We Come to Christ for Salvation, not Therapy.

The Memorial of Saint Josaphat, Bishop & Martyr.

Lessons from the secondary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• III John 5-8.

• Psalm 112: 1-6.

• Luke 18: 1-8.

|

…or, from the proper:

• Ephesians 4: 1-7, 11-13.

• Psalm 1: 1-4, 6.

• John 17: 20-26.

…or, any lessons from the common of Martyrs or the common of Pastors.

|

The Third Class Feast of Saint Martin, Pope & Martyr.*

Lessons from the common "Si díligis me…" for One or Several Holy Popes, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Peter 5: 1-4, 10-11.

• Psalm 106: 32, 31.

• Matthew 16: 13-19.

The Twenty-Fifth Saturday after Pentecost; the Feast of Our Venerable Father John the Merciful, Patriarch of Alexandria; the Feast of Our Venerable Father Nilus; and, the Feast of the Holy Martyr Josaphat, Archishop of Polotsk.**

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second from the menaion for both the Martyr & the Patriarch, fourth from the menaion for the Martyr, fifth from the menaion for the Patriarch, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:***

• Galatians 3: 8-12.

• Hebrews 4: 14—5: 6.

• Luke 9: 37-43.

• John 10: 9-16.

• Luke 6: 17-23.

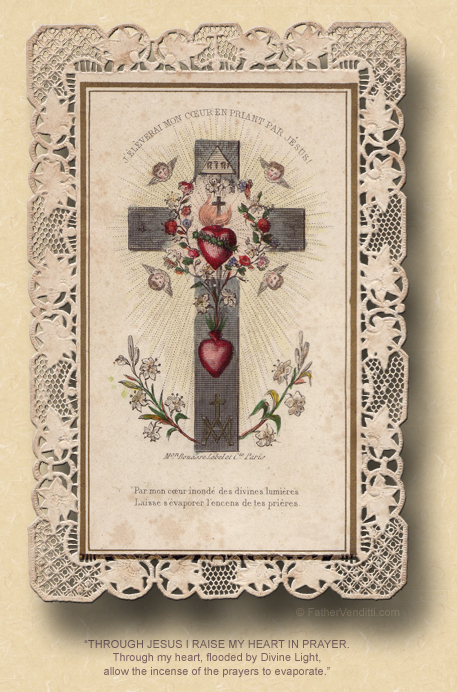

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:39 AM 11/12/2016 — Today’s memorial is one that has significance for me, inasmuch as I served for most of my priesthood in an Eastern Catholic Church. Saint Josaphat was born into the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Poland in 1623, but was received into the Catholic Church and joined the Basilian Order, which was—and is—a monastic community of the Ruthenian Catholic Church in which I served. After the establishment of the Ukrainian Catholic Church he became its first bishop, and spent his life working to bring Orthodox Christians into union with Rome, and these efforts led to his murder. While the official biography of him cautiously avoids accusing the Orthodox of complicity in his death, that’s just political correctness; there’s no doubt that he was murdered by the Orthodox, and everybody knows it, even though the Holy See still refuses to say so. He was canonized in 1867, the first Eastern Catholic to be raised to the dignity of the Altar. Now, to today’s Gospel lesson.

Being as retrospect as I must for obvious reasons, it’s clear that a lot of confessions I’ve heard in the past couple of months have fermented out of the same general collective nexus:—it’s remarkable how people can have the same collective thoughts without even knowing one another—everyone is agonizing over the future of the country—not so much now, but they had been,—the state of the Church, the seeming sterility of their prayers and the emptiness of their profound solitude in the midst of such uncertainty. We don’t reject the consolation that the Virtue of Faith commands; we just don’t feel it. And everyone I admonish agrees that faith can’t be reduced to an emotional response, everyone agrees when I tell them that God is there and hears our prayers even when we don’t feel His presence, everyone agrees when I quote to them Saint John of the Cross of Saint Teresa of Avila about navigating the Dark Night of the Soul; then, they leave the confessional and return to the morose and depression that comes from the constant confrontation of “what is” verses “what should be.”

The Gospel lesson of today’s Mass focuses our attention on the power of trusting and persevering in prayer: Saint Luke, in the reporting of a parable told by our Blessed Lord, begins his account with an editorial prologue:—the only one of the Evangelists that does this—“Jesus told his disciples a parable about the necessity for them to pray always without becoming weary” (18: 1 RM3). Why does he do this?  The parable itself is pretty straight forward; it doesn’t require a secret decoder ring to decipher. The officious judge who cares not a lick for genuine justice grants a just judgment to the poor widow simply because she nags him so incessantly that he gives her what she wants just to get her off his back; the lesson being that, if the judge, who cares nothing for a poor widow, gives her what she wants simply because she’s a pain in the butt, then what about God who loves us beyond measure? The parable itself is pretty straight forward; it doesn’t require a secret decoder ring to decipher. The officious judge who cares not a lick for genuine justice grants a just judgment to the poor widow simply because she nags him so incessantly that he gives her what she wants just to get her off his back; the lesson being that, if the judge, who cares nothing for a poor widow, gives her what she wants simply because she’s a pain in the butt, then what about God who loves us beyond measure?

Saint Augustine was one of the first to recognize the “Catch-22” in between the lines of this passage: we pray to God in desperation because our faith is in turmoil, but prayer is fueled by the measure of the faith from which it springs; so, if our faith has been weakened by temptations to despair, then the prayer arising from it is weak and has no effect. The source of all good prayer is faith; but, as Augustine said in the fourth century, “If one’s faith weakens, prayer withers … Faith is the fountain of prayer … A river cannot flow if its source is dried up.”1 In other words, we run to God with desperate prayers, but it’s that very desperation that renders our prayers weak. “…[I]f you have faith the size of a mustard seed,” said our Lord, “you will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move. Nothing will be impossible for you” (Matt. 17: 20 NABRE); the irony being that, if we did have enough faith to move mountains, we probably wouldn’t pray all that much, since most of us only pray when we need something.

So, if the efficaciousness of our prayer is determined by the strength of our faith—which is clearly what our Lord is saying—but we are driven mostly to prayer when our faith is faltering, then what do we do? How do we escape this “Catch-22”?

We are suffering—many of us—because we have been brainwashed by this therapeutic mentality in which our society has maneuvered us, thinking that the whole point of prayer—of religion itself—is to bring us peace of mind and heal our emotions, because we have allowed Dr. Phil to become our pope.  Faith has nothing to do with emotion, and prayer has nothing to do with feeling better about ourselves. We believe because what we believe is true, and we pray because the God who made us deserves our prayer and worship. How it makes us feel is irrelevant. Faith has nothing to do with emotion, and prayer has nothing to do with feeling better about ourselves. We believe because what we believe is true, and we pray because the God who made us deserves our prayer and worship. How it makes us feel is irrelevant.

And if you doubt that you’ve been poisoned by this therapeutic mentality, look at how most Catholics in this country view the sacraments of of the Church: not as sources of Grace but of rites of passage. A prominent Catholic politician is told by her bishop that she may no longer receive Holy Communion in a Catholic church because of her stand on abortion, so what does she do? She and her family take her grandchildren to an Episcopalian church to be baptized because, for her, baptism isn’t the cleansing of original sin and the restoration of Sanctifying Grace, it’s just a social event for the benefit of family and friends, and has nothing to do with eternal salvation. Marriage isn’t a covenant between two people and their God authorizing them to cooperate in the miracle of creation; it’s just a celebration of love. Confession isn’t the acknowledgment of and absolution from our sins; it’s just a form of free counseling. A funeral isn’t an appeal to God to speed the soul on its journey and keep it safe until the final resurrection; it’s just a form of theatrical grief counseling for the bereaved. And the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass isn’t the Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of our Lord, God and Savior, Jesus Christ, offered for our sins on the altar of the Cross; it’s just a gathering of togetherness around the table of fellowship. When even the sacraments of the Church become therapeutic rather than salvific, that’s when we know our brainwashing in the vapid spirit of this age is complete, and that’s when we begin to think that prayer has something to do with how we feel.

Let’s go back to the officious judge and the poor widow. The judge is in the wrong job: he doesn’t care about justice, and the widow’s case doesn’t interest him because she’s got nothing that he needs or wants. We are just like him whenever we say, “I pray and pray and pray and don’t get anything out of it.” Who says we’re supposed to get something out of it? Our Lord never told us that. None of the saints ever told us that. The only thing we’re supposed to get out of it—if that’s how you want to put it—is that, when this life is over, we go to heaven. Forgive me for saying this for the “umpteenth” time:—you might as well put it on my tombstone on the hill up here—our one reason for being on this earth is to work out our salvation; everything else is just window dressing.

* Not to be confused with yesterday's saint, Pope Saint Martin I suffered much persecution in his defence of the Catholic Faith against the Monothelite emperors of Constantinople. The Monothelites believed that Christ, while he had two natures (human and divine), had only one will, whereas the Catholic Church has always taught that Christ has both a human and a divine will. Pope Saint Martin was exiled and died in the year 655.

** John was elected Melkite Patriarch of Alexandria in 609. He is called "the Merciful" because of his great and generous love for the poor. He died in 619.

Nilus was governer of Constantinople at the time of Emperor Theodosius the Great. In 309 he gave up his high position and his family to retire on Mount Sinai where he become a simple monk. He died in the year 430, and left behind many writings on the spiritual life.

*** Inasmuch as the Apostolic lesson for both the Martyr and the Patriarch is the same, it need only be sung once.

|