Would You Like Some Figs with Your Whine?

The Twenty-Ninth Saturday of Ordinary Time; the Memorial of Saint John Paul II, Pope; or, the Memorial of the Blessed Virgin Mary on Saturday.

Lessons from the secondary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ephesians 4: 7-16.

• Psalm 122: 1-5.

• Luke 13: 1-9.

|

For the memorial of the Pope, lessons from the feria as above, or any lessons from the Common of Pastors for a Pope.*

|

|

For the memorial of the Mother of God, lessons from the feria as above, or any lessons from the Common of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

|

The Fourth Class Feria of the Blessed Virgin Mary on Saturday.

First lesson from the common "Salve, sancta Parens…" of the Blessed Virgin Mary "After Trinity Sunday until Advent," the rest from the primary of the same common, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ecclesiasticus 24: 23-31.**

• [Gradual] Benedicta et venerábilis es…***

• Luke 11: 27-28.

The Twenty-Second Saturday after Pentecost; the Feast of the Holy Bishop Abercius, Equal to the Apostles & Wonderworker; the Feast of the Seven Holy Children of Ephesus; and, the Feast of Our Holy Father John Paul II, Pope of Rome.†

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• II Corinthians 8: 1-5.

• Luke 7: 1-10.

FatherVenditti.com

|

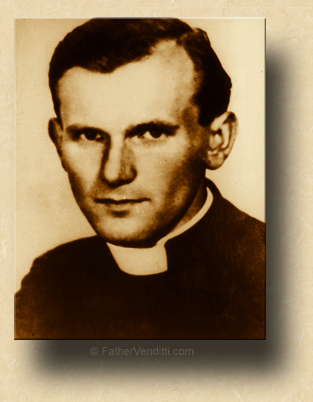

9:50 AM 10/22/2016 — We celebrate today the Memorial of Pope Saint John Paul II. Canonized by Pope Francis on April 27th a couple of years ago, there is no Mass for him in the Missal, so the Mass is taken from the Common of Pastors for a Pope. 9:50 AM 10/22/2016 — We celebrate today the Memorial of Pope Saint John Paul II. Canonized by Pope Francis on April 27th a couple of years ago, there is no Mass for him in the Missal, so the Mass is taken from the Common of Pastors for a Pope.

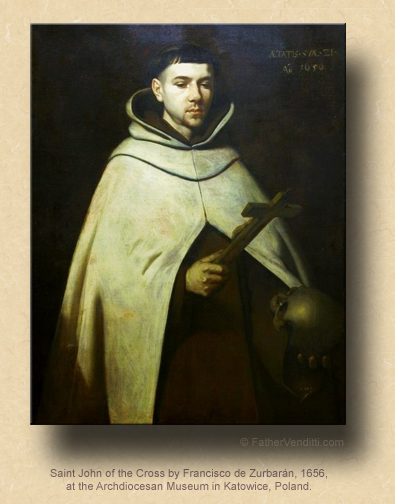

Born in 1920 in Wadowice, Poland, Karol Józef Wojtyla lost his mother at a young age, was raised by his father, and fell under the influence of a group of Catholic young people who, under the guidance of a very learned and pious layman, based their spiritual life on the works of the Spanish Mystics John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila—whom you may remember from the latter's memorial some days ago, were considered suspect in traditional circles because their ethereal mysticism deviated from the more cerebral method of meditation preached by Saint Ignatius and the Jesuit retreat masters (the Jesuits succeeded in keeping their works banned from the seminaries for over a century). He went on to study for the secular priesthood in an underground seminary operated by Prince Adam Stefan Cardinal Sapieha, the last of Poland's bishops to come from the nobility, and was ordained for the Archdiocese of Krakow. He studied and taught philosophy at the university level as a young priest, and served briefly as an auxiliary bishop before succeeding Cardinal Sapieha as Archbishop of Krakow. He was elected Pope on October 16th, 1978.

He's remembered by us for a lot of things: the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the revised Code of Canon Law, the Third Edition of the Roman Missal, the expansion of the Holy Rosary to include the Luminous Mysteries, just to name a few. He wasn't a perfect pope by any means: he had a blind spot regarding sexual abuse by priests, probably because, in his native Poland, an accusation of sexual abuse was the primary means used by the Communists to get rid of priests who annoyed them, so he had a hard time taking such accusations seriously.

His twenty-seven years as pope left behind a voluminous amount of catechetical teaching, delivered in his many encyclicals and apostolic exhortations, but also in his weekly General Audience addresses, which he raised to a whole new level of importance, leaving the popes who followed him playing catch-up. It's not for the present generation to say, but I suspect that, in the decades and centuries to come, the importance of Pope Saint John Paul's catechetical influence on the Church will one day cause him to be regarded as a Doctor of the Church. Some people are already fond of calling him “John Paul the Great,” which is very improper: the title “Great” has only been bestowed a few times on Pope's who have been canonized, and never sooner than three hundred years after they're dead.

Every priest feels a spiritual and intellectual bond with whoever was pope at the time he was ordained, and for me that pope was Saint John Paul II; so, it was important to me to celebrate his memorial today even though its celebration is optional. As with most of the saints, most of us will venerate him for different reasons.  For myself, his most important contribution to the life of the Church is the one thing that most people know nothing or care nothing about: his lifting of the veil of suspicion from the works of the Spanish Mystics, paving the way for Teresa of Avila, John of the Cross and other Carmelite spiritual authors to offer an alternative to the rigid spiritual program imposed on the Church by the Jesuits and considered infallible for so many centuries (and it's ironic that the pope who canonized him was a Jesuit). For others, I suppose, his unwavering witness of persevering in his papal duties until death, even while in the throws of Parkinson's Disease, may be the most inspiring thing about his life; most certainly he is a saint to pray to for anyone suffering from painful and chronic illness. For myself, his most important contribution to the life of the Church is the one thing that most people know nothing or care nothing about: his lifting of the veil of suspicion from the works of the Spanish Mystics, paving the way for Teresa of Avila, John of the Cross and other Carmelite spiritual authors to offer an alternative to the rigid spiritual program imposed on the Church by the Jesuits and considered infallible for so many centuries (and it's ironic that the pope who canonized him was a Jesuit). For others, I suppose, his unwavering witness of persevering in his papal duties until death, even while in the throws of Parkinson's Disease, may be the most inspiring thing about his life; most certainly he is a saint to pray to for anyone suffering from painful and chronic illness.

In any case, on his memorial today let us all pray to him for Holy Mother Church, to whose patrimony of teaching Saint John Paul added with great clarity and zeal, and who's example of priestly life and service has inspired many to follow into the sacred ministry, yours truly included.

Turning now to today’s Gospel lesson, we find that it’s a repeat of one we heard way back in Lent; and, in the interests of full disclosure, so is the homily. And, since it’s been a while since I gave you a movie reference, we’ll have one today. In David Leen’s film, Lawrence of Arabia, there’s a scene where Lawrence, played by Peter O'Toole, has been summoned to the office of his commanding general, played by Jack Hawkins, and a reporter, played by Arthur Kennedy, asks Claude Rains, “Is the man in trouble?” and Rains, who plays a shifty and calculating diplomat, responds, “I assume so. We all have troubles”; which, of course, is not an answer, but is profoundly true. There are very few of us who can say that our journey through this valley of tears—as the “Hail, Holy Queen” puts it—is a happy-go-lucky waltz through life. The temptation, of course, is that we personalize our troubles and presume that they are directed personally against us because of some sin or some failure on our part, and if we could only identify it and deal with it all our troubles would go away. Remember when our Lord encountered the Man Born Blind, and His disciples asked him, “'Master, was this man guilty of sin, or was it his parents, that he should have been born blind?' 'Neither he nor his parents were guilty,' Jesus answered; 'it was so that God’s action might declare itself in him'” (John 9: 2-3 Knox).††

It's the same question they ask Him in today's lesson, just with different circumstances: an uprising among the Jews in our Lord's adopted home province of Galilee had been put down very violently by Pilate, and some sort of construction accident in Siloam had killed eighteen people while they were building some sort of tower or monument at the sight of Jacob's Well; so, the presumption of their question to Him is the same as in the case of the Man Born Blind: what did all these unfortunate people do to deserve all this?

This presumption, of course, is an exercise in the sin of pride, and our Lord challenges it in the first half of today's Gospel lesson:

Do you suppose, because this befell them, that these men were worse sinners than all else in Galilee? I tell you it is not so; you will all perish as they did, if you do not repent. …do you suppose that there was a heavier account against them, than against any others who then dwelt at Jerusalem? I tell you it was not so; you will all perish as they did, if you do not repent (Luke 13: 2, 4-5 Knox).

In other words, while it is true that all suffering in this earthly life is the result of sin, this does not mean that our own sufferings are the results of our own sins; and, I say that this is an exercise in the sin of pride because it's based on the presumption that the negative effects of God's permissive will are so personalized that what we do in this life effects us and us alone, without reckoning upon the Communion of the Saints or our participation in the effects of Original Sin. In other words, while it is true that all suffering in this earthly life is the result of sin, this does not mean that our own sufferings are the results of our own sins; and, I say that this is an exercise in the sin of pride because it's based on the presumption that the negative effects of God's permissive will are so personalized that what we do in this life effects us and us alone, without reckoning upon the Communion of the Saints or our participation in the effects of Original Sin.

Life in this world is hard, but not because of anything we've done personally, but because of the effects of our fallen nature and the concupiscence that goes with it. As our Lord points out, the Galileans and the people at Siloam were punished, yes, but not because of each of their individual sins, but because of the sins of all Galileans and all Siloamites; and, the repentance he exhorts upon them is a repentance that must take place within the whole of those societies. It only becomes personal when we realize that the conversion of a society is linked to the personal conversion of each and every soul within it; and, we contribute to the conversion of society by, first of all, converting ourselves.

The second half of the Gospel lesson is a parable, and a rather simple one: the fig tree that doesn't bear fruit is cut down and thrown away; not a lot of mental gymnastics needed to figure that one out. But the important part of this lesson is how dangerous it can be to become too introspective. This, also, is an exercise in pride—and for the same reason—because it presumes that everything that happens to me is because of me. It's an exercise in a lack of understanding of Catholic dogma because it denies the effects of Original Sin and our link to the Communion of the Saints. I suffer in this world not because I am a sinner, but because I happen to live in a sinful world. We chafe at that because it isn't fair: why should I have to participate in the negative effects of the sins of others? Because that's the way it is. That's what Original Sin was all about.

We often betray our sin of pride and our lack of understanding of Original Sin in the manner in which we sometimes make our confessions: we start crying to the priest about how hard our life is and how difficult it is to cope, either because we have mistaken the priest for some kind of psychologist or counselor, or—which I think is more likely—we're just obsessed with ourselves and presume that everything that's gone wrong with our lives has to do with us; and, this prevents us from making a truly good confession. We don't go to confession to get practical advice on how to cope with our problems; we go to confession to be absolved of our sins, and all the priest has to know to do that is what we did and how many times we did it, as far as we can remember. And I sometimes suspect that the reason so many people wait so long to go to confession, or avoid going to confession, is because they don't really understand what they're supposed to do there, or what they're supposed to be there to receive. It's purpose is not practical or psychological, it's sacramental; it's there to give Grace. Use it as some sort of free counseling session, and you rob it of it's grace. We often betray our sin of pride and our lack of understanding of Original Sin in the manner in which we sometimes make our confessions: we start crying to the priest about how hard our life is and how difficult it is to cope, either because we have mistaken the priest for some kind of psychologist or counselor, or—which I think is more likely—we're just obsessed with ourselves and presume that everything that's gone wrong with our lives has to do with us; and, this prevents us from making a truly good confession. We don't go to confession to get practical advice on how to cope with our problems; we go to confession to be absolved of our sins, and all the priest has to know to do that is what we did and how many times we did it, as far as we can remember. And I sometimes suspect that the reason so many people wait so long to go to confession, or avoid going to confession, is because they don't really understand what they're supposed to do there, or what they're supposed to be there to receive. It's purpose is not practical or psychological, it's sacramental; it's there to give Grace. Use it as some sort of free counseling session, and you rob it of it's grace.

While it should be consoling to know that our problems are not directed at us personally, the sin of pride is a persistent monster: we all want to think that we're special, and to learn that our personal problems have less to do with ourselves and what we've done than they do with a fallen nature we share with everyone else takes that away from us. The question we each must ask ourselves is: do I have the humility to accept the fact that it really isn't all about me?

Confession is a big part of our lives as Catholics, as you know; even more so during this Jubilee Year of Mercy. So, let's make a resolution that, the next time we sit down to make a good examination of conscience in preparation for confession, we'll do it this time without the overtones of self-pity, without rehashing for the priest—or even for ourselves—what So-and-so did to tempt us to say that uncharitable word, or what aches or pains caused us to be grumpy and disagreeable, or whatever. “I take no pleasure in the death of the wicked man,” says the Alleluia I sung for you before the today’s Gospel lesson, taken from the words of the Prophet Ezekiel (33: 11), “but rather in his conversion that he may live.”

* As this memorial is new the Church, suggested lessons for the proper have yet to be assigned.

** Note that the ordo at Rorate Cæli is wrong: it continually indicates the first lesson from the primary common, without reference to the seasonal adjustments on the Marian ferias on Saturdays.

*** The Gradual is non-Scriptural: "Blessed and venerable art Thou, O Virgin Mary: Who without blemish to Thy maidenhood, wert found to be the Mother of the Saviour. O Virgin, Mother of God, He Whom the whole world cannot contain, enclosed Himself in Thy womb and became Man."

† Abercius was Bishop of Hiropolis in Phrygia at the time of Emperor Marcus Antonius (161-180). He died toward the end of the second century. In the custom of many early Christians, he inscribed his own tombstone, which gives an account of his life, travels and faith, thanking Christ for the gift of his faith, expressing his love for the Mother of God, and exhorting all who see it to pray for him. It is now in the Lateran Museum.

The Seven Holy Children, all blood brothers, were sealed alive in a cave as punishment for their faith by the Emperor Decius c. 250. An ancient legend claims that, after three hundred years, they came out alive; however, note that this same story is told in the Quran regarding three Muslim brothers.

†† Verse 2: “Kαὶ ἠρώτησαν αὐτὸν οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ λέγοντες: ῥαββί, τίς ἥμαρτεν, οὗτος ἢ οἱ γονεῖς αὐτοῦ, ἵνα τυφλὸς γεννηθῇ[?]” The footnote provided by Msgr. Knox is worth repeating: “The disciples may not have known that the man was born blind; and [the] Greek may be interpreted as meaning, ‘Did this man sin (and go blind)? Or did his parents commit some sin, with the consequence that he was born blind?’”

|