4:41 PM 11/9/2012 — Once upon a time, a group of people had an idea for a country. They were far from a monolithic group of people. Each one had his own reasons for wanting to design and live in a new country of their own making. Some of them were merchants who found that the country to which they belonged was taxing them so highly that they could not make ends meet. Some of them were philosophical idealists who were uncomfortable with the abstract notion of hereditary rule. Some of them were passionate believers whose religion of choice or birth had been declared seditious and illegal in the country they called home. Some of them were adventuring individualists who simply didn't like the idea of living life while beholden to anyone or anything. The one thing—in point of fact, the only thing—they shared with one another was the common sense realization that none of them could find what he or she was looking for on his own, that they needed to combine their efforts to create a society which, while seeking to meet the individual desires of each of them, would sufficiently pool their meager resources to enable them to achieve them.

The challenges were monumental. First, each one had to be willing to give up everything he had worked for all his life and leave it behind; each one knew that, once he started down the path of forging a completely new life, there would be no possibility of going back. Next, they had to butt heads with the Divine Right of Kings, which would most certainly brand each one as a traitor.  Then, they had to find a place to live, someplace which was not now under any king, some far away place which was, for all intensive purposes, ungoverned. Finally, not being naive, each one knew that, once created in mind, what they made would have to be defended in blood, as the Divine Right of Kings doesn't easily step aside simply when told it is no longer desired—one does not tell God his services are no longer required.

Then, they had to find a place to live, someplace which was not now under any king, some far away place which was, for all intensive purposes, ungoverned. Finally, not being naive, each one knew that, once created in mind, what they made would have to be defended in blood, as the Divine Right of Kings doesn't easily step aside simply when told it is no longer desired—one does not tell God his services are no longer required.

For all of our vaulted platitudes about that thing called freedom, it is both sobering and arresting—yet necessary—to remember that the American experiment began as a protest against a confiscatory tax. There is little point to debating whether the Stamp Act was unjust, only to recognizing that many who had been made the subject of it without their consultation thought it so. Nor would it be be correct to assume that all were agreed as to what could—or even should—be done about it. Human history was not unaccustomed to the concept of revolution; but, such uprisings had always been power struggles: one side desiring what the other side had. Never before had a revolution been waged because the very concept—of one person or group of people having rights over the means of production possessed by another person or group—was being challenged on a philosophical level. The arguments against such a concept alarmed many, if not most of those involved in the debate. What was being challenged was not a law that had been judged by many as unfair or too harsh, but the very concept of law itself based on anything but the consent of the governed. Say what you want about the so-called republics of ancient Greece and Rome; in reality, this idea had never been heard before; and, for some, it was sheer madness. If carried though, so many voiced, civilization itself would collapse into utter chaos.

School children today are never taught the most important words spoken or written by any Founding Father of the American Republic, because they are not found in any of the so-called “founding documents”; not in the Declaration of Independence, not in the Constitution, not in the Bill of Rights. They were spoken by a forgotten man before a handful of people, a man who did not favor revolution, a man who believed himself to be a loyal subject of his king. His purpose was nothing more than to play “Devil's Advocate,” to toss a point of cogent debate before those who feared that challenging the established order was an affront to God. On December 20th, 1765, James Otis, a member of the Council of Boston, rose to briefly address the subject of the Stamp Act:

It is a strange kind of law which we hear advanced nowadays, that because one unpopular Act can't be carried into execution, that therefore there shall be an end of all law. We are not the first people who have risen to prevent the execution of a law; the very people of England themselves rose in opposition to the famous Jew-bill, and got that immediately repealed. And lawyers know that there are limits, beyond which, if parliaments go, their acts bind not.

The king is always presumed to be present in his courts, holding out the law to his subjects; and when he shuts his courts, he unkings himself in the most essential point.

It was the first time in human history that anyone suggested that the law ruled even the one who had created it, and it was heresy.

Looking back 247 years later, it would be too braggadocios to suggest, as some do, that all the motives for the American Revolution were of equal merit. Protesting “taxation without representation,” for example, doesn't compare with Lord Baltimore leaving behind his ancestral home and his considerable fortune to create a place where Catholics, whose faith had been proclaimed illegal  in their own country, could live and worship as they chose, creating the first place on the planet where freedom of religion—even non-Catholic religion—was guaranteed, naming it simply “Mary Land” after the Blessed Virgin; but, regardless of the varying motives, what all the “scientists” involved in the American experiment had in common—what all of them needed and were willing to fight and die for—was something that, today, is regarded as reckless madness even in the country they created: the pursuit of the Ungoverned Life.

in their own country, could live and worship as they chose, creating the first place on the planet where freedom of religion—even non-Catholic religion—was guaranteed, naming it simply “Mary Land” after the Blessed Virgin; but, regardless of the varying motives, what all the “scientists” involved in the American experiment had in common—what all of them needed and were willing to fight and die for—was something that, today, is regarded as reckless madness even in the country they created: the pursuit of the Ungoverned Life.

We conservatives like to throw about words that we think reflect the thoughts of our Founding Fathers, yet they are words and concepts those Fathers would not have recognized. “Big government” verses “small government” is just one example. But when the founding of a new country was being debated seriously, it was the very notion of “government” itself that was on the chopping block:

Society in every state is a blessing, but government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil; in its worst state, an intolerable one; for when we suffer, or are exposed to the same miseries by a government, which we might expect in a country without government, our calamity is heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer. Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence; the palaces of kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of paradise.

Read those two run-on sentences to anyone you meet on the street and ask them to identify them. Chances are you'll hear everything from a rant by Rush Limbaugh to Timothy McVeigh's “farewell” speech before being strapped to the gurney. In February, 1776, no one—least of all himself—regarded George Washington, a gentleman farmer from Virginia, a “right wing kook”; but, reading those words from Thomas Paine's pamphlet, Common Sense, before groups of men would prove to be his most successful tool in recruiting for the Continental Army. They didn't sign up because of the Stamp Act, nor because someone had come around seeking to burn their Bibles or string them up by their Rosary beads; they signed up because they were gentleman farmers, too, who believed that their homes and their land belonged to them, and that no one had the right to come around and take money from them because he said he was “from the government.” In this respect, the actual fighting of the American Revolution was a war against something for which a term did not exist at the time, but which we call “the common good.”

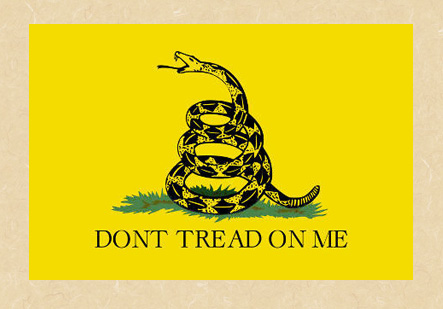

Like it or not—and most of the people who voted in the last election clearly won't—the Republic of the United States was founded upon the principle that individual liberty is more important than the common good. And like it or not—and perhaps everyone won't—there is only one right that the American person does not have: the right to redefine the country and decide, even though a democratic process, that its founding principle should now be changed. Majority rule can be just as cruel a tyrant as can a king. The American people do not have the right to decide that health care is so expensive that freedom must be mitigated to ensure that all have it. They do not have the right to decide that those who have made more money than others must be required to give some of it to those less fortunate. That there may be a Christian duty to do these things is between each person and his God, but the government has no authority to enforce the Gospel. Why not? Because God Himself says so, and He will make it all balance out in the end. That's why there's a First Amendment. If the concept of a balance in the Final Judgement does not satisfy, it is only because so many have ceased to believe in God or His Judgement. Should the people so forget themselves as to elect a government that has forgotten it...well, that's why there's a Second Amendment, so that those who still remember can correct the error.

Every general election, regardless of the issues or the candidates, their strengths or weaknesses, their visions or their policies, is ultimately a referendum on the concept of what it means to be an American. For myself, having taken the time to read the historical record, beginning with James Otis' brief intervention in Boston about the Stamp Act, to the 27th Amendment of the Constitution, I can only conclude that an American is someone who longs for the Ungoverned Life; or, to put it more boldly, anyone who does not long for the Ungoverned Life is not a true American.