For the Christian, "being yourself" isn't all it's cracked up to be.Eph. 2:14-22;

Luke 10:25-57.* The Twenty-Fourth Sunday after Pentecost. The Eighth Sunday after the Holy Cross. The Holy Martyrs Menas, Victor & Vincent. The Holy Martyr Sephanis. Our Venerable Father & Confessor Theodore the Studite. The Passing of the Blessed Martyr & Bishop Vincent Eugene Bossilkov in Bulgaria.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

1:30 PM 11/11/2012 — Last year, when this parable of the Good Samaritan came up, I reminded you that it is one of two Gospel lessons that begin in the same way: with someone approaching our Lord and asking what must be done to be saved. In each case our Lord gives the same simple answer, but in this case the Rabbi who asks the question wasn't satisfied with the simple answer, and wanted something more. St. Luke says it was because he wanted to “justify himself,” whatever that means. This prompts our Lord to tell the parable, which features as its hero a man from a race of people whom the Rabbi has been trained from childhood to hate. What I asked you to take away from that was that the simplicity of our Lord's original answer to him, to keep the Commandments, should have been enough, but it wasn't because the Rabbi was too clever for his own good. And I suggested that we often have the tendency to imitate the bad example of this Rabbi by trying to make life's moral questions more convoluted than they really are; that sometimes the simplest answer is the correct one. That's why I referred to the parable of the Good Samaritan as the Occam's Razor of the Bible. People who, for example, shop around for a priest who will tell them what they want to hear do not do themselves any favors, since finding someone willing to bend the rules for you does not force our Lord to bend the rules for you on the day of your judgment.

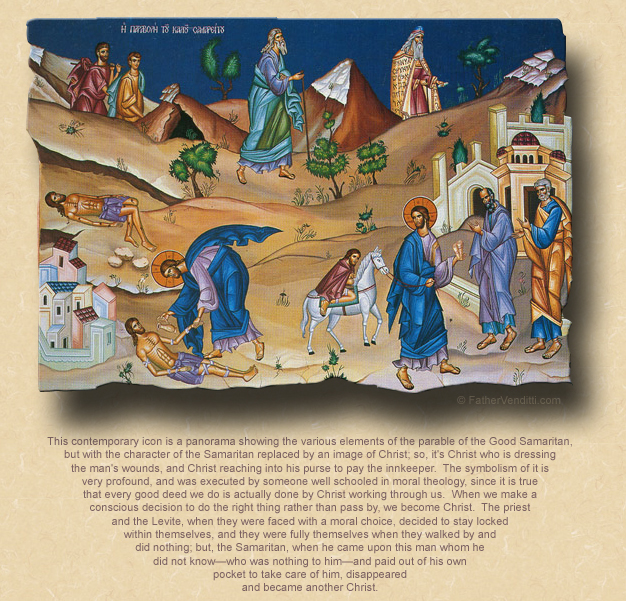

Those of you who have not visited the parish web site may not be aware that all of the homilies are made available there, usually posted sometime during the week after they are preached; and, when I post a homily I always include with it an icon illustrating the Gospel passage on which it's based. When I posted my homily on the Good Samaritan last year, the icon I posted with it was a very nice one illustrating the parable, but with a twist: it's a panoramic icon showing all the various parts of the story—the Levite passing by, the priest passing by, the Samaritan putting the wounded man on his beast—but what's really interesting is that in each scene, the character of the Samaritan is replaced by an image of Christ; so, it's Christ who is dressing the man's wounds, and Christ reaching into his purse to pay the innkeeper. Of the many icons of this parable I've seen, it's the only one I know of that does this. I'll use it again when I post today's homily.

And the symbolism of it is very profound when you think about it; and, whoever wrote this icon was well schooled in moral theology, since it is true that every good deed we do is actually done by Christ working through us. When we make a conscious decision to do the right thing rather than pass by, we become Christ. The priest and the Levite, when they were faced with a moral choice, decided to stay locked within themselves, and they were fully themselves when they walked by and did nothing; but, the Samaritan, when he came upon this man whom he did not know—who was nothing to him—and paid out of his own pocket to take care of him, he disappeared and became another Christ.

Now, last year I had given you the context of our Lord's parable, which was the animosity between the Jews and the Samaritans, which is why the Rabbi is so uncomfortable with our Lord's characterization. When our Lord asks him to evaluate the conduct of the various players in the drama, and which of them acted as a true neighbor to the man beset by robbers, he's so wrapped up in his own personal hatred for the Samaritans that he can't even bring himself to say the word; he has to fall back on a euphemism, and say, “The man who showed him compassion,” or however else it may be translated. And by doing this, the Rabbi himself becomes one of the players in the drama; he takes his place along with the priest and the Levite. He could have taken his place along with the Samaritan, in which case he would have been walking along with Jesus, but he couldn't—or, rather, he wouldn't—because he wasn't willing to let go of the animosity in his heart; and, that hatred to which he clung is what defines him. He is truly being himself, and what he is in himself is pretty ugly.

To be yourself. It's become a cliché in pop-psychology culture today. Be yourself. Be true to yourself. Strip away your masks. These are things we're told we're supposed to do. But a Christian's understanding of life has to begin at the beginning, and for us that's the beginning of the Bible in Genesis. That's where we learn that man fell from Grace, that, because of that fall, we are all conceived in sin and live out our lives beset by temptation, that we overcome temptation and live lives of virtue only through the Grace of Christ that comes to us through the Holy Mysteries. “He must increase and I must decrease,” said St. John the Baptist, and so must we all.

I don't know who wrote this icon of the parable of the Good Samaritan;—most traditionally written icons don't display the name of the iconographer—but, whoever he is, he has revealed to us an invaluable truth which we can apply to everything said to us by our Lord. Whenever we do something good, we are stepping aside and becoming, ourselves, an icon of Christ; but, when we do something bad, we are closing ourselves up, locking out Christ, and being truly ourselves in the basest possible way.

Father Michael Venditti

* Due to the "Lucan Jump," the Gospel read today is that for the 25th Sunday after Pentecost. Cf. the note appended to the Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost.

|