Here, O God, Is My Sacrifice, a Broken Spirit.

The Thirtieth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the primary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Exodous 22: 20-26.

• Psalm 18: 2-4, 47, 51.

• I Thessalonians 1: 5-10.

• Matthew 22: 34-40.

The First Class Feast of the Kingship of Our Lord Jesus Christ.*

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Colossians 1: 12-20.

• Psalm 71: 8, 11.

• John 18: 33-37.

The Twenty-First Sunday after Pentecost (the Sixth after the Holy Cross); the Feast of the Holy Venerable Martyr Anastasia; the Feast of Our Venerable Father Abraham the Hermit; and, the Remembrance of the Passing of Our Venerable Father Abraham of Rostov, Archimandrite & Wonder-Worker.**

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Galatians 2: 16-20.

• Luke 8: 26-39.***

FatherVenditti.com

|

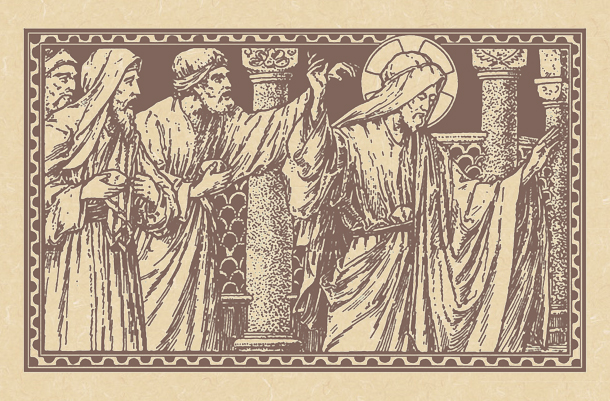

7:52 AM 10/29/2017 — Today’s Gospel lesson begins with a circumstance which may seem strange to us: the Pharisees feeling a little bit of encouragement over the fact that our Lord had sparred with the Sadducees over the question of the resurrection of the dead, and pretty much made mincemeat of them in the debate, the incident occurring in your Bible just before today’s lesson. A long time ago I had explained how there were two distinct classes of rabbis in our Lord's time: the traditionalist wing of the rabbinical class called the Sadducees, and a more progressive group which is first evidenced in the Books of Maccabees, just sixty years or so before the time of our Lord, called the Pharisees. 7:52 AM 10/29/2017 — Today’s Gospel lesson begins with a circumstance which may seem strange to us: the Pharisees feeling a little bit of encouragement over the fact that our Lord had sparred with the Sadducees over the question of the resurrection of the dead, and pretty much made mincemeat of them in the debate, the incident occurring in your Bible just before today’s lesson. A long time ago I had explained how there were two distinct classes of rabbis in our Lord's time: the traditionalist wing of the rabbinical class called the Sadducees, and a more progressive group which is first evidenced in the Books of Maccabees, just sixty years or so before the time of our Lord, called the Pharisees.

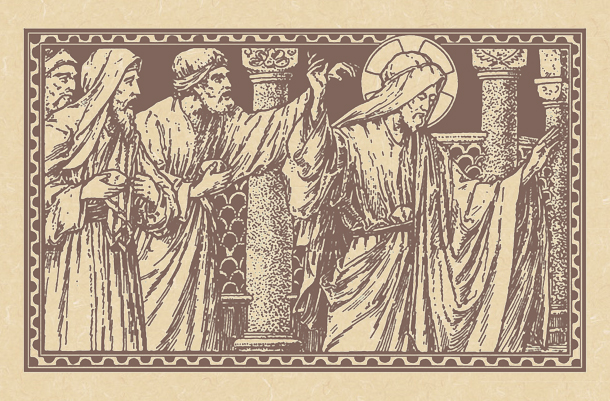

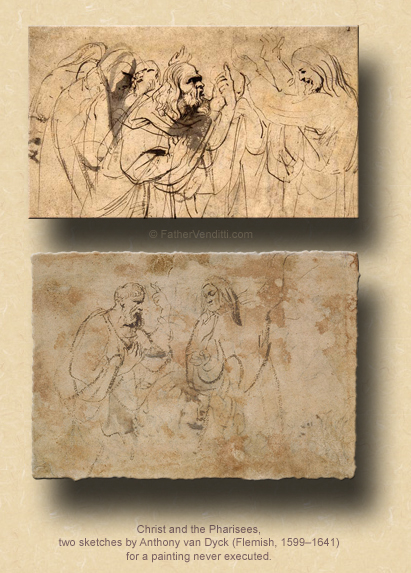

The Pharisees were radical in a number of ways, but two elements of their theology stand out: they preached a resurrection from the dead, which the Sadducees rejected; but, more to the point, they instituted the synagogue service which enabled the Jewish people to gather for prayer on the Sabbath without making the journey to the Temple in Jerusalem. But synagogue worship was very different from temple worship. The service in the temple was a sacrifice: an animal, usually a lamb, was slaughtered and burned on the altar. The synagogue service was not a sacrifice: it consisted of reading from, then commenting on, the Holy Scriptures; and, this really angered the Sadducees. The Sadducees viewed the synagogue service in much the same way that you and I would view a Protestant service: they read from and talk about the Bible, but there's no sacrifice, so it's not real in a sacramental sense. That's exactly how the Sadducees viewed the synagogue.

We often like to view the Pharisees as our Lord's primary nemesis, because they're always challenging Him about things He's said or things He's done; but, in reality, He and His disciples all came out of the Pharisaical tradition. Jesus preached a resurrection from the dead—although the resurrection He preached was to be His own—and He and His disciples all worshiped in the synagogue every single Sabbath; and, sometimes I don't wonder that the reason the Holy Gospels show our Lord clashing with the Pharisees so much more frequently than with the Sadducees is because the Pharisees know that our Lord is basically on their side, and don't understand why He continues to do things of which they don't approve, whereas the Sadducees would consider our Lord a lost cause and not worth engaging.

The synagogue service itself was very orderly and regimented. It began with the Shema prayer from Deuteronomy 6: 4: שְׁמַע, יִשְׂרָאֵל: יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ, יְהוָה אֶחָד. (Sh'ma Yis'ra'eil! Adonai Eloheinu. Adonai echad): “Hear, O Israel! The Lord is God. The Lord is One.” And the Shema prayer is, in fact, the first of the two Great Commandments referenced by our Lord today. It's what a devout Jew will tack on the door-post of his home. The second commandment is found in the Book of Leviticus: “Do not seek revenge, or bear a grudge for wrong done to thee by thy fellow-citizens; thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself; thy Lord is his” (19: 18 Knox). What is new in the teaching of Jesus is the fact the He puts these two commandments together and puts them in a certain order. This one is first, and the other is second. That's the point that Jesus is making. And when you think about it, you can see how important a point that is for us in our time.

There are too many today who seek to assuage a guilty conscience by having recourse to the Corporal Works of Mercy. That's not to say that they aren't important, or that they don't cancel a multitude of sins, because they do; and, we know our Holy Father has been encouraging us to rededicate ourselves to the care of the poor and the needy.  I'm not contradicting him, but only pointing out the danger: the danger of reinventing the Gospel of Jesus Christ, seeing it as nothing more than a blueprint for social justice, and Christian living as simply a matter of feeding the hungry and sheltering the homeless, having little, if anything, to do with how we live our private lives. This is rooted in the inability of modern man to acknowledge a truth outside of himself, which results in him professing a religion of which he knows little, making it up for himself as he goes along. Christians who think this way are really the Sadducees of our time, who, like their counterparts of the first century, think that they have it all figured out. And it takes the Divine wisdom of our Lord to put it all back in perspective so simply: yes, we must do good for others;— that is a part of the Gospel message—but, we must do it for the right reason. It is not our good works themselves that please God, but the fact that they are done for Him, in conjunction with an otherwise holy life; just as the Psalmist says, "…here, O God, is my sacrifice, a broken spirit; a heart that is humbled and contrite thou, O God, wilt never disdain" (51: 19 Knox). I'm not contradicting him, but only pointing out the danger: the danger of reinventing the Gospel of Jesus Christ, seeing it as nothing more than a blueprint for social justice, and Christian living as simply a matter of feeding the hungry and sheltering the homeless, having little, if anything, to do with how we live our private lives. This is rooted in the inability of modern man to acknowledge a truth outside of himself, which results in him professing a religion of which he knows little, making it up for himself as he goes along. Christians who think this way are really the Sadducees of our time, who, like their counterparts of the first century, think that they have it all figured out. And it takes the Divine wisdom of our Lord to put it all back in perspective so simply: yes, we must do good for others;— that is a part of the Gospel message—but, we must do it for the right reason. It is not our good works themselves that please God, but the fact that they are done for Him, in conjunction with an otherwise holy life; just as the Psalmist says, "…here, O God, is my sacrifice, a broken spirit; a heart that is humbled and contrite thou, O God, wilt never disdain" (51: 19 Knox).

Practically speaking, we have to look at our own lives. How many of us think that we are all right before God because of all the wonderful things we've done for our fellow man or even for the Church, when the real question should be: "When was the last time I went to confession? When did I last really prepare myself for Holy Communion? When was the last time I spoke with our Lord, not because I wanted or needed something, but simply because I wanted to be with Him? When did I do something for God that wasn't rooted in the social gospel but rather in the moral gospel, the Gospel of the Spirit, the Gospel of prayer and penance, the Gospel of the Cross?" God want's our good works only if they bring us closer to Him and motivate us to live holy lives, and living a holy life isn't so much a matter of "doing" but of "being."

As we offer up together the Sacrifice of the Lord's Body and Blood, let us remember that, if we can't offer ourselves, then we have nothing of value to offer.

* In the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, Christ the King is always observed on the last Sunday of October, completely displacing whatever Sunday after Pentecost would occur, with the remaining Sunday's after Pentecost resuming thereafter. In the ordinary form, Christ the King is the last Sunday of Ordinary Time, this year on November 26th, the following Sunday being the first of Advent.

** Following the feast and postfestive period of the Holy Cross (Sept. 14th through 21st), the Greek Church actually labels these Sundays as “Sundays after the Holy Cross” and begins to number them accordingly, calling today "The Sixth Sunday after the Holy Cross," while the Ruthenian and Russian Churches continue to number them as "Sundays after Pentecost" (though in some older Ruthenian typicons the Greek custom is observed). The historical context of this custom was the Greek practice of marking the birthday of the Emperor Augustus on September 23rd, which they regarded as the first day of the Church year. It was not until the fall of the empire that the new year observance was moved to Sept. 1st throughout the Churches of the Byzantine Rite.

Anastasia, sometimes called "the Roman," was a widow who consecrated her life to helping the poor and sick; she was martyred toward the end of the third century. Some Eastern Churches commemorate her on December 22nd.

Abraham, called "the Hermit," is believed to have lived in Lampsacus, Mysia, in the sixth century. Married against his will, he left his wife and dwelled in the wilderness as a hermit.

Abraham of Rostov was born in the tenth century to a non-Christian family in Galich, Russia. After a near-death experience and healing, he converted to Christianity and became a monk. He preached the Gospel in his native region, and founded the monastery of the Theophany in Rostov, as well two parish churches.

*** The four Gospels are all read in their entirety in the Byzantine Churches, and the reading of each begins with a great feast. The Gospel of St. John begins with the Feast of Feasts, Pascha, and is read until Pentecost. The Gospel of St. Matthew begins with Pentecost, and is read until the Feast of the Holy Cross, after which the Gospel of St. Luke is read all the way through until the Great Fast; but, because the Divine Liturgy is offered only on Saturday and Sunday in the Great Fast, the left-over passages are read in the last six weeks of the Matthean and Lucan cycles. This is why the Byzantine Churches begin the reading of Luke’s Gospel on the Sunday after the Holy Cross no matter where they are in the cycle of "Sundays after Pentecost." The Epistles, on the other hand, are read continuously without any adjustment, creating a discrepancy between Epistle and Gospel. This year, there is a discrepancy of two weeks until Dec. 28th. In the Byzantine Churches, this is commonly called "the Lucan Jump." Thus, today, the Epistle sung is the one for the Twenty-First Sunday, and the Gospel the one ordinary sung on the Twenty-Third Sunday.

|