In the Name of Jesus Christ, I Offer You a Cup of Coffee.

The Thirty-Third Tuesday of Ordinary Time; or, the Memorial of Saint Albert the Great, Bishop & Doctor of the Church.

Lessons from the secondary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Revelation 3: 1-6, 14-22.

• Psalm 15: 2-5.

• Luke 19: 1-10.

|

When a Mass for the memorial is taken, lessons from the feria as above, or from the proper:

• Sirach 15: 1-6.

• Psalm 119: 9-14.

• Matthew 13: 47-52.

…or, any lessons from the common of Pastors for a Bishop, or the common of Doctors of the Church..

|

The Third Class Feast of Saint Albert the Great, Bishop, Confessor & Doctor of the Church.

Lessons from the common "In médio…" of a Doctor of the Church, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• II Timothy 4: 1-8.

• Psalm 36: 30-31.

• Matthew 5: 13-19.

The First Day of Philip's Fast; and, the Feast of the Holy Martyrs & Confessors Gurias, Samonas & Habib.*

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fourth from the menaion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• I Timothy 5: 11-21.

• Ephesians 6: 10-17.

• Luke 14: 25-35.

• Luke 12: 8-12.

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:26 AM 11/15/2016 — Albert the Great is rightly named. Rarely do we find, even among the saints, a man in whom holiness of life and intellectual power exist side by side. Allow me to read to you the brief biography of him from the Breviarium Romanum of the extraordinary form, which I use for my daily office, in what I hope is a reasonable translation: 9:26 AM 11/15/2016 — Albert the Great is rightly named. Rarely do we find, even among the saints, a man in whom holiness of life and intellectual power exist side by side. Allow me to read to you the brief biography of him from the Breviarium Romanum of the extraordinary form, which I use for my daily office, in what I hope is a reasonable translation:

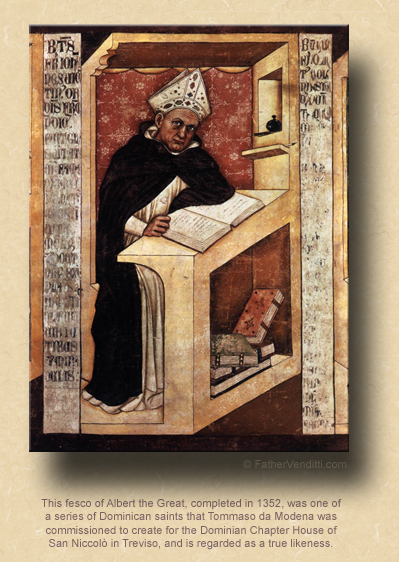

Albert, called the Great, because of his unusual learning, was born at Lauingen on the Danube in Swabia and carefully educated from his boyhood. He left his country to study in Padua. While he was there he applied to enter to the Dominicans. His uncle protested futilely against this step, but Blessed Jordan, master general of the Order of Preachers, encouraged it. When Albert had joined the friars, he was a shining example of religious observance and devotion. He loved the Blessed Virgin Mary above all and burned with zeal for souls. To complete his studies he was sent to Cologne. Then he was made professor at Hildesheim, at Freiburg and Ratisbon and at Strasbourg. In the master's chair at Paris, he earned a high reputation. He had Thomas Aquinas for his beloved disciple and was the first to perceive and predict the loftiness of his intellect. At Anagni, in the presence of the Pope Alexander IV, he refuted William, who had wickedly attacked the mendicant orders. Later he was made bishop of Ratisbon, where, in giving counsel and in settling disputes, he worked such wonders as to deserve the title of peacemaker. He wrote many things about almost all branches of learning, especially the sacred sciences, and composed some famous works about the wonderful Sacrament of the altar. Famous for his virtues and for his miracles, he died in the Lord in the year 1280. By the authority of the pope a cult had long since been granted him in many dioceses and in the Order of Preachers; and, when Pius XI, willingly acceding to the desire of the Sacred Congregation of Rites, extended his feast to the whole Church, he gave him also the title of Doctor of the Church. Pius XII appointed him the heavenly patron with God of all those who study the natural sciences.

Now, turning our attention to today’s Gospel lesson:

I didn’t preach yesterday because Monday is the closest thing I have to a day off, and given that I have to offer the Noon Mass in any case, I try to escape as soon as possible; but, the Gospel lesson, you might recall, was the familiar one of our Lord’s meeting with the blind man, Bartimaeus, sitting along the side of the road to Jericho. We’ve looked at that lesson several times.

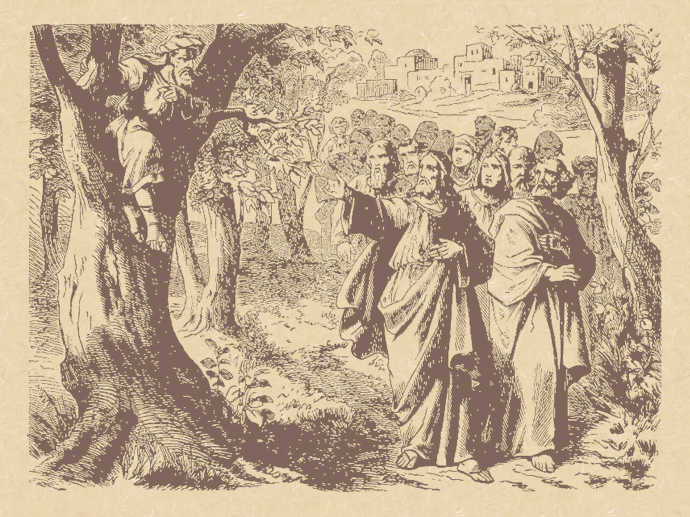

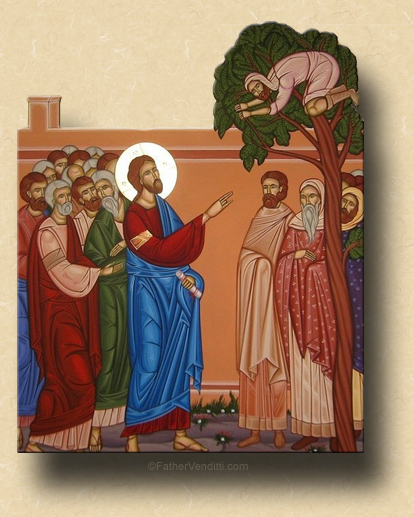

Today’s Gospel lesson we’ve also looked at several times, and just recently since it was offered to us on Sunday just a few weeks ago; so, if you attend Mass here on Sundays you’ll find these reflections familiar. This episode of our Lord’s meeting with Zacchaeus occurs just after His meeting with Bartimaeus while on the way to Jericho.  Today, He's arrived in the city, and the meeting between our Lord and Zacchaeus is painted very vividly by the intuitive Saint Luke. As in His previous encounter, Jesus is simply passing by, and a large number of people have lined the street to catch a glimpse of him. Zacchaeus would like to get a look at Jesus, too; but he’s at the back of the crowd and can’t see anything because, as the Gospel says, he was a relatively short man. So, to get a better look at Jesus, he climbs up a sycamore tree. [One of the Fathers of the Church goes off about the significance of it being a sycamore tree; if you don't mind, I'll skip that bit.] But climbing up a tree not only allows him to see Jesus, it allows Jesus to see him. Why our Lord singles him out will always be a mystery; I like to think that Jesus saw both an opportunity to save a soul as well as make a point. He is, after all, God, and certainly could know, simply by looking at Zacchaeus, exactly what kind of man he was. He also knows that, by inviting Himself to Zacchaeus’ house, He’s going to be raising some eyebrows. You might recall, a few weeks ago on the Feast of Saint Luke, that we discussed how he, being a doctor and the first century equivalent of a psychiatrist, is the only one of the evangelists who ventures to tell us what people were thinking when they observed our Lord; and, here Saint Luke tells us how they all murmured when they saw the two go off together, and whispered to themselves, “He has gone in to lodge … with one who is a sinner” (19: 7 Knox). Today, He's arrived in the city, and the meeting between our Lord and Zacchaeus is painted very vividly by the intuitive Saint Luke. As in His previous encounter, Jesus is simply passing by, and a large number of people have lined the street to catch a glimpse of him. Zacchaeus would like to get a look at Jesus, too; but he’s at the back of the crowd and can’t see anything because, as the Gospel says, he was a relatively short man. So, to get a better look at Jesus, he climbs up a sycamore tree. [One of the Fathers of the Church goes off about the significance of it being a sycamore tree; if you don't mind, I'll skip that bit.] But climbing up a tree not only allows him to see Jesus, it allows Jesus to see him. Why our Lord singles him out will always be a mystery; I like to think that Jesus saw both an opportunity to save a soul as well as make a point. He is, after all, God, and certainly could know, simply by looking at Zacchaeus, exactly what kind of man he was. He also knows that, by inviting Himself to Zacchaeus’ house, He’s going to be raising some eyebrows. You might recall, a few weeks ago on the Feast of Saint Luke, that we discussed how he, being a doctor and the first century equivalent of a psychiatrist, is the only one of the evangelists who ventures to tell us what people were thinking when they observed our Lord; and, here Saint Luke tells us how they all murmured when they saw the two go off together, and whispered to themselves, “He has gone in to lodge … with one who is a sinner” (19: 7 Knox).

Our Lord does not respond to them on this occasion. Later on, when a similar situation presented itself, and our Lord was actually seen dining in the house of a public sinner, He would utter those famous words that would forever be a motto for His ministry:  “It is not those who are in health that have need of the physician, it is those who are sick” (Matt. 9: 12 Knox); but, on this occasion He doesn’t say anything; He just goes with Zacchaeus to his house, and His kindness to Zacchaeus was enough to motivate Zacchaeus to completely change his life. In fact, not only does Zacchaeus change his thieving ways then and there, he also promises our Lord that he’ll pay back everything he’s stolen four times over, and give half of what's left to the poor. Now, that’s bound to make a dent in his standard of living. Zacchaeus made himself rich by stealing people’s tax money; if he pays it back multiplied by four, he’s going end up a poor man. But, apparently, that’s OK with Zacchaeus. The kindness that our Lord showed him by simply acknowledging him as a human being, and going to visit with him in his home regardless of how much it scandalized the self-righteous, meant more to Zacchaeus than anything else he had. “It is not those who are in health that have need of the physician, it is those who are sick” (Matt. 9: 12 Knox); but, on this occasion He doesn’t say anything; He just goes with Zacchaeus to his house, and His kindness to Zacchaeus was enough to motivate Zacchaeus to completely change his life. In fact, not only does Zacchaeus change his thieving ways then and there, he also promises our Lord that he’ll pay back everything he’s stolen four times over, and give half of what's left to the poor. Now, that’s bound to make a dent in his standard of living. Zacchaeus made himself rich by stealing people’s tax money; if he pays it back multiplied by four, he’s going end up a poor man. But, apparently, that’s OK with Zacchaeus. The kindness that our Lord showed him by simply acknowledging him as a human being, and going to visit with him in his home regardless of how much it scandalized the self-righteous, meant more to Zacchaeus than anything else he had.

It’s very easy to hate evil people, especially if we are among their victims. The people in Jericho hated Zacchaeus because he had stolen their money; but, it wasn’t their hatred of him that moved him to give them their money back with interest, it was an act of kindness performed by a stranger. Now, admittedly, that stranger happened to be God, and enjoyed a certain degree of intuition that the good populace of Jericho didn’t have; nevertheless, you don’t have to be God to be kind to people, especially to people whom it may be very popular to hate.

Jesus didn’t do all that much for Zacchaeus comparatively speaking: He didn’t give him back his sight, or make him walk when he was crippled, or bring his dead daughter back to life;—things that He had done for others—all He did for Zacchaeus was have a cup of coffee with him in his house. To us, it doesn’t seem like much;—it may not have seemed like much to our Lord—but, to Zacchaeus, it meant everything. It just goes to show that you never can tell how much good you can do by doing the simplest things.

* Gurias and Samonas, priests of Edessa, were martyred under Emperor Diocetian. Habib, a deacon, was martyred under Emperor Lycinius.

Philip's Fast, the season of penitential preparation for Christmas, so named because it begins on the day after the Feast of the Apostle Philip on the Byzantine Calendar, corresponds to the Roman Rite season of Advent, though it's origins are much later, dating no earlier than the thirteenth century. Lasting for six weeks rather than the four of Advent, what is required during this period varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. The traditional observance would be a strict abstinence from both meat and dairy products on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, with wine and oil allowed on Tuesdays and Thursdays; then, beginning on December 10th in some Churches and on December 20th in others, the strict abstinence becomes daily except on Saturdays and Sundays on which there is traditionally never a fast. The Particular Law of the Ruthenian Metropolia in the United States (Canon 880, § 2) recognizes Phillip's Fast as a penitential season, states the traditional observance, then requires that it be observed voluntarily according to one's individual ability … not unlike the observance in the Latin Church, in which nothing is specifically required.

|