Life Isn't a Gift; It's a Loan.

The Twenty-Seventh Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the primary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 5: 1-7.

• Psalm 80: 9, 12-16, 19-20.

• Philippians 4: 6-9.

• Matthew 21: 33-43.

The Eighteenth Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Corinthians 1: 4-8.

• Psalm 121: 1, 7.

• Matthew 9: 1-8.

The Eighteenth Sunday after Pentecost (the Third after the Holy Cross); and, the Feast of Our Venerable Mother Pelagia.*

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• II Corinthians 9: 6-11.

• Luke 7: 11-16.**

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:14 AM 10/8/2017 —

A song, now, in honour of one that is my good friend; a song about a near kinsman of mine, and the vineyard that he had. This friend, that I love well, had a vineyard in a corner of his ground, all fruitfulness. He fenced it in, and cleared it of stones, and planted a choice vine there; built a tower, too, in the middle, and set up a wine-press in it. Then he waited for grapes to grow on it, and it bore wild grapes instead. And now, citizens of Jerusalem, and all you men of Juda, I call upon you to give award between my vineyard and me. What more could I have done for it? What say you of the wild grapes it bore, instead of the grapes I looked for? (Isaiah 5: 1-4 Knox).

That’s Monsignor Knox’s florid translation of the opening verses of today’s first lesson from Isaiah. The prophet is circumspect beyond all poetry, yet there is no mistaking his meaning. The friend of whom he sings is God, and the vineyard he plants and tends is an allegory for all the things God had done for the people He had chosen to be His own: establishing the covenant with Abraham, leading them out of bondage in Egypt, giving His law to Moses, granting them victory after victory after victory against all who tried to destroy them as a people so that they could establish a great kingdom. But the grapes the vineyard bears are not sweet, because the people had lost their faith.

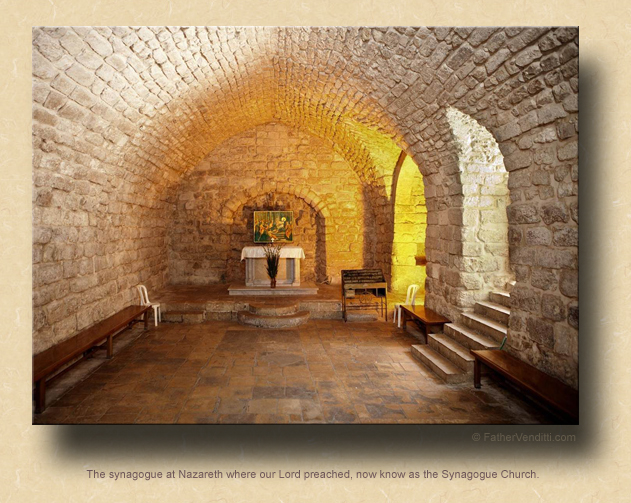

We know for a fact that our Blessed Lord knew the Scriptures well; it was for good reason that His disciples addressed him as “Rabbi.” The first sermon He gave upon returning to his home-town synagogue at Nazareth was on the Prophet Isaiah, quoting the passage from memory; so, there is no doubt that, in the parable He tells in today’s Gospel lesson, what was our first lesson from Isaiah was clearly on His mind. But, like so many of the things said by our Lord, the parable He tells has more than one meaning. On the surface, our Lord has a very definite message for His listeners, practically identical to that of the Prophet. He speaks of a vineyard which is leased out to others by it’s owner; He speaks of servants who are sent by the owner to collect the year’s harvest from the tenants, and how the servants are beaten and killed by the tenants who have forgotten that they don’t own the vineyard; and finally He speaks of a son who is sent and who is killed.  The symbolism is almost too simple: the owner of the vineyard is, of course, God the Father, who has offered His covenant—His vineyard—to the Jewish people. And when His people go astray, He sends them His servants, the prophets, to remind them that they are not the owners, that they owe an accounting of their lives to God. But the servants—the prophets—are ignored, and some are killed, as we know frequently happened in the Old Testament. And in a final act of compassion and fatherly concern, the vineyard owner, God, sends His own Son, at which point we realize our Lord is speaking about Himself. Isn’t it interesting that when our Lord speaks in the parable of how the son of the owner is killed because of the tenant’s greed, He is predicting His own death at the hands of His own people? The symbolism is almost too simple: the owner of the vineyard is, of course, God the Father, who has offered His covenant—His vineyard—to the Jewish people. And when His people go astray, He sends them His servants, the prophets, to remind them that they are not the owners, that they owe an accounting of their lives to God. But the servants—the prophets—are ignored, and some are killed, as we know frequently happened in the Old Testament. And in a final act of compassion and fatherly concern, the vineyard owner, God, sends His own Son, at which point we realize our Lord is speaking about Himself. Isn’t it interesting that when our Lord speaks in the parable of how the son of the owner is killed because of the tenant’s greed, He is predicting His own death at the hands of His own people?

The Pharisees and the Hebrew priests who were present in the Temple that day were not stupid. They knew our Lord was speaking about them; Saint Matthew, tells us as much. But what he does not tell us—what he cannot tell us—is what our Lord may be trying to say to us, today. Everything said by our Lord has a double meaning; and, while the parable of the vineyard may be, to our Lord’s historical audience, an allegory about the history of the Jewish people and the role of Christ in salvation, it also must teach us something about ourselves, and something more than just a historical lesson.

For the Lord has also entrusted to us a vineyard. He has given us new life through baptism. He has given us the Church and the sacraments as fountains of grace and life. He has given us the Gospel as a path to heaven. He has placed in our own hands the possibility of salvation and eternal life. He has sent us teachers to correct our faults, not only the prophets of old, but also the Fathers of the early Church, the saints, the martyrs, the popes. Sometimes we listen, sometimes we don’t. And the day will come when He will ask for an account of how well we have harvested the seeds that He has planted.  And if there is no fruit, that will not be His fault, but ours; for just as the vineyard owner sent his son to collect the harvest, just as the Father sent Christ our God to collect the harvest of the covenant from the Jewish people, so again the Father will send the Son as King and Judge of the world. And He will ask us to show Him the lives of purity and virtue and holiness that we have reaped from the seeds of grace He has so generously planted in us. For all of our pro-life rhetoric, the brutal fact is that life is not a gift. Life is something we have on loan from God for a while, lent to us to spread His word, serve one another in charity and cultivate in ourselves His virtues; and, at the end of everything it will have to be returned in the condition it was received when we were baptized, along with the accounting of what we have done with it. And if there is no fruit, that will not be His fault, but ours; for just as the vineyard owner sent his son to collect the harvest, just as the Father sent Christ our God to collect the harvest of the covenant from the Jewish people, so again the Father will send the Son as King and Judge of the world. And He will ask us to show Him the lives of purity and virtue and holiness that we have reaped from the seeds of grace He has so generously planted in us. For all of our pro-life rhetoric, the brutal fact is that life is not a gift. Life is something we have on loan from God for a while, lent to us to spread His word, serve one another in charity and cultivate in ourselves His virtues; and, at the end of everything it will have to be returned in the condition it was received when we were baptized, along with the accounting of what we have done with it.

In the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass we are thrust into the very presence of God. In receiving Holy Communion we are given more grace than was ever given to the prophets of old. But it is not magic. Being in the very presence of Christ our God in the Eucharist, even the act of taking Him into our souls in Holy Communion, does not compel us to do good against our will. We have to make a decision that, after we have received our Lord and go forth from this Church back out into the world, that we will live as if Christ lives in us. We have to decide whether, when others see us act or hear us speak, they will be able to see Christ in us. And if, when they see us, they see nothing different from what they see in those around us who know not Christ, then we must ask ourselves, “What was the point?”

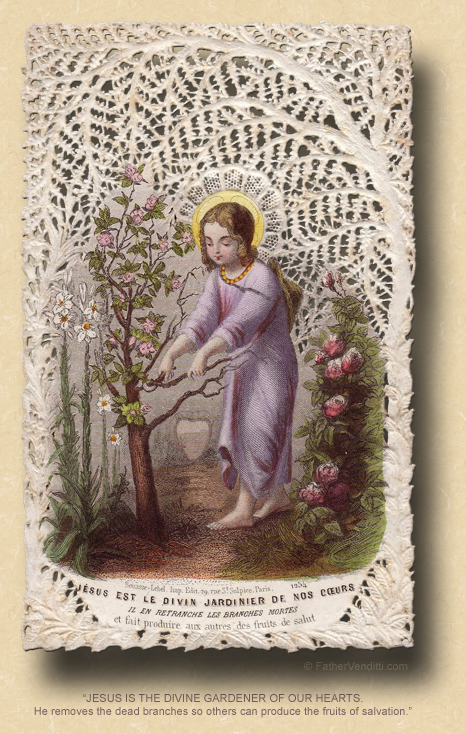

We’ve had a particularly active and tiring weekend here at the Shrine, so today’s homily is brief. All I ask of you today is to be mindful that Christ, once again, will plant the seed of His grace into our souls today when we receive Him in Holy Communion. Let us not allow that seed to wither and die in a parched, arid land. Let us water it with virtue, tend it with prayer, prune it with sacrifice and mortification, so that when the vineyard Owner finally calls us home, we can return to Him a rich harvest.

* Today is called "The Third Sunday after the Holy Cross" because "The Sunday after the Exaltation" (Sept. 17th) is considered part of the Postfestive period of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, and thus part of the feast itself. Following the feast and postfestive period of the Holy Cross (Sept. 14th through 21st), the Greek Church actually labels these Sundays as “Sundays after the Holy Cross” and begins to number them accordingly, calling today "The Third Sunday after the Holy Cross," while the Ruthenian and Russian Churches continue to number them as "Sundays after Pentecost" (though in some older Ruthenian typicons the Greek custom is observed). The historical context of this custom was the Greek practice of marking the birthday of the Emperor Augustus on September 23rd, which they regarded as the first day of the Church year. It was not until the fall of the empire that the new year observance was moved to Sept. 1st throughout the Churches of the Byzantine Rite.

Palagia was born in Antioch toward the second half of the fifth century. After years spent in luxury and pleasure, she accepted baptism and retired to Mount Olivet, where she died after a life of penance.

** The four Gospels are all read in their entirety in the Byzantine Churches, and the reading of each begins with a great feast. The Gospel of St. John begins with the Feast of Feasts, Pascha, and is read until Pentecost. The Gospel of St. Matthew begins with Pentecost, and is read until the Feast of the Holy Cross, after which the Gospel of St. Luke is read all the way through until the Great Fast; but, because the Divine Liturgy is offered only on Saturday and Sunday in the Great Fast, the left-over passages are read in the last six weeks of the Matthean and Lucan cycles. This is why the Byzantine Churches begin the reading of Luke’s Gospel on the Sunday after the Holy Cross no matter where they are in the cycle of "Sundays after Pentecost." The Epistles, on the other hand, are read continuously without any adjustment, creating a discrepancy between Epistle and Gospel. This year, there is a discrepancy of two weeks until Dec. 28th. In the Byzantine Churches, this is commonly called "the Lucan Jump." Thus, today, the Epistle sung is the one for the Eighteenth Sunday, and the Gospel the one ordinary sung on the Twentieth Sunday.

|