A Judgment Rooted in the Truth is Without Malice.

The First Sunday of Advent.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Jeremiah 33: 14-16.

• Psalm 25: 4-5, 8-10, 14.

• I Thessalonians 3: 12—4: 2.

• Luke 21: 25-28, 34-36.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Romans 13: 11-14.

• Psalm 24: 3-4.

• Luke 21: 25-33.

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:25 AM 11/28/2021 — Those of you who hear or read these homilies regularly know that whenever I quote the Holy Scriptures, nine times out of ten I quote from the Knox Bible, released in pieces at the beginning of the last century, but finally published in a single volume for the first time in 1954. It was a labor of love done by one man, Msgr. Ronald A. Knox, an English priest and convert to Catholicism who was—and probably remains—the greatest classical language scholar who ever lived. Every year, on the First Sunday of Advent, I mention him, and always say that, one day, I’ll tell you the fascinating story of his life and work, but then I never do. Nor am I going to do so today, except in one respect. 9:25 AM 11/28/2021 — Those of you who hear or read these homilies regularly know that whenever I quote the Holy Scriptures, nine times out of ten I quote from the Knox Bible, released in pieces at the beginning of the last century, but finally published in a single volume for the first time in 1954. It was a labor of love done by one man, Msgr. Ronald A. Knox, an English priest and convert to Catholicism who was—and probably remains—the greatest classical language scholar who ever lived. Every year, on the First Sunday of Advent, I mention him, and always say that, one day, I’ll tell you the fascinating story of his life and work, but then I never do. Nor am I going to do so today, except in one respect.

Among his many accomplishments—and, believe me, there are many—he was known as a very gifted preacher, and one of the first sermons of his I read was an Advent sermon he preached in 1947.

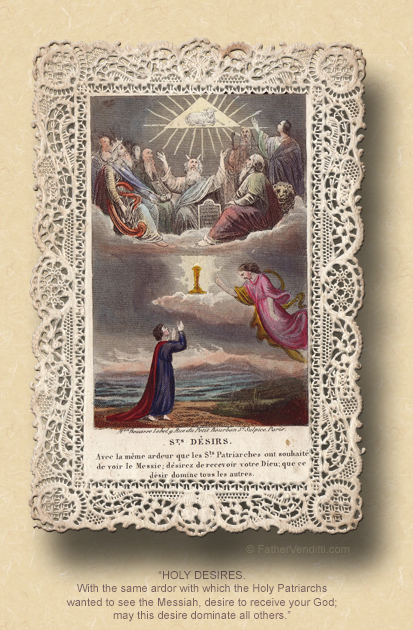

Everybody knows [says Msgr. Knox] what it is to plod on for miles, it seems, eagerly straining your eyes towards the lights that, somehow, mean home. How difficult it is, when you are doing that, to judge distances! In pitch darkness, it might be a couple of miles to your destination, it might be a few hundred yards. So it was, I think, with the Hebrew prophets, as they looked forward to the redemption of their people. They could not have told you, within a hundred years, within five hundred years, when it was the deliverance would come. They only knew that, some time, the stock of David would burgeon anew; some time, a key would be found to fit the door of their prison house; some time, the light that only showed, now, like a will-o'-the-wisp on the horizon would broaden out, at last, into the perfect day.*

I don't think anyone but Father Knox could have expressed so clearly, in just a few sentences, what Advent is really all about. We all think we know what Advent is: a preparation for Christmas; but, as Msgr. Knox so beautifully tells us, the Church's intention in Advent is to encourage in us a reproduction of the spirit of the Old Testament prophets calling forth repentance upon the people of Israel as they awaited the coming of the Savior. The readings for the Advent season rely heavily on the prophets, particularly the prophet Jeremiah; even the Gospel lessons chosen frequently present to us those occasions—and there were many—wherein our Lord quotes from the prophets; and, if we take them as a whole, we realize that what most of us think Advent is about isn't really what it's about. Recall the Collect that the priest prayed at the beginning of Mass today: “Grant to your faithful, we pray, almighty God, the resolve to run forth to meet your Christ with righteous deeds at his coming, so that, gathered at his right hand, they may be worthy to possess the heavenly Kingdom.” There's no mention of Christmas there; the Advent we await is not the coming of the Baby Jesus in the Manger; the Advent we await is the coming of Christ the King and Judge of the world. In other words, it's the not the first coming of Christ for which the season is preparing us; it's His second. In fact, up until the sixth century, when Pope Saint Gregory introduced this season, which had been observed locally in various places, to the whole Church, it was typically called the “Christmas Lent,” even though Christmas was not its focus.  From the beginning, it was meant clearly as a penitential season: no Gloria is sung at the Sunday Mass, and the priest wears the color of Lent. The focus of it is helping us to prepare for death and our final judgment. From the beginning, it was meant clearly as a penitential season: no Gloria is sung at the Sunday Mass, and the priest wears the color of Lent. The focus of it is helping us to prepare for death and our final judgment.

I shouldn’t tell you this story because it’s both petulant and personal, but I think it makes a point. The era in which I was ordained to the Priesthood was a very difficult and turbulent period in the Catholic Church. People’s heads were still spinning following the aftermath of the Second Vatican Council, as it seemed that even the very basics of the faith were up for grabs. Pope Saint John Paul II had just been elected, but hadn’t had a chance yet to attempt to put things back in order; so there was a great deal of confusion as to what direction the Church would take. Some might argue that we’ve regressed somewhat to that point again;—I don’t want to get into that—but, to illustrate how difficult a time it was, nearly half of the men ordained at the time I was ended up leaving the priesthood at some point, for a variety of reasons. My second assignment as a parochial vicar was in a very large city parish, one of those old fashioned Irish parishes that don’t exist anymore, with four or five priests living in the rectory and six or seven Masses on a weekend. I had arrived around this time of year, the beginning of Advent, and my first sermon in the parish was on this very topic of our final judgment. And the pastor of the parish, God rest his soul, who was a good priest in many ways but who had clearly been out in the trenches a little too long, flew into a rage. “You can’t preach anything like that here! We want to draw people in, not drive them away! We don’t talk about sin in this church.” And I asked him, “Okay, for the sake of argument, let’s say you’re right, and our job is make our parish the ‘home of the range,’ where never is heard a discouraging word and the skies are not cloudy all day, and we succeed in packing the place up to the rafters with people by only preaching what people want to hear. Then what? Once we’ve got them in there, what do we do with them? At what point do we begin to preach to them the truth? If we really care about people, shouldn’t we want them to saved?” And he looked at me as if I had been speaking Vietnamese.

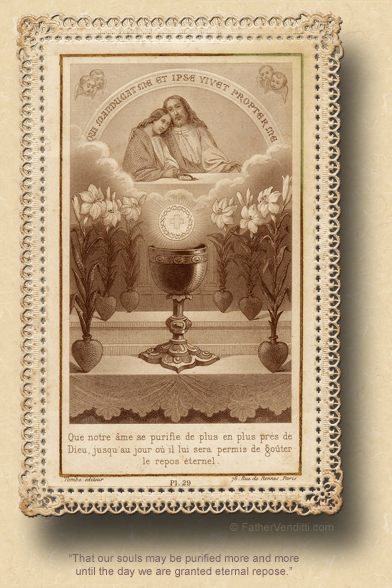

Those days are pretty much over, thank God, and yet, there remains that delicate balancing act the Church must walk between offering her people a message of hope in the midst of their sufferings, and reminding them that the responsibility of working out their salvation rests squarely on their own shoulders. Christ, through His Church, has provided us with tools to help, primarily confession and Communion, but we have to motivate ourselves to use them. That’s why I think Msgr. Knox’s advent reflection is so valuable in understanding what Advent should mean for us. The longing of the Old Testament prophets for the coming of the Messiah is an analogy of what should be our own longing for the coming of Christ at the end of all things, and the particular judgment that goes with it.  Christ will come again to judge us, and His judgment will be exacting; but, his judgment is without malice, rooted firmly in the truth. That’s the beauty of Catholic dogma about Purgatory: we don’t have to be perfect to be saved; we only have had to have tried our best; and, if we have tried out best, then we know we will go to heaven, even if our arrival there is delayed for a time so that what remains of selfishness in us can be burned away. Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman, who, like Knox, was a convert to the faith, insisted that the souls in Purgatory are joyful because they know for certain that their salvation is assured. Christ will come again to judge us, and His judgment will be exacting; but, his judgment is without malice, rooted firmly in the truth. That’s the beauty of Catholic dogma about Purgatory: we don’t have to be perfect to be saved; we only have had to have tried our best; and, if we have tried out best, then we know we will go to heaven, even if our arrival there is delayed for a time so that what remains of selfishness in us can be burned away. Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman, who, like Knox, was a convert to the faith, insisted that the souls in Purgatory are joyful because they know for certain that their salvation is assured.

The irony of this season of Advent is that, while it precedes Christmas and does serve—at least toward the end—as a preparation for celebrating our Blessed Lord’s birth, most of it is asking us to contemplate not birth but death, and the need to be always prepared for it. In the very first Gospel lesson given to us to hear on the first day of the Year of Grace, our Lord admonishes us to consider our final judgment. The lesson He’s giving to us is simplicity itself: the Christian needs to live every minute of his life conscious of the fact that life is short, that it can be required of us by God at any time, and that we should always keep our souls prepared by suppressing our vices, seeking the Lord’s constant grace in confession when we sin, and by steeling ourselves against temptation by staying ever close to our Blessed Lord through frequent and worthy Holy Communion. Given the prospect of final judgment, that’s just common sense; but, you know what they say about common sense: that it isn’t always so common, especially when we are so easily distracted by the concerns of daily life.

Only look well to yourselves; do not let your hearts grow dull with revelry and drunkenness and the affairs of this life, so that that day overtakes you unawares; it will come like the springing of a trap on all those who dwell upon the face of the earth (Luke 21: 34-5 Knox).

So, let our resolution today, as we begin a new Church year and a new season of Advent, be that we will watch. That we will turn our thoughts often to God. That we will examine our consciences honestly and completely, and confess our sins truthfully and frequently, and that we will march toward our final judgment not in fear, but in confidence, convinced that the absolute truth about ourselves, accepted in humility, will become our sure portal into everlasting life.

* R. A. Knox, Sermon on Advent, 21 December 1947.

|