Our Lord is Not a Constitutionalist.Galatians 1:11-19;

Luke 7:11-16. The Twentieth Sunday after Pentecost. The Holy & Glorious Apostle Thomas.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

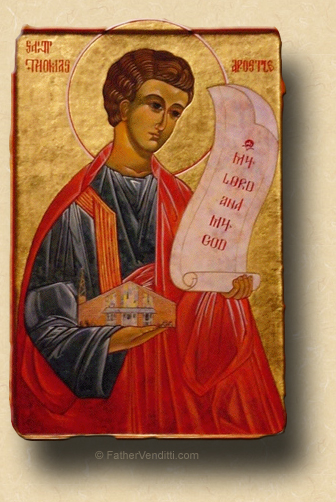

4:48 PM 10/6/2013 — This year, the Twentieth Sunday after Pentecost coincides with the feast of the Blessed Apostle Thomas; not a major feast in our Church, in spite of the fact that he was one of the Twelve, probably because he has an entire Sunday dedicated entirely to him just after Pascha; and, every year we speak rather extensively about that famous incident between Thomas and the risen Lord which is presented to us at the conclusion of Bright Week on Thomas Sunday, and which causes us to sometimes refer to him as “Doubting Thomas.”

Following this familiar event, Thomas disappears from the Gospel; thus, we know nothing for certain about his post-Resurrection activities. Nevertheless, according to ancient traditions, St. Thomas reportedly landed at Kodungalloor in the year of our Lord 52, and founded seven Churches in Southern India in what is now known as the province of Kerala.  His decision to go there is not as extraneous as it sounds, given that Southern India had long before been colonized by the Jews; and, the seven Churches that Thomas established in India correspond to the seven original Jewish colonies there. Some of these groups of Christians continue to exist today. His decision to go there is not as extraneous as it sounds, given that Southern India had long before been colonized by the Jews; and, the seven Churches that Thomas established in India correspond to the seven original Jewish colonies there. Some of these groups of Christians continue to exist today.

The largest group of so-called "St. Thomas Christians," tracing their origins to the Apostle's activities in India, is the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, a Major Archiepiscopal Church in full communion with Rome, which uses the Chaldean or Eastern Syrian liturgical rite. Kerala remains today India's only province with a Catholic majority, and was the only province in India where it was legal for the Church to make converts. Outside Kerala, Christians are subjected to legal—and often violent—persecution. While these persecutions subsided somewhat during the life of Mother Teresa, they returned full force after her death. Today, even Kerala has become the scene of some rather brutal anti-Catholic persecutions; and, while the current Indian government pays lip service to denouncing them, they've done very little to try and prevent them.

A so-called "Gospel of Thomas" surfaced during Gnostic times, but the Church soon rejected it as a forgery; this did not prevent the Gnostics from using its heretical contents to try to disprove the divinity of Christ in the fourth and fifth centuries. Author Dan Brown used elements of this forged "gospel" in his slanderous novel, The Da Vinci Code.

As you know from my homilies over the years on Thomas Sunday, I've always felt a little sorry for the Blessed Apostle Thomas; we remember him primary for doubting our Lord's resurrection, but conveniently forget the fact that, as a missionary, he carried the Gospel farther than any other Apostle, and established vibrant Churches that remain to this day.

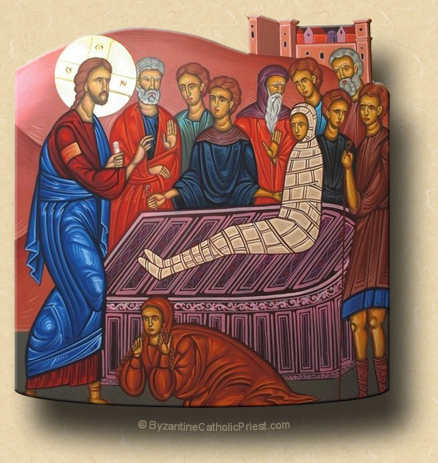

But rather than repeat all of that, I should like instead to focus our attention on today's Gospel lesson, which should be familiar to us since it is chanted during the concluding rites of our Church's funeral Liturgy: the famous incident of our Lord meeting the widow at Naim and raising her son from the dead.

Certainly the most impressive miracles and signs performed by our Lord in the Gospels are those in which he raises someone from the dead: the Synagogue leader’s daughter, the centurion’s manservant, his own relative, Lazarus, and this unknown person of whom we read today, a young man being carried to his grave, accompanied by his grieving mother. It’s a sad scene St. Luke paints for us, which has a happy ending when Christ miraculously restores life to the dead man. It’s a testimony to our Lord’s divinity—for who can raise the dead except God?—as well as his power over death, which he would proclaim most perfectly in his own resurrection.

But the Scriptures speak a metaphorical language that is often foreign to modern ears. For this is more than just a story about Christ’s divinity and his power over death; it is a lesson about sin. All references to death in the Holy Gospel are references to sin. For the Evangelists, sin and death are the same thing: where one is mentioned, the other is understood. Just as physical death envelops the body in darkness, so sin envelops the soul in darkness; which is why St. John describes Christ as “...the light [that] shines in the darkness” (John 1:5). Darkness is the quintessential evil for St. John: sin, error, heresy, disobedience, licentiousness, covetousness, death itself, are all part of the world of darkness in the Holy Gospels. And Christ is that light which shines forth in the darkness and makes it disappear. “Walk as a child of the light,” says our Lord again and again, meaning, “Walk apart from sin.”  Because the person who walks in the way of sin must walk in darkness; he prefers the darkness. It is the darkness that hides his sinful deeds from the eyes of others. Sinful deeds are committed in darkness because they must be secret. When Christ admonishes us to walk as children of the light, he is saying, “Have no need for secrets.” Everything we do, no matter how private, should be able to be seen without scandal. Because the person who walks in the way of sin must walk in darkness; he prefers the darkness. It is the darkness that hides his sinful deeds from the eyes of others. Sinful deeds are committed in darkness because they must be secret. When Christ admonishes us to walk as children of the light, he is saying, “Have no need for secrets.” Everything we do, no matter how private, should be able to be seen without scandal.

Certainly everyone is entitled to privacy; and all of us have private parts of our lives, our jobs, our marriages, which are not intended for public view. Most of the time it’s a question of appropriateness or modesty. But when a person develops a part of his or her life that must be kept secret because it contradicts the life he or she lives in public—because it would cause a scandal for those who know him—such a person must ask himself if it should be at all.

Now, everybody sins. St. John says in his First Epistle that anyone who says he is not a sinner is a liar. I sin, you sin, we all commit sins. But St. John Chrysostom explains to us that, even though we all sin, it is possible to distinguish what he calls the “evil sinner” from the “good sinner”, as odd as that may sound—and I’ve quoted this to you before. The “good sinner”, he says, when he is told he has sinned, reacts with sorrow and begs forgiveness. The “evil sinner”, when his sin is discovered, reacts with indignation, protesting that his privacy has been violated. And over the centuries, no excuse has been used more to defend sinful actions when they are brought to light then the so called right to privacy. The very quintessence of evil in our own society, abortion, was judicially legislated into the law of our country in the Roe vs. Wade decision not because the court said human life was not precious, not because it said abortion was good, but because of what they called the right to privacy. It never occurs to the proponents of this form of murder to ask: If it’s not wrong, why is it so important to protect its privacy? Why must it be done in darkness apart from the knowledge of others if there’s nothing wrong with it?

When Jesus raised the dead man to life as we read in the Gospel lesson, St. Luke added the line, “Then fear came upon them all, and they glorified God...” (Luke 7:16). It sounds like a contradiction, but it isn’t. Fear came upon them because they realized that there is no darkness that can shut out the light of Christ, not even the darkness of death; that the dark rooms that they held in their hearts could be penetrated by Christ. But they glorified God in this because they knew that once a man leaves the darkness and enters into the light—once his sin is exposed and dealt with—then he is free. He is free to walk in the light without shame, no longer having to lurk in the shadows, hiding a part of himself from the eyes of his neighbor, forced by his own choice to live a double life. For then does he realize that whatever pleasure or fulfillment he thought he had in the darkness, it cannot compare to the joy, the rest, the peace given to his soul when there is nothing to hide, when the light can shine brightly on his whole self without cause for shame. No wonder they said of him, “A great prophet has risen among us”; and, “God has visited His people.”

|