12:38 PM 10/7/2014 — I've come across a real gem (or, rather, a friend of mine came across it and alerted me to it): a letter from 2003, written by then Cardinal Ratzinger, in answer to a letter requesting wider permission throughout the Latin Church for the use of the Missal of John XXIII.

Dear Dr. Barth!

My heartfelt thanks for your letter of April 6, which I didn't have time to answer until now. You're asking me to lobby for a wider permission of the old Roman Rite. As you well know, I am very open to such requests, as my efforts towards this end are widely known by now.

The entire letter was once available at a blog called “The Cafeteria is Closed,” but is no longer available there. This "wider permission" of which the future pope speaks was granted, as we know, by himself some years later, in the moto proprio, Summorum Pontificum. For those who have not read it, basically, it says that any priest of the Roman Catholic Church can celebrate Holy Mass according to the missal of Pope Saint John XXIII, promulgated in 1962. That missal was the last revision of the so called “old Latin Mass” of Pope St. Pius V (promulgated on July 14, 1570), prior to the adoption of the current missal of Pope Paul VI currently in use. In the motu proprio, the former Holy Father corrects a misconception: that the 1962 missal was somehow forbidden by Vatican II. This was never so, said Pope Benedict, and to emphasize this point he decreed that any Roman Catholic priest can use this missal for offering a private Mass without the need to seek permission from anyone. Moreover, the faithful, if they wish, may attend these Masses. Priests in parishes may also use this missal for parish Masses on weekdays, and for one Mass on Sundays and Holy Days, if there are people in the parish who wish it.

Of course, at the time he wrote the above-mentioned letter, Card. Ratzinger had no idea that he would one day be in a position to grant this request, in spite of the fact that his "efforts toward this end are widely known by now." It's interesting how, in 2003, he viewed the prospects from the point of view of someone who clearly never envisioned that he would one day be pope:

Whether the Holy See will permit the old Rite "once more worldwide and without limitations”—as you desire and have heard rumors to that effect—I cannot simply answer, let alone confirm. The dislike for the traditional liturgy, which is called, with contempt, "pre-conciliar," is still very strong among Catholics who've been drilled to reject it for years. Additionally, there would be strong resistance on the part of many bishops.

Is there a tinge of impatience in the future pope's words? That anyone would dismiss a liturgical tradition out of hand by calling it "pre-conciliar" is infuriating enough. As one bishop I knew, now deceased, said in response to someone who accused him of being pre-conciliar, "So was the Last Supper."

The notion that 1965 (the date of the close of the Second Vatican Council) marked the creation of a totally new Church, replacing anything and everything that came before it, is surprisingly well entrenched among many priests, bishops and lay people today. In fact, I've heard it stated in almost exactly those same words by a priest who came to the seminary to preach a day of recollection to us some thirty years ago: "In 1965, Pope Paul VI created a new Church." I was not the only person taken aback, as many of us were under the impression that Jesus Christ had established the Church; and, since there had been some twenty ecumenical councils before Vatican II, none of which claimed to have first destroyed then recreated the Church of Christ, we wondered if we were not being admonished to believe we were living in a time of new Divine Revelation.

Of course, we are not. The Second Vatican Council, as important as it is, is no more important than any of the other Ecumenical Councils which came before it; it's decrees can no more cancel those of Vatican I or the Council of Trent than Nicea II could cancel Nicea I, or the Council of Jerusalem cancel the Gospel. It's just that we suffer from "historicentrism," the disease that causes us to think that our generation is not only the most advanced and worthy to date, but the most advanced and worthy ever, presuming that future generations will no doubt look to us for all their answers.

Back in 2008, I ran a blog in which I offered a series of posts on the liturgy and, in one of them, I suggested that, if there was a general reform of the Roman Liturgy, some priests would leave the priesthood, saying what many old timers said after the Council as they reluctantly accepted early retirement: "This isn't the Church for which I was ordained." And, when they did, the same thing would be true now as it was then: "Jesus Christ, yesterday, today, and the same forever!" (Heb. 13: 8). The suggestion that some priests would react to a “re-reform” of the Roman Liturgy by setting their priesthood aside may seem hyperbolic to some, but is it so far fetched? The operative question for any priest whose ministry has been exclusively post-conciliar is this: does he view his style of ministry, his personal spirituality, his manner of celebrating the Liturgy, indeed, his faith as emanating from—and being formed by—a participation in a ministerial priesthood that is one with Christ, His apostles, and every priest who has come before him in an unbroken line of perfect sacramental and historical continuity; or, does he see his style of ministry, his personal spirituality, his manner of celebrating the Liturgy, his faith as somehow defined and formed by a mile-marker in the road of Church history called Vatican II, with himself on one side of that marker, and everything and everyone who came before it as being on “the other side"?

Consider this real-life example: I know two priests—good priests—who have a quirk which annoys me no end (they don’t know one another, so it’s a quirk that each developed on his own). At Mass, during the Anaphora (“Eucharistic Prayer”), they pray the prayer while maintaining intense and continual eye-contact with the congregation. Consider the implications of this seemingly innocent idiosyncrasy: the prayer itself is addressed to the Father; after the consecration, our Lord is present in a substantial way on the altar before them; the Father is, in fact, hypostatically united with the Son in the Eucharist. Shouldn’t one be looking at the person to whom one is speaking? What does it mean, then, when the priest is looking at the people?

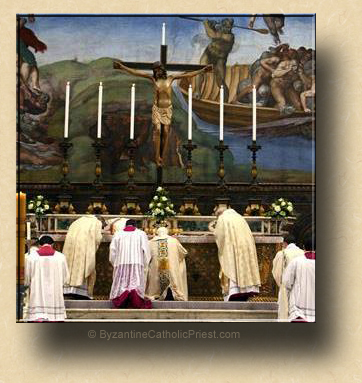

Back in 2008, then-Pope Benedict celebrated Mass in the Sistine Chapel according to the Novus Ordo, versus Dominum. that is to say, “facing the Lord.” To repeat: he was not celebrating the "traditional Latin Mass," but the "new Mass." Knowing that this would raise an eyebrow or two, he explained himself by recalling a long-forgotten practice of the early Church:

In the liturgy of the ancient Church, after the homily, the Bishop or the presider of the celebration, the main celebrant, said, "Conversi ad Dominum." Then he and all [others] stood up and turned towards the East. All wished to face towards Christ. Only if converted, only if in this conversion towards Christ, in this common facing of Christ, we may find the gift of unity.

I had posted a photo of the celebration on my old blog. Show that photo to the two priests mentioned above, and I’ll bet you dinner at a finer eating establishment what the reaction would be: “Why does he have his back to the people?” without any thoughtful consideration of what this particular prevarication might mean. To put it another way, ask them if (a) the Holy Father has his back to the people, or (b) he is more perfectly uniting himself with the people as they all face the same way, conversi ad Dominum (“let us turn toward the Lord”)? The very question would bounce off their brains as if spoken in some foreign tongue; and the former Holy Father’s explanation would make no more sense than if he were speaking to them in Martian.

I had posted a photo of the celebration on my old blog. Show that photo to the two priests mentioned above, and I’ll bet you dinner at a finer eating establishment what the reaction would be: “Why does he have his back to the people?” without any thoughtful consideration of what this particular prevarication might mean. To put it another way, ask them if (a) the Holy Father has his back to the people, or (b) he is more perfectly uniting himself with the people as they all face the same way, conversi ad Dominum (“let us turn toward the Lord”)? The very question would bounce off their brains as if spoken in some foreign tongue; and the former Holy Father’s explanation would make no more sense than if he were speaking to them in Martian.

Now, keep in mind that these two priests—as I said—are good priests, desirous in every way of doing what is right and proper. So, what motivates their eye-contact with the people during a prayer addressed to the Father through the Eucharistic Lord on the altar? Simple. Despite their good intentions and personal devotion, they were malformed: while they may intellectually know that the Mass is a sacrifice, their training and their whole ministry to date has been within the milieu, spoon-fed to them in the seminary, that the Mass is a meal, and that its focus is not the God on the altar, but the God who dwells in all of us. They themselves would never say it that way, and they might even recognize it as heresy; but it's in their pores and you can't boil it out of them.

Now, let's go a step further:

During my years serving in the Byzantine-Ruthenian Catholic Church, I often had occasion to invite a Roman Catholic priest to concelebrate the Divine Liturgy with me in my church—occasions like funerals or weddings or what-have-you. On one particular occasion, a funeral, the priest slithered into my sacristy with a chip on his shoulder. Did I say chip? It was more like a log. After having first furrowed his brow at my icon screen (which he no doubt interpreted as a communion rail on steroids), he turned to squint at my altar which, of course, is versus Dominum, with the Blessed Sacrament reserved right on it. What followed, in the few minutes we had before Liturgy one wouldn't exactly characterize as a tirade; he didn't rave, or foam at the mouth, or even raise his voice; he was polite, but he wouldn't stop. He just couldn't accept things as he found them, even in a church that was of a different tradition from his own. He had to weigh in on anything and everything that disturbed his "world view," be it the orientation of the Holy Table, or the "static vs. dynamic" presence of Christ in the Eucharist. "Goodness," I thought. "What's he going to do when he finds out that practically half of the Eucharistic Prayer is said silently by the priest? Will he pull a gun?"

Well, he didn't, you'll be glad to know, and the rest of the morning passed more or less uneventfully (though when it was all over he bolted from church like a man on fire, probably to go shower the stench of incense from his body). I mention him because he contrasts with the two priests previously mentioned in some very important ways. First, he's older, ordained before the Council, but "enlightened" after it. Second, he is not "desirous in every way of doing what is right and proper," but rather views himself as the "meter" of what is right and proper (it never ceases to amaze me how some men, who were already priests during the Council, have somehow convinced themselves that they were there and actually had a hand in it). Had he been visiting an Orthodox church, he probably wouldn't have said anything, and would have been perfectly content in the knowledge that I and my flock were separated brethren, posing no threat to the balance of the universe. But we were not. We were Catholics, belonging to the same Church as himself. This, of course, is a problem because it means that the same magisterium that he thinks mandated all the gobbledegook that guides his life, supported and promoted us.

What to do, what to do??? And he is the priest referred to above: the one who, if faced with a general and comprehensive reform of the Western Liturgy—to use Cardinal Ratzinger's words—"standing wholly in the legacy of the traditional Rite," would most likely opt for an early retirement rather than re-wire his brain to accept something so foreign to his own "personal faith." For him, Vatican II wasn't one council among many; it was a "new Pentecost"—and not just a new Pentecost, but one which cancels the previous one. For him, the Church is community (which, of course, it is), but that's all it is. Her Liturgy does not carry a duel purpose of sanctifying and uniting; it's only one of those, and he's sure he knows which one. Based on the way he's re-tooled his priesthood, his approach to the liturgy eschews any concern for validity or the historical significance of the actions he performs at the altar, and instead focuses on whatever in the liturgy can be made to appeal to the emotional. He could never, for example, celebrate the Eastern Liturgy or celebrate, for that matter, the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Liturgy, since the lack of eye-contact with his brothers and sisters would make the whole thing meaningless to him. The liturgical act, for him, is not so much an encounter between the worshipers and God as it is between the priest and his flock. His purpose in the sanctuary is not so much salvific as it is therapeutic, with the goal of the liturgical act being not the transmission of grace but the healing of emotions: a wedding is not a ratification of a covenant with God, but a celebration of love; a baptism is not the cleansing of Original Sin and the restoration of Sanctifying Grace, but a celebration of life; confession is not the acknowledgment and forgiveness of sins, but a celebration of affirmation and reconciliation; a funeral is not an appeal to God to speed the soul on its journey and keep it safe until the final Resurrection, but grief counseling for the bereaved; and the Eucharist is not the Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of Jesus Christ offered for our sins on the Altar of the Cross, but a gathering of fellowship around the table of the Lord in which we find our "true selves" in communion with one another.

Believe or not, I do not think any of this is an exaggeration, and this brand of priest is much more common than any of us would like to admit. Summorum Pontificum is not simply an annoyance to him; it's a challenge to his religion. And if the comprehensive reform hinted at in Card. Ratzinger's 2003 letter were to ever occur, he would lose his faith, because it wouldn't just be about rubrics; it would be about the very essence of the Christian Faith of which the Liturgy is the primary expression, and it would no longer express what he believes. He might, for a time, hold out hope that some future pope will come along to undo the damage done to the Holy Spirit who, after all, told us to face the people at Vatican II (in much the same way that so many nuns lamented, during the last pontificate, that they won't be priests "under this pope"); but, when the correction doesn't come, he'll leave. He'll have to. And he'll be thoroughly convinced that it was the Church who left him.

The sad part is, it won't really be his fault. The Church, returning to its roots, will simply be speaking a language he doesn't understand, preaching a religion that he no longer believes.