The Patron Saint of the Bitter and Angry.

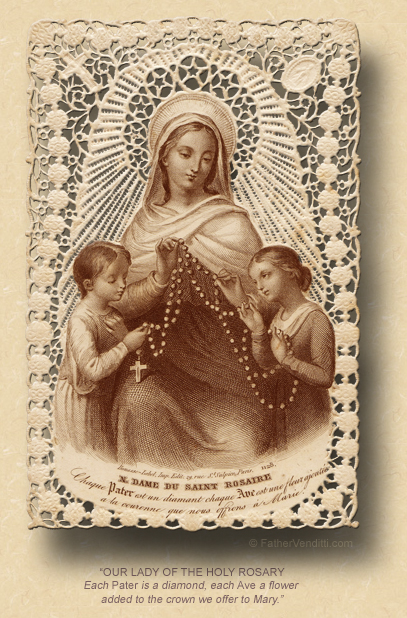

The Memorial of Our Lady of the Rosary.

Lessons from the primary feria for the Twenty-Seventh Monday of Ordinary Time, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Jonah 1: 1—2: 1-2, 11.

• [Responsorial] Jonah 2: 3-5, 8.

• Luke 10: 25-37.

|

…or, from the proper:

• Acts 1: 12-14.

• [Responsorial] Luke 1: 46-55.

• Luke 1: 26-38.

…or, any lessons from the common of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

|

The Second Class Feast of Our Lady of the Holy Rosary; and, the Commemoration of Saint Mark, Pope & Confessor.*

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Proverbs 8: 22-24, 32-35.

• Psalm 44: 5, 11-12.

• Luke 1: 26-38.

|

If the Mass for the feast is a High Mass, and a Low Mass for the commemoration is taken,** lessons from the common "Si díligis me…" of One or Several Holy Popes:

• I Peter 5: 1-4, 10-11.

• Psalm 106: 32, 31.

• Matthew 16: 13-19.

|

FatherVenditti.com

|

7:32 PM 10/7/2019 — The Memorial of Our Lady of the Rosary, which we celebrate today, was originally established as a second class feast by Pope Saint Pius V locally in Rome in thanksgiving for the decisive defeat of the Turks at the battle of Lepanto in 1571, and was extended to the Universal Church in thanksgiving for their subsequent defeat at the battle of Belgrade in 1716; and, in the extraordinary form, it is still observed as a feast of the second class. 7:32 PM 10/7/2019 — The Memorial of Our Lady of the Rosary, which we celebrate today, was originally established as a second class feast by Pope Saint Pius V locally in Rome in thanksgiving for the decisive defeat of the Turks at the battle of Lepanto in 1571, and was extended to the Universal Church in thanksgiving for their subsequent defeat at the battle of Belgrade in 1716; and, in the extraordinary form, it is still observed as a feast of the second class.

Most historians trace the Rosary's origin to 9th century Ireland. Without cities of any appreciable size in which to establish dioceses, Saint Patrick had set up the church in Ireland around a network of monasteries; and then, as now, the liturgical life of monasteries centered around the Divine Office, most of which consists of the chanting of the 150 Psalms. Lay people living near the monastery saw the beauty of this form of prayer; but, because very few people outside the monasteries could read, lay people had to find a way to adapt this prayer for their own use. By the year 800, it was common practice in Ireland to recite 150 Our Fathers in place of the 150 psalms.

Yesterday, the sixth of October, would have been Memorial of Saint Bruno had it not fallen on a Sunday. He was the holy founder, in the 10th century, of the Carthusians, with whom I spent some time considering a vocation to that monastic community of hermits. It was a Carthusian monk, Henry of Kalkar, in 1365, who first suggested the practice of reciting 150 Hail Marys in groups of ten, separated by an Our Father. Another monk of the same community, Dominic the Prussian, in 1409, wrote a book which attached thoughts for mediation on the lives of our Lord and our Lady to each group, thus creating what we call today the Mysteries of the Rosary. It wasn’t really until then that the Dominicans entered the picture, and it was left to the Dominican friar, Alan of Rupe, to popularize devotion to the Rosary as a means of meditation throughout the world.

The addition of an additional set of five mysteries to the Rosary by Pope Saint John Paul II—recitation of which he said was purely optional—had the unfortunate effect of blurring the link of the Holy Rosary to the Psalter, as it would no longer correspond to the 150 Psalms; and, in his 2002 Apostolic Letter, Rosarium Virginis Mariæ, in which he first introduces us to the Mysteries of Light, he mentions that, while the Rosary has it's origin in the Psalter, it has long taken on a life of its own, and is now much more than a simple replacement for praying the Psalms. Indeed, in this day and age, in which most people can read, those who wish to pray the Psalms can do so without having recourse to a replacement.

Thus, the genesis and development of the Holy Rosary in the life of the Church is a beautiful example of how the love of the faithful for our Lord and our Lady can blossom into an integral part of the life of the whole Church; and, now we could hardly imagine ourselves without it. The fact that the Mother of God Herself, at Fatima, requested that we meditate on the Mysteries of the Rosary as part of our Five First Saturdays observance shows how even the Heavenly Church responds to the Church Militant, just as our Lord said: “…whatever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven; and whatever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.” (Matt. 16: 19 Knox).

The first lesson at Holy Mass today and tomorrow are from the Book of the Prophet Jonah, and I didn’t want to let Jonah slip by without some mention, especially since I won’t be with you the next three days.

The Prophet Jonah gets short shrift in the Roman Missal, probably because his story is one of the shortest books of the bible: 48 verses divided into four very brief chapters. The date of its composition is hard to pin down: anywhere between the eighth to the first century BC; but, the style of the Hebrew is the same as that used in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, which would put it somewhere in the fifth century.  Equally contested is the question of whether Jonah was a historical person, or whether the book is a parable. There are certainly a lot of Old Testament parables which do not pretend to be historical accounts; but, they occur mostly in the first five books of the Bible, and don't contain the kind of biographical data about the subject that we find in Jonah. Our Lord Himself seems to refer to Jonah as a symbolic person when, in both the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, He refers to what He calls “the sign [or symbol] of Jonah,”*** but that's not conclusive by any means. Equally contested is the question of whether Jonah was a historical person, or whether the book is a parable. There are certainly a lot of Old Testament parables which do not pretend to be historical accounts; but, they occur mostly in the first five books of the Bible, and don't contain the kind of biographical data about the subject that we find in Jonah. Our Lord Himself seems to refer to Jonah as a symbolic person when, in both the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, He refers to what He calls “the sign [or symbol] of Jonah,”*** but that's not conclusive by any means.

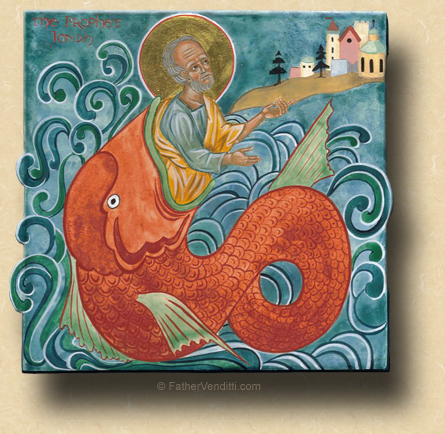

Of course, whether legend or fact, whichever it may be, the story of Jonah we all know, at least the outline of it: Jonah is a reluctant prophet. God commands him to go the city of Nineveh and preach to them because they had become wicked in God's eyes; but, Jonah wants none of it, and instead goes to Joppa and catches a boat for Tharsis thinking that God can't find him in Tharsis (the Bible doesn't say that Jonah was a particularly bright man). The ship gets caught in a typhoon, and the captain, upon discovering that Jonah is a Jew, pleads with him to call upon his God to save them, but Jonah doesn't want to open up any lines of communication with God; he's trying to run away from God. So, the crew, in a stereotypical fit of seafaring superstition, conclude that the reason they're caught in a typhoon is because they're harboring a fugitive from God, so they throw him overboard. God causes Jonah to be swallowed up by a great fish, in whose belly he languishes for three days and three nights (in a prefiguring of our Lord's three days in the tomb), where he finally breaks down and calls upon God to save him; and, as our first lesson today ends, the fish burbs him up on the beach—ironically, not far from the city of Nineveh—and God, once again, repeats His command for Jonah to go there, and this time he does. He tells the Ninevites that they have forty days to repent of their evil ways or else God will destroy them, but it doesn't take forty days; after only one day of preaching, the whole city is converted, and even the king of Nineveh sheds his robes and covers himself in sackcloth to do penance.

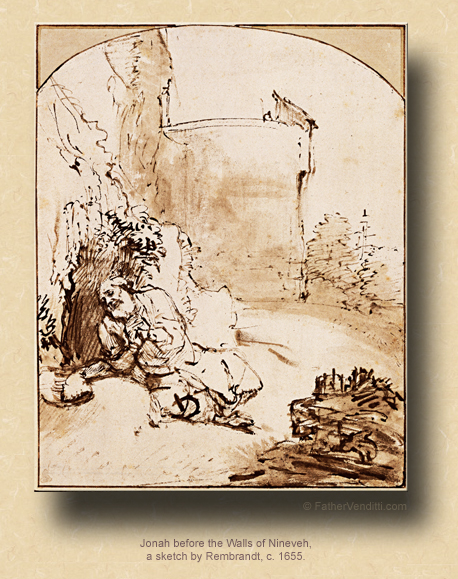

And this is where the story gets interesting, because Jonah, after all he had been through, decided that he was entitled to see some fireworks. Now, from the outset, Jonah is portrayed as a bitter and angry man;—we have no idea why—and, while you'd think that his experience in the belly of the fish would have cured him of that and made him a little more humble, it didn't. He tries to tell God that the reason he ran away in the first place was because he suspected all along that God was a soft touch and wasn't going to follow through on His threat against the city. He completely glosses over the fact that the Ninevites made a very dramatic repentance. He sits down under a tree where he can see the city to see if God will destroy it after all, and when it isn't destroyed he wants to die. God reaches out to Jonah and wants to dialog about it, but Jonah refuses to talk to Him.  There’s a little more after that which ties the whole thing up better than I have here, but that's pretty much where the book ends. There’s a little more after that which ties the whole thing up better than I have here, but that's pretty much where the book ends.

It's an odd story, and its abrupt ending causes us to want to ask some questions, such as why Jonah feels the way he does at the end. There might be a historical reason: Nineveh was the capitol of the Assyrian Empire, which was a long-time enemy of Israel; so, maybe Jonah was angry that God would even give the Ninevites a chance to repent.

The story of Jonah is, of course, a lesson about God's mercy, but there's more to it than that. Jonah is not an uncommon type of person. He's angry at the world, and for reasons that may or may not make sense to anyone but him. And, while he goes through the motions, giving lip-service to the idea that he wants things to change, in reality he doesn't; because, if things were to change, he would have nothing more to be angry about, and wouldn't know what to do with himself. Most of us have probably known someone like that, or even lived with someone like that. And, as distasteful as it sounds, there are times when we're all tempted to go down that acrimonious road. Maybe we're older now, and most of our friends are gone, and we feel that our families don't pay enough attention to us; our children have families of their own now, and we're no longer the center of their attention. Things are not what they used to be: the neighborhood has changed, the parish has changed, nothing is familiar anymore, coupled with all the usual aches and pains that come with growing old, and all the things we used to be able to do that we can't anymore.

There is a remedy to all this, of course, and that's prayer. That is what I think is the real message of the Book of Jonah. It ends on a low note because Jonah, in his bitterness, cuts off his dialog with God. It would be nice to have the story end up a redemption story, like the Book of Job: bad things happen to Job just like they do to Jonah, but Job never stops praying; and, because he never stops praying, he and God are reconciled. Both books are relatively short (Job is a little longer), they're both very similar, but they end in completely different ways; and, there's a reason why it's important that the Book of Jonah ends the way it does. Life is often disappointing, and how we respond to that disappointment is crucial. In the midst of all his tragedies, Job never stopped praying, never stopped trusting that God would, somehow, make everything alright in the end, which He did. Jonah did stop praying and, as a result, his anger became his only companion. In the end, that was all he had left.

The moral of the story, of course, is that the choice is really up to us. Almighty God, in His permissive will, allows crosses to come our way for reasons that remain hidden to us—sometimes as atonement for our sins, sometimes as reparation for the sins of others, sometimes to humble our wills in preparation for some great task He has for us to do in the future—and how we respond to those crosses is important. But we’d never respond in any way at all if we were to stop talking with God.

* Pope St. Mark, the successor of St. Sylvester, occupied the Holy See for a few months, and died in the year 336.

** In the extraordinary form, when a commemoration falls on a second class feast, and the Mass for the feast is a High Mass, a subsequent Low Mass for the commemoration may be taken, provided there is a genuine need for a second Mass. In this case, no mention of the commemoration is made at the High Mass.

If, on the other hand, there is no High Mass this day, and the Mass or Masses for the feast are all Low Masses (as would be the case in most parishes), then a Mass for the commemoration is not permitted, and the commemoration is made by an additional Collect, Secret and Postcommunion added to those of the feast.

*** In the Greek, Ἰωνᾶ, genitive of the epexegetic Ἰωνᾶϛ: not the sign that Jonah either received or gave, but the sign or symbol that Jonah was in himself.

|