and growing in virtue are beyond everyone’s ability, which is why none of us can do either without God’s Grace, but he’s too infected with the sin of pride to see that.

The hero, on the other hand, is not afraid to gaze into the mirror of his conscience and look himself in the eye. He sees the same sinfulness, he sees the same lack of virtue, because we’re all the same in that regard, but he’s not afraid of what he might see because he’s not infected with pride. He’s not at all put down by the fact he’s not capable of doing it on his own, because he knows he’s not on his own. He’s cataloged every sin he can remember, and marches into the confessional with his head high, and speaks his sins to Christ without whimpering about them, without the tinge of self-pity that marks so many confessions one hears in the course of a week. He’s not presumptuous of God’s mercy, quite the contrary: he’s simply had the courage to see himself as he really is, and knows he can’t change without help—without Grace—and he’s not too proud to ask for it. He may be a sinner, and he may struggle with temptation every waking moment of every day, but he will never be a “reed swayed by the wind.”

Gaudéte in Dómino semper! “Rejoice in the Lord always: again I say, rejoice … Have no anxiety, but in everything, by prayer let your petitions be made known to God.”

* In the Byzantine Tradition, the two Sundays immediately preceeding the Nativity point directly to the coming of the Messiah, and the lessons for them are proper to both days: the Sunday of the Forefathers, celebrated today, sometimes called the Sunday of the Patriarchs, and the Sunday of the Ancestors of our Lord, also called the Sunday of the Genealogy, since on that Sunday the genealogy of Our Lord from St. Matthew is read. The Gospel lessons for these two Sundays point directly to the fact the Jesus is the Messiah for which the Jews had been waiting for two thousand years. Today’s Gospel, the familiar one of the Wedding Banquet, is an allegory for salvation history, explaining how salvation is made possible for everyone by Christ. Next Sunday's Gospel lesson is the entire first chapter of St. Matthew, in which the human genealogy of our Lord is read, bringing home the nature and implications of the Incarnation in a less allegorical and even more graphic way.

Daniel the Stylite (the "tower-dweller") was born in 409 in the upper Euphrates valley, entered the monastic life in his early life, and visited Simeon the Stylite who encouraged him to be more completely detached from the world. In 451 he retired to an abandoned pagan temple near Constantinople, and lived in seclusion, being ordained to the priesthood by Patriarch Gennadius (458-471). He died on this day in 493.

Spiridon was a farmer and the father of many children. After his wife's death, he was consecrated a bishop, and attended the First Council of Nicea in 325. He died in 348, and is the patron saint of the island of Corfu, where his remains are entombed.

** The Ruthenian Church in the United States, along with the Latin Church in this country, observes the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe tomorrow, so that tomorrow's ordinary observance of Saint Spiridon is transfered to today.

|