There's No Shame in Being Poor, only Poorly Dressed.

Lessons from cycle A of the Dominica, according to the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite:

Isaiah 25: 6-10.

Psalm 23: 1-6.

Philippians 4: 12-14, 19-20.

Matthew 22: 1-14.

The Twenty-Eighth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

2:46 PM 10/12/2014 — “Jesus said to his disciples.…” Whenever we get a gospel lesson that begins with that phrase, we know we're about to get a parable. Over the centuries, the Church has given these parables names, which is how we typically refer to them today. Today's gospel lesson, for example, is familiar as “The Parable of the Marriage Feast” or “The Parable of the Wedding Banquet” or something similar. That's a lot less cumbersome than calling it “The Parable of Matthew, Chapter Twenty-two, verses one through fourteen.” When I post my homilies on my personal web site for anyone to read I tend to give them my own titles, which you would only know if you went to read them there, since I don't mention it at Holy Mass; and, the last time I preached on this Gospel lesson I gave it the title “There's No Shame in Being Poor, only Poorly Dressed.” 2:46 PM 10/12/2014 — “Jesus said to his disciples.…” Whenever we get a gospel lesson that begins with that phrase, we know we're about to get a parable. Over the centuries, the Church has given these parables names, which is how we typically refer to them today. Today's gospel lesson, for example, is familiar as “The Parable of the Marriage Feast” or “The Parable of the Wedding Banquet” or something similar. That's a lot less cumbersome than calling it “The Parable of Matthew, Chapter Twenty-two, verses one through fourteen.” When I post my homilies on my personal web site for anyone to read I tend to give them my own titles, which you would only know if you went to read them there, since I don't mention it at Holy Mass; and, the last time I preached on this Gospel lesson I gave it the title “There's No Shame in Being Poor, only Poorly Dressed.”

Of course, our attention is right away drawn to the circumstances of the invited guests refusing to come to the wedding, of the king having his servants drag in all these strangers off the street to replace them, then one of these being tossed out because he's not properly dressed; and, as I mentioned to you two weeks weeks ago, if we allow ourselves to judge our Lord's parables as we would some drama we read in a book or watch on television, we would judge them pretty harshly, especially today's lesson, since the behavior of the king doesn't make any sense: how could he legitimately expect someone to be dressed properly for a wedding when the only reason he's there is because he was dragged in off the street at the last minute?

And here's another good opportunity to try to understand exactly what a parable is, especially as they are used as teaching tools by our Lord. Part of the problem is that the parable as used by our Lord is a particular Middle Eastern form of teaching which, for one reason or another, has a hard time penetrating our literal, Western minds.

One of my closest friends is a priest stationed some distance away, and once in a while we will watch an old movie on television while talking on the phone, and pick apart what we think is wrong with the movie, saying things to each other like, “Did they really expect the audience to buy that?” It's very easy to do that with the parables of our Lord because, like most Middle Eastern parables, they don't make logical sense. They're not meant to.

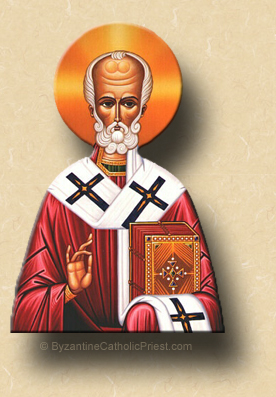

One good way to look at a parable is to consider it to be a sort of verbal icon. Most of you know that I spent many years serving in an Eastern Catholic Church and, as you know, icons are a very important part of the spirituality of Eastern Christianity;  and, while most of you, I'm sure, would be able to identify a Byzantine icon when you see one, very few people truly know how to read them properly. They are not meant to be realistic representations. When our Lord or a saint is depicted in an icon, he does not look like a normal human being: the head and eyes are much too large, the mouth is much too small, almost as if the saint being represented is some sort of space alien; but, those distorted features speak volumes. The head is large in proportion to the body because the saint contemplates the will of God; the eyes are large and the mouth is small because the saint's eyes of faith are always alert for the will of God, which he obeys without question or comment. If he's a bishop, he holds one hand in a blessing and the book of the Gospels in the other; if he's a martyr, he'll often hold instruments of the passion. The icon is not meant to show us the saint as he actually looked when he walked this earth, but rather to show us, in a symbolic and mystical way, the primary features of why he's a saint. and, while most of you, I'm sure, would be able to identify a Byzantine icon when you see one, very few people truly know how to read them properly. They are not meant to be realistic representations. When our Lord or a saint is depicted in an icon, he does not look like a normal human being: the head and eyes are much too large, the mouth is much too small, almost as if the saint being represented is some sort of space alien; but, those distorted features speak volumes. The head is large in proportion to the body because the saint contemplates the will of God; the eyes are large and the mouth is small because the saint's eyes of faith are always alert for the will of God, which he obeys without question or comment. If he's a bishop, he holds one hand in a blessing and the book of the Gospels in the other; if he's a martyr, he'll often hold instruments of the passion. The icon is not meant to show us the saint as he actually looked when he walked this earth, but rather to show us, in a symbolic and mystical way, the primary features of why he's a saint.

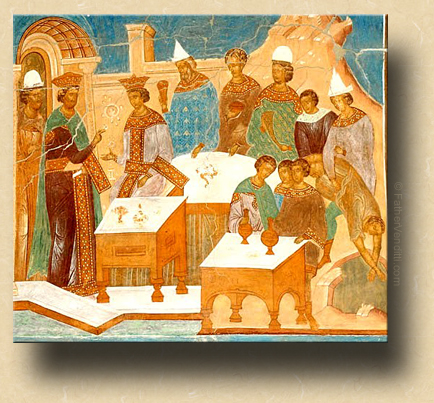

A parable is the same sort of thing, except it's all done with words instead of pigments. The story of the parable is not supposed to make sense; the events of the story symbolize deeper realities. In the case of today's Gospel lesson, it's not supposed to make sense that the king in the story drags people in from off the street to attend a wedding, then throws one of them out because he doesn't have a tuxedo; it's a lesson about the history of salvation. The invited guests who refused to attend represent the Israelites, who were God's chosen, but who rejected salvation; the poor people dragged in off the street to take their place were the Gentiles; and the poor guy who gets tossed represents those among the Gentles who, even after being offered this great gift of salvation, rejected it anyway. And we can liken him to our own situation by contemplating that most of us were born into the Church;—we didn't choose the life of a Catholic for ourselves—but, even though the decision was made for us as children, we still, at some point, had to make a decision to either live according to that choice or to reject it. And that decision can be made at any time. Which is why it's so important to educate our children in the faith and give good example of Christian living to them; because, without this preparation, there is the danger that, without the knowledge of the true faith and good example to follow, they'll reject it the first chance in their lives they encounter temptation.

That's what the fellow who is thrown out of the wedding represents. He's like a baby who is baptized but who is given no appreciation for the great gift that's been given him. His parents thought they were doing right by him by bringing him to be baptized, but that's all they did for him. They didn't bother to teach him anything; and, even if they did make a minimal effort by making him go to Sunday school, they didn't provide the proper example of practicing the faith fervently themselves, so he had no reason to think that what he was being taught was important.

Whenever we hear a story about a priest refusing to baptize a baby because he doesn't know the parents—or he does know them but knows that they're not practicing—we tend to judge that priest very harshly and accuse him of “punishing the baby for the sins of the parents”; but, the priest who baptizes any baby who comes down the pike does that child no favors. When that child eventually stands before the judgment seat of Christ, as we all must one day, he won't be judged simply as a conscientious person who had no knowledge of Christ and his Church; he'll be judged as a baptized Catholic who should have known better.

In the beginning of our Lord's parable, the original invited guests give two primary reasons for not attending: as our Lord tells it, “…they paid no heed, and went off on other errands, one to his farm in the country, and another to his trading” (Matt. 22: 5 Knox); the two principle reasons people give for not coming to church on any particular Sunday: a family obligation or “I have to work.” It's a question of priorities, and the last priority is always the faith. Except that, years later, when they're on their death beds, suddenly they wish that they had had different priorities.

The last line of our Lord's parable is pithy enough: “Many are called, but few are chosen.” But it's important to realize that the chosen are not chosen at random; they make the choice themselves. They make the choice by deciding that they will not be among those caught not properly dressed for the feast. They make the choice by making sure that they know the faith, live their faith, and nourish their faith by frequenting the Holy Sacraments, and teaching their children to do the same, not by dropping them at CCD every week, but by giving them good example.

|