Coin-Collecting with Our Lord.

The Twenty-Ninth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the primary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 45: 1, 4-6.

• Psalm 96: 1, 3-5, 7-10.

• I Thessalonians 1: 1-5.

• Matthew 22: 15-21.

The Twentieth Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ephesians 5: 15-21.

• Psalm 144: 15-16.

• John 4: 46-53.

The Twentieth Sunday after Pentecost (the Fifth after the Holy Cross); the Feast of the Holy Bishop Abercius, Equal to the Apostles & Wonderworker; the Feast of the Seven Holy Children of Ephesus; and, the Feast of Our Holy Father John Paul II, Pope of Rome.*

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Galatians 1: 11-19.

• Luke 16: 19-31.**

FatherVenditti.com

|

7:26 AM 10/22/2017 — You can’t turn the TV on anymore without seeing something peculiar going on in the political life of our country. It’s always been so, it’s just that it seems more pronounced nowadays because of the media’s desire to sensationalize everything. Journalism, after all, isn’t a public service, it’s a business; and, if whatever news program we’re watching can succeed is getting us all hot and bothered about something, then we’ll watch more of it and see more commercials. 7:26 AM 10/22/2017 — You can’t turn the TV on anymore without seeing something peculiar going on in the political life of our country. It’s always been so, it’s just that it seems more pronounced nowadays because of the media’s desire to sensationalize everything. Journalism, after all, isn’t a public service, it’s a business; and, if whatever news program we’re watching can succeed is getting us all hot and bothered about something, then we’ll watch more of it and see more commercials.

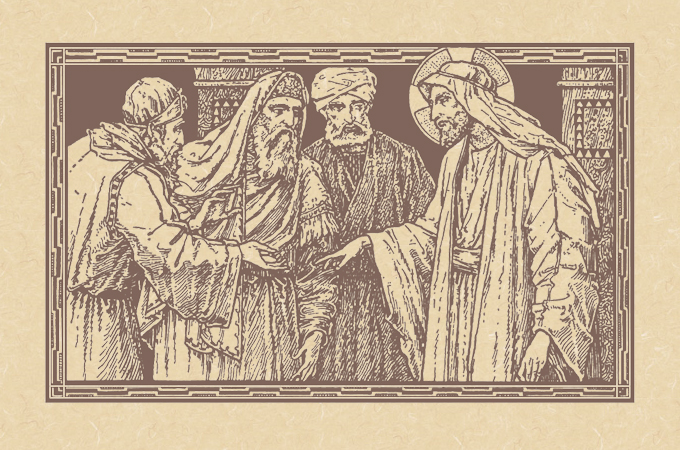

So, it can be somewhat consoling to see our Blessed Lord, Himself, walking a moral tight-rope between religion and politics in his dispute with the Pharisees and Herodians, and in so doing giving us a valuable lesson on how the religiously minded person should relate to his civic duties and his relationship to the state. But in interpreting our Lord’s words and actions in today’s Gospel lesson, it’s important that we view them within the context of the whole picture being presented to us by the lesson from Isaiah with which this episode is paired; and, understanding what the Prophet is talking about requires us to know a little history.

In 597 BC, Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon, took Jerusalem in response to a rebellion on the part of the Jews. The treasures of the Temple of Solomon were plundered, and the Jewish people—some of them—were dispersed through his empire. The Jews revolted again in 587, just ten years later, and this time Nebuchadnezzar was more severe: he laid siege to Jerusalem for eighteen months, destroyed the Temple, and deported almost all the Jews with only a handful of the poorer classes left in what was left of the city. Many if not most of the Psalms were written during this period, and sing of the longing of the people to return home. But the Babylonian empire was invaded and conquered by the Persians in 539, and the following year King Cyrus issued a decree allowing the Jews to return home and rebuild their Temple, which is what the Books of Ezra and Nehemiah are all about. And in today’s first lesson from Isaiah, the Prophet is reminding his people that Cyrus was a pagan king who had been raised up and used by God for a good purpose, the moral of the story being that there isn’t anything that’s outside of God’s domain; He can choose the instruments of our salvation and spiritual perfection from wherever He chooses.

If you think about it, it’s kind of self-evident. How many of us can think back to someone we once knew who was not a Catholic or a Christian or even a believer in God who had a positive influence on us, and who changed us for the better? Not to get too personal, but during a very difficult time in my early priesthood, while working in the hospital, I was befriended by an Orthodox rabbi who gave me a great deal of hope, and without whom I can’t say what would have happened to me. How good is God, then, that He can use anyone or anything He pleases to help us along the way? Just as God raised up a pagan King to free Israel and allow them to return home, so He can do the same for us when need be.

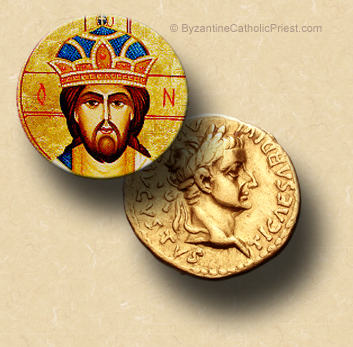

And that is the context in which the Church asks us to consider our Lord’s words to us today. The question presented to Him is a malicious one: the Pharisees are trying to trap our Lord. Rome, after all, is the enemy, a pagan government occupying Jerusalem, and they are trying to trap our Lord into saying something that they can use to brand Him as a heretic and discredit Him.  Specifically, they ask Him whether it’s lawful to pay the Roman tax with the idea that paying the tax constitutes contributing to a pagan ruler. Our Lord’s response is, of course, masterful, as He asks to see the coin of the realm, and asks them in return whose image and name it bears, giving us words we all know: “…give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s” (Matt. 22: 21 Knox); and, in so doing He lays the blueprint for how the Christian should relate to civil authority, and this becomes the basis for the Catholic Church’s teaching that all authority, even civil authority, comes from God and must be respected to the extent that it does the will of God. Specifically, they ask Him whether it’s lawful to pay the Roman tax with the idea that paying the tax constitutes contributing to a pagan ruler. Our Lord’s response is, of course, masterful, as He asks to see the coin of the realm, and asks them in return whose image and name it bears, giving us words we all know: “…give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s” (Matt. 22: 21 Knox); and, in so doing He lays the blueprint for how the Christian should relate to civil authority, and this becomes the basis for the Catholic Church’s teaching that all authority, even civil authority, comes from God and must be respected to the extent that it does the will of God.

Of course, we know that civil authority doesn’t always do the will of God, which is why we must be thankful that we live in a country where we have a voice in how we are governed, as it is our Christian duty to use that voice to promote the ends of God—to safeguard human life from the moment of conception, to defend the family, to protect religious liberty and the rights of parents regarding the education of their children. As the Lord speaks through the Prophet Isaiah: “Woe to those who decree iniquitous decrees” (10: 1 RSV).

But all of this is obvious, I think. What isn’t always so obvious is how difficult it is to maintain our spiritual equilibrium in what seems to be such a politically charged environment. And here is where I will repeat something I said on a Saturday a couple of week’s ago. It's very easy to watch the news and become upset or depressed or angry or all of the above, and to think that the world is simply coming apart at the seams; but is it really? I actually had a conversation not long ago with someone who was complaining about how upset he was about everything that he was seeing in the news, and I don’t think he was expecting the advice I gave him, because my advice to him was to switch it off. It’s like that old joke where the man goes in to see his doctor and he says, “Doctor, it hurts when I do this.” And the doctor replies, “Then, don’t do that.” If watching the news upsets us, why is the advice to simply turn it off not acceptable to us? Because we’re afraid that if we do, we’re going to miss something; or, maybe its because we've convinced ourselves that, if we don't keep ourselves informed, that means we're apathetic and don't care. As I said at the beginning, journalism is not a public service; it’s a business. It makes its money by selling advertising, but advertising doesn’t make any money unless a lot of people are watching. So, the talking head spouting news at us has a commercial interest in doing everything he can to make sure our eyes and ears are glued on him and his channel as often and as long as possible.  So, no matter what is actually happening in the world—or not happening as the case may be—he’s got to find a way to make sure we think the world is falling apart, and we’d better darn well watch every minute or we’re gonna miss it. If he’s got footage of some explosion or mass murder, he’ll play it for us over and over again, each time embellishing it with even more intense descriptions of the carnage; then he’ll truck out the ubiquitous panel of experts and analysts and retired generals who will each tell us how this is, indeed, the most important and critical thing that has ever happened in the history of the universe. If there are victims, they will be paraded before us so that we can share in their pain and moved by their suffering. If there's some sort of standoff with some gunman, or there's a manhunt going on, if we so much as leave to go to the kitchen and get a Coke, we’ll be sorry because we’ll miss the end of the world. Maintaining our spiritual equilibrium and tending to our interior life is difficult enough in today's hectic world; allowing ourselves to become saturated with information overload in the form of this kind of mercenary propaganda makes it practically impossible. So, no matter what is actually happening in the world—or not happening as the case may be—he’s got to find a way to make sure we think the world is falling apart, and we’d better darn well watch every minute or we’re gonna miss it. If he’s got footage of some explosion or mass murder, he’ll play it for us over and over again, each time embellishing it with even more intense descriptions of the carnage; then he’ll truck out the ubiquitous panel of experts and analysts and retired generals who will each tell us how this is, indeed, the most important and critical thing that has ever happened in the history of the universe. If there are victims, they will be paraded before us so that we can share in their pain and moved by their suffering. If there's some sort of standoff with some gunman, or there's a manhunt going on, if we so much as leave to go to the kitchen and get a Coke, we’ll be sorry because we’ll miss the end of the world. Maintaining our spiritual equilibrium and tending to our interior life is difficult enough in today's hectic world; allowing ourselves to become saturated with information overload in the form of this kind of mercenary propaganda makes it practically impossible.

My point is simply this: world events are not unfolding any faster than they have in the past, there are no more frequent tragedies than there were in the past, and the world is not falling apart at the seams. If it seems that way, that’s because the events of the day are being packaged and repackaged in an ever increasing sensationalistic way for the purpose of doing exactly what they're doing: causing us to park our rear ends in front of the TV, getting us all hot and bothered over events about which we can do nothing … nothing, or course, except pray, which we should be doing every day anyway. So, the advice of the doctor in the joke is actually quite sound: “Doctor, it hurts when I do this.” “Then, don’t do that.”

“Father, I get upset when I watch the news.” “Then, don’t watch the news.” I can guarantee that, if the world comes to an end, you’re not going to miss it because you weren’t watching the news. Every day we ask the Mother of God to “turn Thine eyes of mercy towards us” as we suffer in this “valley of tears”; and, what is it we ask Her to do whenever we pray the Hail, Holy Queen? We ask Her to “show unto us the Blessed Fruit of Thy womb, Jesus.” We shall see Him in just a few moments in the Most Blessed Sacrament of the Altar; and, there, right before us, we will have the answer to everything going on in the world that upsets us.

Yes, return to Caesar what belongs to Caesar, but that can’t get in the way of giving to God what has always been His from the beginning of time.

* Today is called "The Fifth Sunday after the Holy Cross" because "The Sunday after the Exaltation" (Sept. 17th) is considered part of the Postfestive period of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, and thus part of the feast itself. Following the feast and postfestive period of the Holy Cross (Sept. 14th through 21st), the Greek Church actually labels these Sundays as “Sundays after the Holy Cross” and begins to number them accordingly, calling today "The Fifth Sunday after the Holy Cross," while the Ruthenian and Russian Churches continue to number them as "Sundays after Pentecost" (though in some older Ruthenian typicons the Greek custom is observed). The historical context of this custom was the Greek practice of marking the birthday of the Emperor Augustus on September 23rd, which they regarded as the first day of the Church year. It was not until the fall of the empire that the new year observance was moved to Sept. 1st throughout the Churches of the Byzantine Rite.

Abercius was Bishop of Hiropolis in Phrygia at the time of Emperor Marcus Antonius (161-180). He died toward the end of the second century. In the custom of many early Christians, he inscribed his own tombstone, which gives an account of his life, travels and faith, thanking Christ for the gift of his faith, expressing his love for the Mother of God, and exhorting all who see it to pray for him. It is now in the Lateran Museum.

The Seven Holy Children, all blood brothers, were sealed alive in a cave as punishment for their faith by the Emperor Decius c. 250. An ancient legend claims that, after three hundred years, they came out alive; however, note that this same story is told in the Quran regarding three Muslim brothers.

** The four Gospels are all read in their entirety in the Byzantine Churches, and the reading of each begins with a great feast. The Gospel of St. John begins with the Feast of Feasts, Pascha, and is read until Pentecost. The Gospel of St. Matthew begins with Pentecost, and is read until the Feast of the Holy Cross, after which the Gospel of St. Luke is read all the way through until the Great Fast; but, because the Divine Liturgy is offered only on Saturday and Sunday in the Great Fast, the left-over passages are read in the last six weeks of the Matthean and Lucan cycles. This is why the Byzantine Churches begin the reading of Luke’s Gospel on the Sunday after the Holy Cross no matter where they are in the cycle of "Sundays after Pentecost." The Epistles, on the other hand, are read continuously without any adjustment, creating a discrepancy between Epistle and Gospel. This year, there is a discrepancy of two weeks. In the Byzantine Churches, this is commonly called "the Lucan Jump." Thus, today, the Epistle sung is the one for the Twentieth Sunday, and the Gospel the one ordinary sung on the Twenty-Second Sunday.

|