Jesus Is Not a Blank Slate.

The Thirty-Third Wednesday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from cycle II of the feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

Revelation 4: 1-11.

Psalm 150: 1-6.

Luke 19: 11-28.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com.

|

1:48 PM 11/19/2014 — Is this the same parable that the Holy Evangelist Mark reported to us in last Sunday's Gospel lesson? The skeleton of both stories is essentially the same: a man going away on a journey entrusted different amounts of his business with different employees, and most of them make investments according to their ability—all but one, in fact, who is roundly punished for not even trying. The punchline of both accounts is certainly the same: “…to everyone who has, more will be given, but from the one who has not, even what he has will be taken away” (Luke 19: 26 NABRE). 1:48 PM 11/19/2014 — Is this the same parable that the Holy Evangelist Mark reported to us in last Sunday's Gospel lesson? The skeleton of both stories is essentially the same: a man going away on a journey entrusted different amounts of his business with different employees, and most of them make investments according to their ability—all but one, in fact, who is roundly punished for not even trying. The punchline of both accounts is certainly the same: “…to everyone who has, more will be given, but from the one who has not, even what he has will be taken away” (Luke 19: 26 NABRE).

But there are differences between the accounts: for one thing, in the parable as told to us by St. Mark last Sunday, the two of the three servants who got a return on the investments of their master's money all got the same reward; and, if you were here you will remember that we drew a lesson from that. In the account told by Luke today, the nine of the ten who make a profit all get proportionate rewards based on the profits each made. What's even more interesting is the prolog to the parable told by our Lord today, which contains a lot more information than that which he told in Mark's Gospel last Sunday: as St. Mark tells it, Jesus simply says that a man went on a journey, but he doesn't tell us why or where he's going;—it's just not important to the point that Mark wants to make in recounting this parable—but, in today's account, St. Luke reports our Lord actually providing these details and, if we didn't know the history of Palestine and the Jewish people, we would just view these details as extraneous.

The Holy Land, remember, was occupied territory, and every little potentate who ruled anything within the empire had to be approved; so, whenever there was a change in administration somewhere, the new prince or king or whomever was inheriting the territory had to travel to Rome to receive formal investiture by the Emperor and the Senate. In the account we read today from St. Luke, our Lord's parable is very much like an episode of Dragnet, in which the names are changed—or, in this case, left out—to protect the innocent, because our Lord is actually referring to an historical incident. After the death of Herod the Great in 4 BC, his son, Archelaus, went to Rome to be confirmed as his father's successor, but the Jews sent a delegation ahead of him to oppose his succession. Caesar Augustus took the opportunity to use this dispute to make a land grab, and split up the kingdom, giving Judea and Samaria to Archelaus under the title of tetrarch, not king, with the rest of the kingdom of Israel becoming a direct Roman protectorate. A couple of years later, Augustus would depose Archelaus altogether and make the whole of Palestine a Roman province under the procurator Pilate. So, the Jews, who had been willing subjects of the Emperor in the beginning, came to despise their Emperor in the end, causing a lot of unrest; and this is the political situation into which our Savior was born.

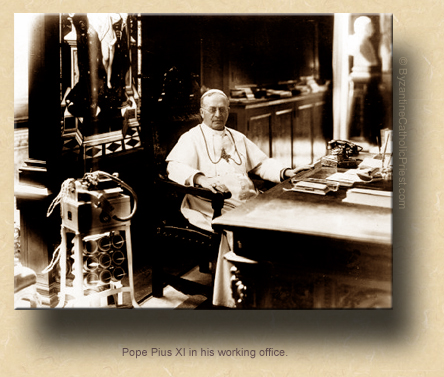

And, seen in this light, the reading of this Gospel lesson today is the perfect lead-up to the Feast of Christ the King which we are to celebrate this coming Sunday. When Pius XI established the feast of Christ the King, he fixed its date for the Sunday directly following the Feast of All Saints, and explained why in his encyclical; when Pope Blessed Paul VI moved the feast to the last Sunday of Ordinary Time he changed the spiritual thrust of the feast completely, and that decision remains controversial to this day; today's Gospel lesson harkens back to the original meaning of Christ the King as envisioned by Pius XI: all authority on earth is derived, directly or indirectly, from the authority of Christ, but that authority is spiritual, not political. The early followers of our Lord clearly saw Him as a political figure with religious overtones; they looked to him to lead some sort of revolution which would overthrow Roman rule and restore independence to Palestine, perhaps even restoring the old Kingdom of Israel. Of course, this was not our Lord's mission.

What I would ask you to take away from this lesson in your meditation today—in addition to what we discussed last Sunday—is simply the fact that we do not have the right to invent Jesus Christ. He is what He is in spite of what any of us think of Him. Judas, more that any other figure in the New Testament, was the extreme example of someone using Jesus as a blank slate on which he projected all of his own personal insecurities and agitations; he was a zealous political activist who interpreted Jesus according to his own point of view, and we know there are people in the Church who do that today. To a certain extent, all of us do it: we use our Blessed Lord as a kind of canvas on which we paint an image that supports what we want Christ and His Church to be. But Jesus is not a blank slate; when his disciples appear perplexed at some of the things He says, it's not because what He's told them is convoluted and opaque; it's because they can't deal with the fact that what He says doesn't fit their template.

The challenge for us is the same as it was for them: to read the words of our Blessed Lord, and allow them to form us rather than look for a way to make them say what we want them to say.

|