An Imperfect Saint and Stories that Don't End Right.

The Memorial of Saint Francis of Assisi.*

Lessons from the primary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Nehemiah 2: 1-8.

• Psalm 137: 1-6.

• Luke 9: 57-62.

…or, from the proper:

• Galatians 6: 14-18.

• Psalm 16: 1-2, 5, 7-8, 11.

• Matthew 11: 25-30.

…or, any lessons from the common of Holy Men & Women for Religious. |

The Third Class Feast of Saint Francis of Assisi, Confessor.

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Galatians 6: 14-18.

• Psalm 36: 30-31.

• Matthew 11: 25-30.

The Seventeenth Wednesday after Pentecost; the Feast of the Holy Martyr Hierotheus, Bishop of Athens; and, the Feast of Our Venerable Father Francis of Assisi.**

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Ephesians 5: 25-33.

• Luke 6: 46—7: 1.

FatherVenditti.com

|

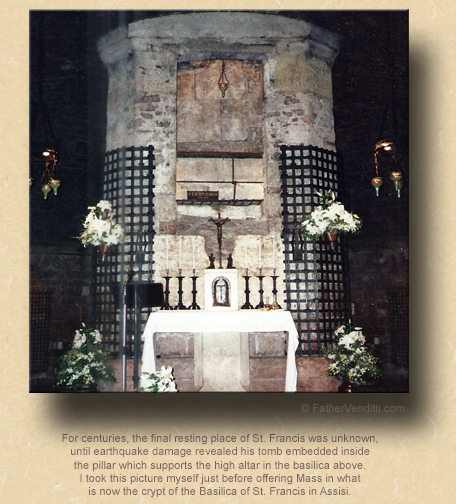

9:16 AM 10/4/2017 — Many years ago I was blessed—or cursed, however you want to regard it—to take a group of college girls on pilgrimage through France and Italy, and one of our stops was Assisi. During our three days there, I stayed in the monastery of the Conventual Franciscans where the Saint’s tomb in located, and offered Holy Mass at the altar of the tomb. Francis, himself, is a very popular saint, as you know, and it can be confusing sometimes to consider all the different religious communities that claim his name. Personally, I recognize only three branches of the Franciscan family: the brown-robed Order of Friars Minor, who believe themselves to be the community founded by Francis; the black-robed Order of Friars Minor Conventual, who actually are the community founded by Francis; and the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, who never claimed to be founded by Francis, inasmuch as they evolved from a reform movement started after his death.*** 9:16 AM 10/4/2017 — Many years ago I was blessed—or cursed, however you want to regard it—to take a group of college girls on pilgrimage through France and Italy, and one of our stops was Assisi. During our three days there, I stayed in the monastery of the Conventual Franciscans where the Saint’s tomb in located, and offered Holy Mass at the altar of the tomb. Francis, himself, is a very popular saint, as you know, and it can be confusing sometimes to consider all the different religious communities that claim his name. Personally, I recognize only three branches of the Franciscan family: the brown-robed Order of Friars Minor, who believe themselves to be the community founded by Francis; the black-robed Order of Friars Minor Conventual, who actually are the community founded by Francis; and the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, who never claimed to be founded by Francis, inasmuch as they evolved from a reform movement started after his death.***

Francis, himself, was an enigma: born of nobility, he completely misunderstood an interior locution he received while praying in front of a crucifix, thinking our Lord wanted him to renovate a crumbling church. Our Lord did, indeed, tell him to “rebuild my Church,” but he meant the whole Church, spiritually from within—which, of course, Francis eventually did. He and his disciples lived a very simple life, but their community was beset by internal struggles from the beginning, resulting in Francis being thrown out of the community he had founded. Part of the problem stemmed from his own misguided humility: he allowed himself to be ordained a deacon so that he could preach in church, but never become a priest; and a religious community that has priests in it must have a priest for its superior.

He is, nevertheless, a very popular saint, due primarily to the simplicity of his life and message, which, unfortunately, has been embellished with so many spurious legends that those things most essential about him are often overlooked.  Francis of Assisi was not a perfect person—no one, not even the saints, are—and it was his own extremism in pursuing a life of poverty and simplicity that resulted in the disintegration of his original community into rival factions. But perhaps that’s the gift he gives us as an intercessor: someone to whom we can pray when things don’t turn out the way we thought they would. Francis of Assisi was not a perfect person—no one, not even the saints, are—and it was his own extremism in pursuing a life of poverty and simplicity that resulted in the disintegration of his original community into rival factions. But perhaps that’s the gift he gives us as an intercessor: someone to whom we can pray when things don’t turn out the way we thought they would.

Today’s Gospel lesson—which is for this Wednesday of Ordinary Time, not for the saint—is a departure from what we’ve been hearing; and, I have to confess that I was more in the mood for another one of our Lord's parables which usually have some simple, down-to-earth lesson in them. There might be such in today's Gospel lesson, but that's not what leaps out from the page. It’s unfortunate that the lesson begins where it does because, in the verses that immediately precede today’s lesson, Saint Luke sets the tone, and the New American Bible actually does a masterful job translating it: “When the days for Jesus' being taken up were fulfilled, he resolutely determined to journey to Jerusalem…” (9: 51 NABRE). Msgr. Knox's translation might even be better, as it clearly transmits the import of the moment: “And now the time was drawing near for his taking away from the earth, and he turned his eyes steadfastly towards the way that led to Jerusalem” (9: 51 Knox).

You understand what Saint Luke is saying to us, I trust: Jesus and His friends are embarking on their last long trip to Jerusalem. He's been there many times, but this will be the last trip because after this is Calvary. And Jesus knows it! What the Apostles knew is pure speculation, but the fact that our Lord knew is actually buried in Luke's cryptic choice of words: He was “resolutely determined” to go, or, as Msgr. Knox so poetically puts it, “…and he turned his eyes steadfastly toward the way that led to Jerusalem.” It's not explicitly said, of course—very few things in Luke's Gospel are—but why else make the remark of how determined our Lord was? The disciples, after all, had tried to dissuade Him from going, suspecting all along what would happen there. So did a lot of other people, who begin, at this point, to start to avoid our Lord for that reason; and, that, too, is alluded to in more of the verses where this lesson should have begun:

And he sent messengers before him, who came into a Samaritan village, to make all in readiness. But the Samaritans refused to receive him, because his journey was in the direction of Jerusalem (vs. 52-53 Knox).

But, even without the knowledge that we have in retrospect—that our Blessed Lord is God and His death on the Cross is preordained and even intended—there is the account of these three individuals who are not put off by what seems to be our Lord's poor decision to walk right into the lion's den, so to speak, but who are, in fact, attracted to the example of sacrifice; and, it's here, in these three men, that we find ourselves in this episode. After all, we wouldn't be here right now if we didn't have some desire to follow our Lord; but, like the three men in the lesson, we're not all at the same stage of readiness.

The first one seems to be the quintessential disciple: he comes right up to our Lord, unsolicited, and says straight out, “I will follow you wherever you go” (v. 57 RM3). We've seen this before, haven't we?  Think back to the Rich Young Man who approaches our Lord (cf. Mark 10: 17-27; &, Matt. 19: 16-22) asking to be part of His company, only the Rich Young Man doesn't know what's ahead, as demonstrated by the fact that he's unwilling to part with his material possessions; but, this man is different: reading Luke between the lines, it seems that, while he may not know the particulars of what awaits our Lord in Jerusalem, he knows it won't be pleasant. Our Lord's mysterious line to him, about foxes having their lairs and birds their nests but the Son of Man having no where to lay His head, is nothing more than our Lord just making sure he understands what he'll be sacrificing. And, as usual, we don't know what he ultimately decides, as often happens in Saint Luke's Gospel: various people cross our Lord's path, He has a brief encounter with them that makes some point or occasions some lesson by our Lord, then they disappear from the narrative, vanishing into thin air, it seems, because, as far as Luke is concerned, the point is made and they've served their purpose. Luke never allows us to get distracted by some human interest story from the spiritual and theological point that's being made. The Rich Young Man, the rabbi who wants to justify himself, the woman at the well in Samaria, the man with the son possessed by demons, the centurion with the dying servant, the one leper who comes back to give thanks for his cure: we never hear from them again; they each have their moment with our Lord, then they're gone. Luke denies us the “closure” of knowing what ultimately happens to them because they are not what all these different passages are about. Like the man in the Gospel lesson for today: Saint Luke cryptically alludes that he at least suspects that, upon arriving in Jerusalem, our Lord will be involved in some difficultly of some sort, and he wants to follow anyway. Our Lord's response, highlighting the nature and mystery of the Cross for anyone who chooses to follow the way of Jesus, is more for our benefit than for this man's; and, the Evangelist doesn't bother to tell us what this man decides or what he does because it isn't important. The Gospel is not a novel: it isn't important that all the sub-plots are resolved and all the characters are accounted for. Think back to the Rich Young Man who approaches our Lord (cf. Mark 10: 17-27; &, Matt. 19: 16-22) asking to be part of His company, only the Rich Young Man doesn't know what's ahead, as demonstrated by the fact that he's unwilling to part with his material possessions; but, this man is different: reading Luke between the lines, it seems that, while he may not know the particulars of what awaits our Lord in Jerusalem, he knows it won't be pleasant. Our Lord's mysterious line to him, about foxes having their lairs and birds their nests but the Son of Man having no where to lay His head, is nothing more than our Lord just making sure he understands what he'll be sacrificing. And, as usual, we don't know what he ultimately decides, as often happens in Saint Luke's Gospel: various people cross our Lord's path, He has a brief encounter with them that makes some point or occasions some lesson by our Lord, then they disappear from the narrative, vanishing into thin air, it seems, because, as far as Luke is concerned, the point is made and they've served their purpose. Luke never allows us to get distracted by some human interest story from the spiritual and theological point that's being made. The Rich Young Man, the rabbi who wants to justify himself, the woman at the well in Samaria, the man with the son possessed by demons, the centurion with the dying servant, the one leper who comes back to give thanks for his cure: we never hear from them again; they each have their moment with our Lord, then they're gone. Luke denies us the “closure” of knowing what ultimately happens to them because they are not what all these different passages are about. Like the man in the Gospel lesson for today: Saint Luke cryptically alludes that he at least suspects that, upon arriving in Jerusalem, our Lord will be involved in some difficultly of some sort, and he wants to follow anyway. Our Lord's response, highlighting the nature and mystery of the Cross for anyone who chooses to follow the way of Jesus, is more for our benefit than for this man's; and, the Evangelist doesn't bother to tell us what this man decides or what he does because it isn't important. The Gospel is not a novel: it isn't important that all the sub-plots are resolved and all the characters are accounted for.

That being said, today's lesson does not end without two more mysterious encounters, two more nameless people our Lord just happens to bump into before they, too, vanish into thin air; but, they are very different from the first fellow. They seem to be anxious to walk along with our Lord as well, but not without conditions; and, the conditions they have seem to us perfectly reasonable: one wants nothing more than to go home and say goodbye first to his family; the other one has a dead father lying at home. We want to ask our Lord what He actually wants here. Does he really want this man to leave his father decomposing on his death bed while he obeys the Lord's command to proclaim the kingdom of God? But notice that Luke, again, doesn't tell us what either of them decides to do.  Our Lord says what he says to each of them, and—poof—they're gone. What they do doesn't matter; it's what we do that matters. And it's to that end that our Lord speaks to us the last line of today's Gospel lesson: “No one who sets a hand to the plow and looks to what was left behind is fit for the kingdom of God” (v. 62 RM3). Our Lord says what he says to each of them, and—poof—they're gone. What they do doesn't matter; it's what we do that matters. And it's to that end that our Lord speaks to us the last line of today's Gospel lesson: “No one who sets a hand to the plow and looks to what was left behind is fit for the kingdom of God” (v. 62 RM3).

Each of us could tell the story of our own encounters with our Blessed Lord. And each of us is often tempted to view that story like it was a novel or a television drama, with all the characters accounted for and all the plot lines neatly tied up and resolved. The problem is that the interior life doesn't work that way: the disease of sentimentality, the constant looking backward into the fog of regret: what might have been, what could have been, what should have been. None of it matters. The woman who comes into confession full of regret that she may have treated her husband uncharitably in the last difficult days of his life, or the parent full of regret that the falling away of his children from the faith might have been avoided had he done something different or said something different. An elderly priest, now deceased, once came to me, full of remorse over something he had done some thirty or forty years before, which would have caused a great scandal to the Church had it ever been known; and, I asked him if he had confessed it before, and he said, “Oh, yes, many years ago.” So I asked him if it was likely that it would ever become known, and he said, “Oh, no, Father, everyone involved has been dead for some time.” And I said to him, “Then get back to your parish and get on with it!” What do you expect from our Lord? Closure? Our Lord is not Doctor Phil. He does not offer us closure. He offers us absolution. He offers us Grace. Whatever else we think we need we obtain through cultivating the virtues of Faith and Hope.

Let’s ask our blessed Lord, though the intercession of Saint Francis, to grant us those most necessary graces.

* A small note on titles given to saints in the Roman Missal: The question has been asked as to why the Memorial of St. Francis carries no title for the saint as most others do, such as "Martyr" or "Religious" or "Bishop" or whatever title would apply which refers to the appropriate common. In the missal of St. Pius V—and subsequently in that of St. John XXIII—male saints who were neither martyrs nor bishops were identified by the title “Confessor” (it has nothing to do with hearing confessions) and, in both missals the title is applied quite liberally, even landing on such saints as St. Joseph, the Husband of Mary, as well as on any number of male saints, priests or not, who would otherwise enjoy no other title; and, there is, in fact, a specific common in both missals for “a Confessor not a Bishop,” which could be used for either a priest or a layman. In the Missal of Bl. Paul VI, the title “Confessor” is suppressed and replaced by “Priest,” which refers to the common of Pastors, which causes a problem for St. Francis who was ordained a deacon but not a priest. There are, of course, any number of titles used elsewhere in the Missal of Bl. Paul VI which could be applied to Francis, such as “Deacon” or “Religious,” both of which would be accurate, and specific reference is made to the common of Holy Men and Women for Religious for a selection of optional lessons which can be read on his day; but, for some reason, that missal does not apply even the title "Religious" to his name. Thus, he is one of the few saints in the Missal of Bl. Paul VI whose name stands alone with no title. Personally, I should like to see Francis declared a Doctor of the Church, a designation which makes no reference to whether the saint so identified was ever ordained, and for which there is a common. Thus, his title would then be “Francis of Assisi, Deacon and Doctor of the Church,” and the chants, prayers and lessons from the common of Doctors would be additionally available. Whether the erudition and importance of St. Francis’ life and teaching to the development of the Universal Church rises to the level which would justify such a declaration is not for me to say; but, if Teresa of Avila and the deacon Ephrem the Syrian can be Doctors of the Church, why not Francis?

Additional note: While the Ruthenian typicon refers to this saint as "Our Venerable Father Francis," their use of the word "father" often has nothing to do with the priesthood, especially when preceded by the adjective "venerable."

** According to the menaion of the Greek Church, Hierotheus was one of the nine counsellors of the Areopage, was converted by the Apostle Paul who consecrated him Bishop of Athens, and was present with the Apostles at the Dormition of the Mother of God.

*** I tread lightly here inasmuch as the three main branches of the Franciscan family can become testy regarding this topic. The brutal, historical reality is that Francis’ original community, the first of the modern “mendicant” orders (literally, “monks without abbeys” or “begging orders”), known as the Order of Friars Minor, saw the need to build a stable monastery in Assisi, and Francis resisted the ownership of property. It was this that resulted in his expulsion from the community he founded. His loyalists thus formed what is known today as the Order of Friars Minor, with his original community adding the word “Conventual” to their name, taken from the word “convent,” because they had built one against Francis’ orders. The Conventuals wore a habit similar to Francis’ original habit (preserved at the monastery in Assisi), which was gray (Francis never wore brown), but it eventually evolved into black, while the new OFMs eventually developed a brown habit.

Following Francis’ death, a few members of both communities, fed up with all the bickering, decided to form a third group which they named the Capuchins, embracing an extreme regard for Holy Poverty and detachment from the world. While initially a completely contemplative community, it eventually branched out into apostolic work. They wore a brown habit, but along the same design as Francis’ original gray habit.

In Assisi today, these three main branches of the Franciscan family have divided the various sites connected with the Saint’s life between them; of these, the Capuchins have all the best sites, including the church of San Damiano, where Francis received his first locution, as well the mountain retreat where he spent his last days and received the Stigmata.

When the late Fr. Benedict Groeschel, OFM, Cap. (my former professor in Ascetical Theology and spiritual director), broke away from the Capuchins to form the Capuchin Franciscans of the Renewal (CFR) in New York, he retained the original Capuchin habit but made it gray; thus, of all the many and varied groups that claim to be Franciscan, the CFRs wear a habit most closely resembling what Francis wore. To his dying day, Fr. Benedict was continually quoting to me things I had said in papers I had written or said in class in seminary thirty-five years ago that I couldn’t possibly remember. While his new community works among the poorest of the poor in mostly urban areas, his theological foundation for the establishment was to promote what was commonly referred to as “the reform of the reform,” referring to the need to re-evaluate and properly implement the reforms following the Second Vatican Council, hijacked by Cardinal Bugnini and the Bologna Institute, challenged contentiously and directly by Pope St. John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI. Inasmuch as Pope Francis has repudiated his predecessors, condemning and forbidding any further discussion of a “reform of the reform,” it’s unclear what the future of the CFRs may be.

|