And That's the Way It Is. Or Is It?

Lessons from cycle A of the Dominica, according to the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite:

Isaiah 45: 1, 4-6.

Psalm 96: 1, 3-5, 7-10.

I Thessalonians 1: 1-5.

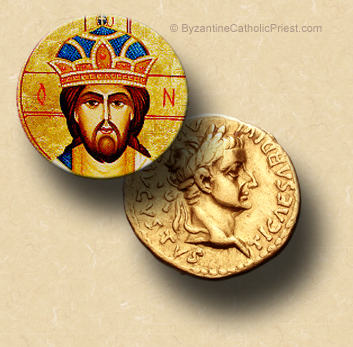

Matthew 22: 15-21.

The Twenty-Ninth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

9:06 AM 10/19/2014 — Today, if you will allow—and, of course, there's not a lot you can do about it even if you don't—I would like to deviate from the lessons presented to us at Holy Mass and reflect with you about something else entirely, something that has been coming up quite frequently in confession, and which I believe needs to be addressed in a general way, and that is the difficulty that so many of us are having coping with everything that seems to be going on the world today. We watch the news, we see the threat of terrorism and war, Ebola and the failure—or even the unwillingness—of the government to do anything about it, the controversial questions of illegal immigration, pastors in one particular state having their sermons subpoenaed because they've spoken critically of homosexuality, and on and on and on; and, it gets us upset and angry and agitated and becomes very damaging and disturbing to our interior life, sometimes to the point that we find it difficult to pray. It generates in us an interior anger that is very difficult to shake off. We try to find solace in our prayers; but, when one is angry inside, it's hard to place ourselves in the presence of God. It's been coming up a lot in confession, which is why I thought it's important to address the problem. 9:06 AM 10/19/2014 — Today, if you will allow—and, of course, there's not a lot you can do about it even if you don't—I would like to deviate from the lessons presented to us at Holy Mass and reflect with you about something else entirely, something that has been coming up quite frequently in confession, and which I believe needs to be addressed in a general way, and that is the difficulty that so many of us are having coping with everything that seems to be going on the world today. We watch the news, we see the threat of terrorism and war, Ebola and the failure—or even the unwillingness—of the government to do anything about it, the controversial questions of illegal immigration, pastors in one particular state having their sermons subpoenaed because they've spoken critically of homosexuality, and on and on and on; and, it gets us upset and angry and agitated and becomes very damaging and disturbing to our interior life, sometimes to the point that we find it difficult to pray. It generates in us an interior anger that is very difficult to shake off. We try to find solace in our prayers; but, when one is angry inside, it's hard to place ourselves in the presence of God. It's been coming up a lot in confession, which is why I thought it's important to address the problem.

Now, I haven't been here at the Shine all that long, so most of you don't know me all that well, but before coming here I had been, for over sixteen years, pastor of two parishes. The last four years of that time my health had started to deteriorate; I had been in and out of the hospital a lot, had a couple of surgeries, and spend the last two years of that time virtually an invalid, more or less confined to the rectory except when they would prop me up in church on Sundays; but, obviously, the level of ministry I was able to provide to my parishes had become minimal, and the parishes suffered as a consequence, so they took my parishes away from me.

I've bounced back pretty well, as you can see, but still have a number of problems which I'm able to manage so long as I pace myself and don't spend too much time on my feet at one time. But the experience of being an invalid at home was a very formative one, and those of you who have been or who are in that situation will know what I'm talking about. When you're in a condition where it can be painful just to move around, you have the unfortunate tendency to park yourself in front of the television for long periods of time, and this can really screw you up, especially if what you've got on is the news. It is very easy to watch the news and become upset or depressed or angry or all of the above, and to think that the world is simply coming apart at the seams; but is it really? I actually had a conversation not long ago with someone who was complaining about how upset she was about everything that she was seeing in the news, and I don’t think she was expecting the advice I gave her, because my advice to her was to switch it off. It’s like that old joke where the man goes in to see his doctor and he says, “Doctor, it hurts when I do this.” And the doctor replies, “Then, don’t do that.” If watching the news upsets us, why is the advice to simply turn it off not acceptable to us? Because we’re afraid that if we do, we’re going to miss something; or, maybe its because we've convinced ourselves that, if we don't keep ourselves informed, that means we're apathetic and don't care.

But what is it exactly we think we’re going to miss, and what do we think we can do about it? Some of you, I'm sure, are old enough to remember when television news first started. TV networks first began broadcasting news in the late 1950s; before then, you got your news either from the paper or from the newsreel at the movie theater.  For almost twenty years, the CBS Evening News consisted of Edward R. Murrow reading headlines from the papers for fifteen minutes, without commercials, followed immediately by that week's episode of "Milton Berle." There were no pictures, no reporters "on the scene," no experts to tell us what it all meant; and it was over in a quarter of an hour. Was that because there was much less going on than there is now? For almost twenty years, the CBS Evening News consisted of Edward R. Murrow reading headlines from the papers for fifteen minutes, without commercials, followed immediately by that week's episode of "Milton Berle." There were no pictures, no reporters "on the scene," no experts to tell us what it all meant; and it was over in a quarter of an hour. Was that because there was much less going on than there is now?

Before he died, Murrow was very candid about the debate that went on at the time as to whether this new thing called "Television Journalism" should become commercial. The networks that broadcast news reports did so gratis; there was no revenue generated by it. Some—including Murrow—thought it would be a mistake for news to attempt to make money because it would corrupt it's objectivity. The decision to advertize on news broadcasts extended the time needed from fifteen minutes to a half hour; and, suddenly, finding ways to make people watch your channel instead of the other guy's became important. Hence, live reports from the scene, expert commentary, human interest ("Here's a neighbor who will tells us what a nice quiet man the ax murderer was," or "How do you feel about your children being eaten by a python?"), and, eventually whole shows devoted to commentary, none of which contributed in any way to the transmission of essential and needed information, but hopefully made the whole thing more entertaining than the other channel.

When twenty-four hour cable news channels first appeared some twenty years ago, the idea wasn't that anyone would watch the news for twenty-four hours; the idea was that someone could catch ten or fifteen minutes of essential news when they had time to watch it, instead of having to schedule their day around some stupid broadcast. I challenge you to watch the news for twenty-four hours and identify four major stories that are new or have changed substantially in that period. After all, the man who reads the news to you on TV in the evening is not going to come on and say, “Well, folks, nothing much new happened today, so you might was well go watch Sienfeld re-runs.”

Remember that journalism is not a public service; it’s a business. It makes its money by selling advertising, but advertising doesn’t make any money unless a lot of people are watching. So, the talking head spouting news at you has a commercial interest in doing everything he can to make sure your eyes and ears are glued on him and his channel as often and as long as possible. So, no matter what is actually happening in the world—or not happening as the case may be—he’s got to find a way to make sure you think the world is falling apart, and you’d better darn well watch it or you’re gonna miss it. If he’s got footage of some explosion or battle, he’ll play it for you over and over again, each time embellishing it with even more intense descriptions of the carnage; then he’ll truck out the ubiquitous panel of experts and analysts and retired generals who will each tell you how this is, indeed, the most important and critical thing that has ever happened in the history of the universe. And if you so much as leave to go to the kitchen and get a Coke, you’ll be sorry because you’ll miss the end of the world. Maintaining our spiritual equilibrium and tending to our interior life is difficult enough in today's world; allowing ourselves to become saturated with information overload in the form of this kind of mercenary propaganda makes it practically impossible.

My point is simply this: world events are not unfolding any faster than they have in the past, and the world is not falling apart at the seams. If it seems that way, that’s because the events of the day are being packaged and repackaged in an ever increasing sensationalistic way for the purpose of doing exactly what they're doing: causing us to park our rear ends in front of the TV, getting us all hot and bothered over events about which we can do nothing; nothing, of course, except pray, which we should be doing every day anyway. So, the advice of the doctor in the joke is actually quite sound: “Doctor, it hurts when I do this.” “Then, don’t do that.”

“Father, I get upset when I watch the news.” “Then, don’t watch the news.” I can guarantee that, if the world comes to an end, you’re not going to miss it because you weren’t watching the news.

|