The Patron Saint of the Normal (or Those Who Want to Be).

In the United States & Canada:

The Twenty-Sixth Friday of Ordinary Time; the Memorial of Saint Bruno, Priest; or, the Memorial of Blessed Marie Rose Durocher, Virgin.*

Lessons from the primary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Baruch 1: 15-22.

• Psalm 79: 1-5, 8-9.

• Luke 10: 13-16.

|

If a Mass for the Memorial of the Priest is taken, lessons from the feria as above, or from the proper:

• Philippians 3: 8-14.

• Psalm 1: 1-4, 6.

• Luke 9: 57-62.

…or, any lessons from the common of Holy Men & Women for a Monk, or the common of Pastors for One Pastor.

|

|

If a Mass for the Memorial of the Virgin is taken, lessons from the feria as above, or, any lessons from the common of Virgins for One Virgin.

|

|

Outside the United States & Canada:

The Twenty-Sixth Friday of Ordinary Time; or, the Memorial of Saint Bruno, Priest.

Everything as above, excluduing what is indicated for the Memorial of the Virgin.

|

The Third Class Feast of Saint Bruno, Confessor.

Lessons from the common "Os justi…" of a Confessor not a Bishop, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ecclesiasticus 31: 8-11.

• Psalm 91: 13-14, 3.

• Luke 12: 35-40.

The Seventeenth Friday after Pentecost; and, the Feast of the Holy & Glorious Apostle Thomas.

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fourth from the menaion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Colossians 1: 24-29.

• I Corinthians 4: 9-16.

• Luke 7: 17-30.

• John 20: 19-31.

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:04 AM 10/6/2017 — Being that today is First Friday, we will observe our custom of exposing the Blessed Sacrament at the end of Holy Mass, pray together the Litany of the Sacred Heart, after which I’ll be happy to return to the confessional for anyone who still needs to confess, having Benediction at 1:30. During your quiet time with our Blessed Lord, I ask you offer a prayer for all those who have died and who are still suffering as a result of the recent tragedy. 8:04 AM 10/6/2017 — Being that today is First Friday, we will observe our custom of exposing the Blessed Sacrament at the end of Holy Mass, pray together the Litany of the Sacred Heart, after which I’ll be happy to return to the confessional for anyone who still needs to confess, having Benediction at 1:30. During your quiet time with our Blessed Lord, I ask you offer a prayer for all those who have died and who are still suffering as a result of the recent tragedy.

But October 6th is always a special day for me, because today we are observing the Memorial of Saint Bruno. If you haven’t been here before on this day, I’m guessing, have not heard of him, nor have any particular devotion to him—just another obscure medieval saint on the Roman Calendar. Those who have been with me here for a long time know who he is and why I have a special devotion to him.

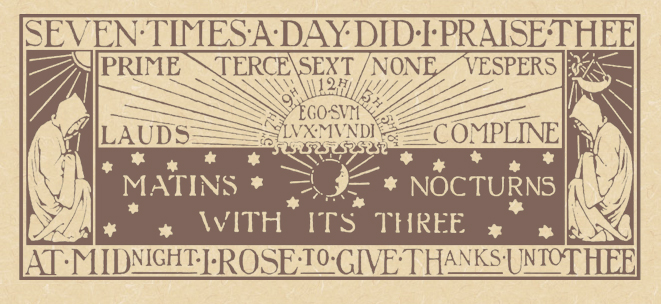

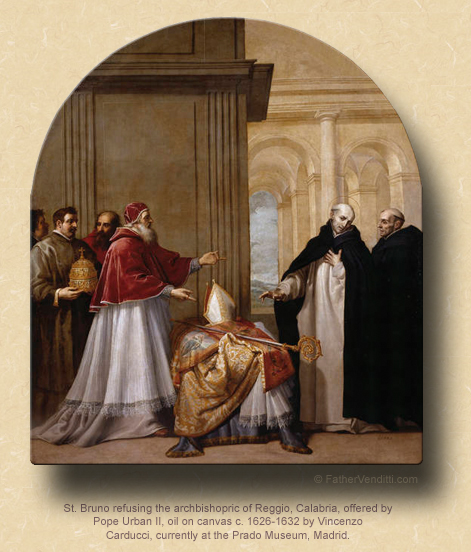

When I was younger, I had an inkling to try my hand at the monastic life. I had tried my hand at the seminary right after high school and it didn’t work out, and I ended up leaving the seminary after a couple of years; so, I thought I would escape from it all into the seclusion of a Carthusian monastery. Now, the Carthusians, founded by Saint Bruno in the 11th century in France, are often regarded by people as the strictest order of monks in the world, even though in reality they're not. Each of the monks lives more or less like a hermit, coming together only twice a day as a community: once for Holy Mass and once at midnight for the Night Office. The rest of the time they spend alone, even taking their meals by themselves in their cells. They are vegetarians and, during Lent, they even shun dairy products, eating only vegetables.

Most people, when they think of monasticism in the Western Church, typically think of Saint Benedict and the collection of religious communities that follow the Benedictine tradition, of which there are essentially three: the Benedictines, the Cistercians and the Trappists (whose real name is the Cistercians of the Strict Observance). All of them follow the Rule of Saint Benedict in one form or another, which many people think of as the only monastic rule in the Western Church. The Carthusians, founded by Saint Bruno, are not part of that tradition, they do not follow the rule of Saint Benedict, and spawned from a completely different approach to monasticism, one that was much more ethereal and mystical. No one hears about them because they avoid contact with the outside world; so, whereas some Benedictine monasteries will sometimes run colleges or high schools, or some Benedictine monks will sometimes go out on Sunday to help in parishes, the Carthusians don't do that. They don't write spiritual books for people to read, and they don't even write letters to members of their families; once you take vows in a Carthusian monastery you are dead to the outside world.  They call their monasteries “charterhouses”; they never call their houses “abbeys,” and there is no priest called an “abbot” in the charterhouse; each charterhouse elects a prior who takes care of the administrative affairs of the monastery, but other than that each monk is considered equal. There are Carthusian nuns as well, and their houses operate in the same way. Not every Carthusian monk is a priest, but all the monks assist or offer Holy Mass twice a day: they join together at a community Mass in the charterhouse church, then right after that each priest says his own private Mass in a private chapel alone, with one of them offering a second Mass for those monks who are not priests in what’s called the “Brothers’ Chapel.” Everything is done in Latin, and they use their own rite of Mass, called the Carthusian Rite. Pope Blessed Paul VI, following the Second Vatican Council, granted them an exemption from the liturgical reforms which followed the Council, just as Pope Saint Pius V had done following the Council of Trent; so, their liturgy today is exactly as it was in the eleventh century. It is, in fact, the last surviving form of the Roman Rite from before the Council of Trent that's still in use. Its structure is somewhat different from both the ordinary and extraordinary forms in use today: the vesting of the priest takes place at the altar and is considered part of the Mass itself; the offering of bread and wine is done together, with the paten on top of the chalice and carried around the altar as the offering prayers are recited; the Canon is mostly silent; the sign of peace is exchanged only on Sundays and feasts through the kissing of an image of the Lamb before the offering prayers; and, at low Mass, those in attendance kneel throughout the entire Mass except for the reading of the Gospel. Inasmuch as their liturgical tradition is frozen in the 11th century, long before the Cult of the Blessed Sacrament developed, there is no such thing as Eucharistic Adoration or Benediction. In the Divine Office, the entire Psalter is recited in the course of each day. The Eucharist is reserved in a niche behind the altar of the main church, but in a very unobtrusive way. There was never an altar rail or rood screen in a charterhouse church; and, there is no gallery for outsiders to attend as in most Benedictine monasteries, as outsiders are never permitted. They call their monasteries “charterhouses”; they never call their houses “abbeys,” and there is no priest called an “abbot” in the charterhouse; each charterhouse elects a prior who takes care of the administrative affairs of the monastery, but other than that each monk is considered equal. There are Carthusian nuns as well, and their houses operate in the same way. Not every Carthusian monk is a priest, but all the monks assist or offer Holy Mass twice a day: they join together at a community Mass in the charterhouse church, then right after that each priest says his own private Mass in a private chapel alone, with one of them offering a second Mass for those monks who are not priests in what’s called the “Brothers’ Chapel.” Everything is done in Latin, and they use their own rite of Mass, called the Carthusian Rite. Pope Blessed Paul VI, following the Second Vatican Council, granted them an exemption from the liturgical reforms which followed the Council, just as Pope Saint Pius V had done following the Council of Trent; so, their liturgy today is exactly as it was in the eleventh century. It is, in fact, the last surviving form of the Roman Rite from before the Council of Trent that's still in use. Its structure is somewhat different from both the ordinary and extraordinary forms in use today: the vesting of the priest takes place at the altar and is considered part of the Mass itself; the offering of bread and wine is done together, with the paten on top of the chalice and carried around the altar as the offering prayers are recited; the Canon is mostly silent; the sign of peace is exchanged only on Sundays and feasts through the kissing of an image of the Lamb before the offering prayers; and, at low Mass, those in attendance kneel throughout the entire Mass except for the reading of the Gospel. Inasmuch as their liturgical tradition is frozen in the 11th century, long before the Cult of the Blessed Sacrament developed, there is no such thing as Eucharistic Adoration or Benediction. In the Divine Office, the entire Psalter is recited in the course of each day. The Eucharist is reserved in a niche behind the altar of the main church, but in a very unobtrusive way. There was never an altar rail or rood screen in a charterhouse church; and, there is no gallery for outsiders to attend as in most Benedictine monasteries, as outsiders are never permitted.

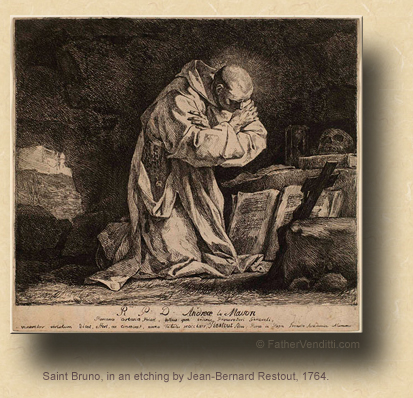

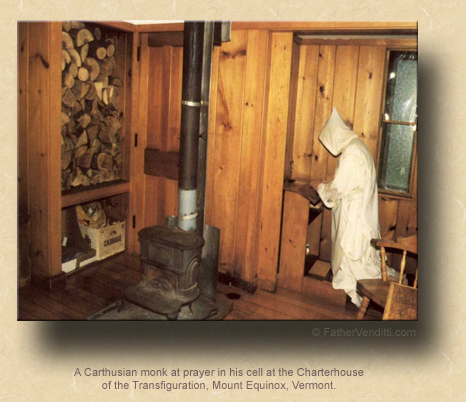

You can't visit a Carthusian charterhouse; the only way to see the inside of one is to express an interest in joining them, in which case they will invite you to visit them for a month, which is how I got inside one. The only charterhouse in this country is in Vermont, and I spent a month with them back in the late '70s. The only heat in the charterhouse is in the form of wood-burning stoves, and each monk is required to chop his own wood. You don't have to cook your own meals, and the monk who prepares the food delivers it to each cell and puts it in a little turn-stall next to the door, then rings a bell to let you know your food is ready to be picked up. Since each monk eats alone in his cell, there is no community chapter followed by breakfast, as in the Rule of Saint Benedict, except on Sundays.  Each monk sleeps in what amounts to a coffin, on a mattress filled with straw, the same coffin in which he will one day be buried; and, each night at midnight, the procurator of the house presses a button in his office which causes a buzzer next to your head to go off, to call you to church for the night office—the first couple of nights I was there I nearly hit the cealing;—there is a similar button next to your bed which you press to confirm you're awake and on the way. The night office lasts about forty minutes or so, then you go back to bed until six, when you have to get up and say your morning prayers privately in your cell before going to church again for the first Mass. After the Masses, it's out to the fields to tend to the crops, since the charterhouse grows all its own food and is self-sufficient. You take a break at noon for lunch and to say your noon day prayers, then back to work until it's time to return to your cell for evening prayers and then to bed. Each monk sleeps in what amounts to a coffin, on a mattress filled with straw, the same coffin in which he will one day be buried; and, each night at midnight, the procurator of the house presses a button in his office which causes a buzzer next to your head to go off, to call you to church for the night office—the first couple of nights I was there I nearly hit the cealing;—there is a similar button next to your bed which you press to confirm you're awake and on the way. The night office lasts about forty minutes or so, then you go back to bed until six, when you have to get up and say your morning prayers privately in your cell before going to church again for the first Mass. After the Masses, it's out to the fields to tend to the crops, since the charterhouse grows all its own food and is self-sufficient. You take a break at noon for lunch and to say your noon day prayers, then back to work until it's time to return to your cell for evening prayers and then to bed.

If it sounds dreary and depressing, it really isn't. Saint Bruno insisted that the charterhouse be a joyful place, and toward that end he insisted that anyone accepted into the community be stable, well-rounded and with a good sense of humor; and, you can see how that would be important in that kind of life. A really intense or overly-sensitive person would probably go bananas in such an environment. The charterhouse is never dark; every room has big windows and skylights and the interior of every room is very bright. It's obviously very austere; there are no statues of any saints, no religious pictures of any kind hanging on the walls; the only religious symbols in the charterhouse that I could see were a crucifix in each monk's private oratory where he says his prayers, and at the door of every cell there is a small statue of the Blessed Virgin before which he says a Hail Mary each time he enters. Even their approach to monastic silence is measured and moderate: while the Trappists take a vow of silence, and developed a complicated system of hand signals to communicate whenever the rule of silence was in effect, the Carthusians don't take a vow of silence; Saint Bruno simply said that the charterhouse should be a quiet place, but if you had to say something, just say and be done with it.

The formation program is long: a two-year postulancy, followed by a two-year novitiate, followed by five years of what is called "Temporary Donation," after which one may be admitted to Perpetual Donation; and, some monks elect to remain as "Donates" the rest of their lives. However, if one is destined for the priesthood (or sometimes even if not), there would follow a second two-year novitiate to prepare for the traditional final vows, which would be required before ordination.  Thus, someone destined for the priesthood could expect to be in the charterhouse for at least twelve years before being ordained. Carthusian priests are what the old Code of Canon Law referred to as "simplex priests," meaning they have no faculties to preach or hear confessions except within the charterhouse itself, and are addressed as "Venerable Father" rather than "Reverend Father." Thus, someone destined for the priesthood could expect to be in the charterhouse for at least twelve years before being ordained. Carthusian priests are what the old Code of Canon Law referred to as "simplex priests," meaning they have no faculties to preach or hear confessions except within the charterhouse itself, and are addressed as "Venerable Father" rather than "Reverend Father."

One of the things I did while I was with them in Vermont was to read the rule of life that Saint Bruno wrote for them in the year 1050, and it's very different from the Rule of Saint Benedict. It's really more like a series of meditations with a few regulations laced in between them, most of them having to do with the virtue of charity. And it struck me that every aspect of that rule is focused on this idea that we are here to please God and no one else. And he goes so far as to suggest that we have to presume this about everyone else, not just ourselves. For example, there’s a passage in the rule which some of you have heard me quote several times, especially during Lent, where he says that if you observe a brother doing something you were told was wrong, whatever it may be—whether it’s conversing with a woman, or entering a shop, or eating something forbidden on a fast day, or taking a nap when he's not supposed to, or doing anything that is ordinarily forbidden by the rule—instead of running to the prior to rat him out, always assume he has permission; and this way, you will never risk sinning against charity.

I never forgot that, and have often speculated how much anxiety we could eliminate from our lives if we could only find a way to live that principle in all our lives. Of course, we have no control over the spiritual lives of others,—except perhaps by example—but we do have control over our own; but, even that can be a hard sell, sometimes. How often have we heard a sermon or read something that strikes a chord in us, and our first thought is to apply it to someone else? How many times have we heard the priest say something about how to behave and the first thing that pops into our heads is, “I sure hope so-and-so heard that”?

This principle of doing the right thing to please God and not caring whether anyone else understands—or even if they misunderstand—is really the principle theme of the Rule of Saint Bruno, and he took it from our Lord's admonitions in Matthew, chapter six, where our Lord says,

…when you fast, do not shew it by gloomy looks, as the hypocrites do. They make their faces unsightly, so that men can see they are fasting; believe me, they have their reward already. But do thou, at thy times of fasting, anoint thy head and wash thy face, so that thy fast may not be known to men, but to thy Father who dwells in secret; and then thy Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward thee (Matthew 6: 16-17 Knox).

What Saint Bruno understood, and what we have to understand as well, is that by fasting our Lord is not simply speaking of abstaining from food for spiritual reasons; fasting here is interpreted as anything that we do that pleases God, even if it is not understood by anyone else. And when we realize that, all of a sudden we see that this has not to do simply with personal acts of mortification, like giving up food, but with everything that touches on our relationship with God and with one another.  A person who consistently does what is right in his daily life will end up disappointing more people than he pleases, if he is truly doing what is right. Sometimes we make the mistake of thinking that what is pleasing to others is what is right, and that’s almost never the case. If it were, life would be a breeze, but we know it isn’t. And if you wanted a “tag line” based on the life and Rule of Saint Bruno to apply to your own life, it would be: “You wouldn't worry so much about what other people think of you if only you realized how seldom they do.” A person who consistently does what is right in his daily life will end up disappointing more people than he pleases, if he is truly doing what is right. Sometimes we make the mistake of thinking that what is pleasing to others is what is right, and that’s almost never the case. If it were, life would be a breeze, but we know it isn’t. And if you wanted a “tag line” based on the life and Rule of Saint Bruno to apply to your own life, it would be: “You wouldn't worry so much about what other people think of you if only you realized how seldom they do.”

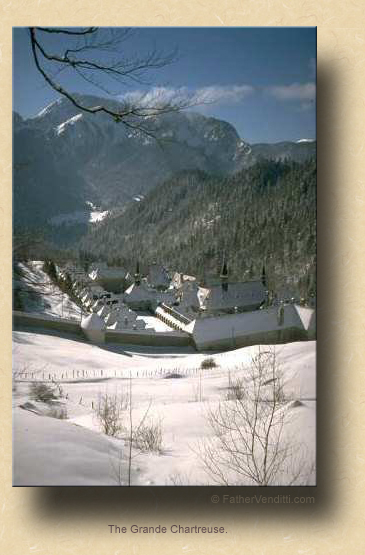

I've said it I don't know how many times this past year, in almost every third homily I've preached here, and I'll say it one more time: our one reason for being on this earth is to work out our salvation; everything else is just window dressing. We have a joke around here whenever we have a weekend when there are no pilgrimage groups or buses coming and no special events: someone will say, “Well, today should be a normal day,” and someone else will add, “Whatever normal is.” Well, whatever normal is, Saint Bruno was it. He never saw visions, he never had a stigmata, he never claimed to have received any special locutions or messages from God or the Blessed Mother, and said that he never wanted to, because he didn't want to believe that God would feel he needed it. He was just a normal guy who wanted to be as perfectly united to our Blessed Lord as he could possibly be, and ended up attracting a lot of other normal people who felt exactly the same way. The Mother House of the Carthusian Order, the Grande Chartreuse high up in the French Alps, is one of the largest monasteries in the Catholic world, and always has been.

So, who should pray to Saint Bruno? Anyone who wants to be united to our Lord, and that should be all of us. Anyone who wants to practice perfect charity, and that also should be all of us. But perhaps just as importantly, anyone who is struggling to be normal in a spiritual environment often beset by hysterical miracle-seekers and would-be visionaries; and, who among us isn't? So, let's pray to Saint Bruno, that we may find our joy not in the approval of others, but in the assurance that, if we follow the Gospel, even if the whole world gets angry and frustrated with us, it doesn't matter, because we have not been put in the world to please it, only to please its maker.

* Born in St. Antoine, Quebec, Marie Durocher (1811-1849) was the youngest of ten children. She spent twelve years assisting one of her younger brothers, a parish priest, during which time she established the first Canadian parish sodality for young women. Later, she founded the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, dying at the age of thirty-eight.

|