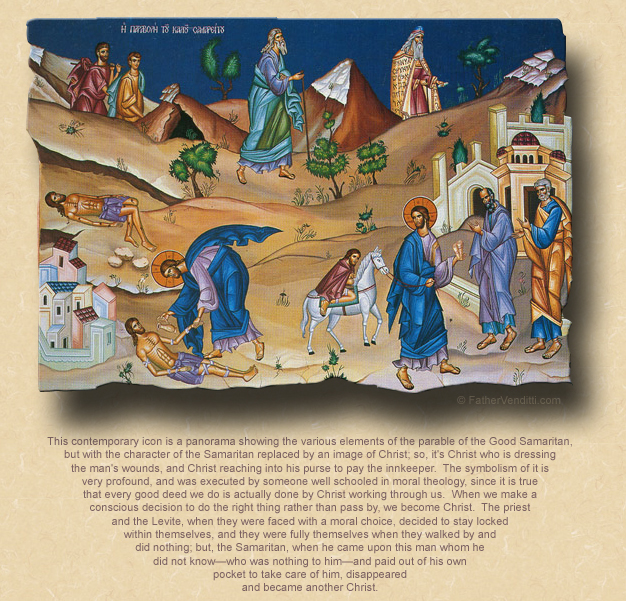

The Good Samaritan: the Occam's Razor of the Bible.Gal. 6:11-18; Luke 10:25-37.* The Twenty-Second Sunday after Pentecost, known as The Eighth Sunday of Luke & the Sunday before Phillip's Fast. The Eighth Sunday after the Holy Cross; also, our Holy Father John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

12:34 PM 11/13/2011 — The parable of the good Samaritan is so familiar to us that we might be tempted to think it has nothing new to teach us. A rabbi, asks our Lord what he must do to be saved. In the translation we have in our Gospel book, St. Luke calls him a lawyer, which, in New Testament times, was what a rabbi was: someone learned in the Law of Moses. There's no reason not to suppose his question is a sincere one; and, like any good rabbi, Jesus answers his question with a question: “What is written in the law?” What does the law of Moses say is required for salvation? It's a very easy question for this man to answer; the Book of Deuteronomy is quite clear and simple: “Love God above all else, and love your neighbor as yourself.” And our Lord is just as simple and straight forward, and says, “Do that, and you will be saved."

Why this very simple and straight forward answer doesn't quite satisfy the rabbi we could speculate about. St. Luke says it's because “he wanted to justify himself.” Exactly what that means I'm not sure. Maybe he was trying to impress our Lord; maybe he was trying to trick our Lord into saying something for which he could later denounce him; we don't know. But, whatever the reason, the simple idea that what the Law of Moses says is exactly what it means doesn't satisfy him. He is colliding with what we could call—for those of you who studied physics—the Occam's Razor of the Bible; and so, he decides to open up Pandora's Box by asking the very delicate and provocative question: “Who is my neighbor?”

Of course, even before we hear the beautiful little story told by our Lord, we already know the answer, and probably so did everybody else who was standing around our Lord that day; and our Lord makes that point very clearly by making the hero of his story a Samaritan: a member of a race of people hated by the Jews. Notice that, after the story is over, when our Lord asks the rabbi which character acted as a real neighbor, the man so hates the Samaritans that he tries to skirt the issue by saying, “The one who treated him with compassion." He can't even bring himself to say the word, "Samaritan."

What I would ask you to reflect upon today, especially this week as we enter into Phillip’s Fast, is the fact that the rabbi wouldn't have gotten himself into this embarrassing situation if he had accepted the simplicity of our Lord's answer in the first place. We, of course, are thankful that he didn't; otherwise our Lord wouldn't have told this beautiful little story; but the original answer given by our Lord should have enough: "What must I do to be saved?"

"What does the law of Moses say?"

"Well, the law of Moses says this?”

"OK, go and do that, then.” But for this man, who thinks himself smart, it's too simple. He's looking for something profound; he's looking for something intricate and elegant; he's looking for something that can be picked apart and studied. And how often we are just like this man!

My guess is that when the rabbi asks Jesus, "Who is my neighbor?" he already knows the answer. But he doesn't like that answer; so he asks our Lord anyway, hoping that our Lord will say something so complicated and convoluted that he will be able to twist it around in his own mind to mean something completely different, something easier for him to live with. Of course, that doesn't happen. Our Lord sticks to his guns, makes his point even more clearly in the story that he tells; and so the man is stuck with an answer he doesn't want, but which is nonetheless true. And it's exactly in this way that we so often imitate this rabbi. How many people are there, do you suppose, having some personal problem with the teaching of the Church—whether it’s about the Church’s teaching on morality, or our liturgical obligations, or fasting on the appointed days, or whatever; it doesn’t matter what—who will shop around and talk to four or five priests until they find one who will tell them what they want to hear? It’s not hard: there are all kinds of priests floating around out there who will tell you whatever you want. Just like the rabbi in the Gospel. He knows exactly who his neighbor is. There's no ambiguity about it. He knows exactly what it means. But he doesn't like what it means; so he asks, "Well, who exactly is my neighbor?" thinking that if he asks the question in a different way, he'll get a different answer, an answer that he can play with. Our Lord sees through his hypocrisy, and hits him right between the eyes by telling him a story that drives home the point even more forcefully, by setting up as an example of brotherly love a man whom the rabbi has been taught from childhood to hate.

Before he ascended into heaven, our Lord entrusted his Church to his apostles and their successors, and charged them to teach what was necessary for salvation in his name. He imparted to them the Holy Spirit, so that when they teach in his name they cannot teach error. There will be times—for some more than for others—when we will not like what they teach. When that happens, we have to make a choice: we can waste our time looking for clever and convoluted ways to get around what they teach; or we can set our eyes on heaven, resolve to make the sacrifices necessary for salvation, confident that, even if we fail from time to time, we can confess our sins and start again as many times as we have to, just so long as we don't try to fool ourselves.

Father Michael Venditti

* Due to the "Lucan Jump," the Gospel read today is that for the 25th Sunday after Pentecost. Cf. the note appended to the Fifteenth Sunday after Pentecost.

|