Talk Is Cheap.

The Twenty-Sixth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the primary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ezekiel 18: 25-28.

• Psalm 25: 4-9.

• Philippians 2: 1-11.

[or, Philippians 2: 1-5.]

• Matthew 21: 28-32.

The Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ephesians 4: 1-6.

• Psalm 32: 12, 6.

• Matthew 22: 34-46.

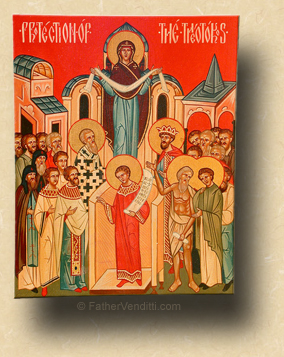

The Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost (the Second after the Holy Cross); the Solemn Holy Day of the Protection of the Theotokos; the Feast of the Holy Apostle Ananias; and, the Feast of Our Venerable Father Romanos the Hymnographer.*

First & fourth lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fifth from the menaion for the Mother of God, third & sixth from the menaion for the Apostle, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• II Corinthians 6: 16—17: 1.

• Hebrews 9: 1-7.

• I Corinthians 4: 9-16.

• Luke 6: 31-36.**

• Luke 10: 38-42; 11: 27-28.

• Luke 10: 16-21.

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:27 AM 10/1/2017 — Those of you who have been with us here on Sundays regularly may be tempted to think that I'm some sort of “one note Charlie,” saying the same thing over and over again, but that's only because the lessons we've been reading on Sundays from the Holy Gospel keep saying the same thing over and over again: God's ways are not our ways, God's justice contains no notion of “fairness” as we have come to understand it, and reward and punishment do not come in this life but in the next. And I can only suppose that the reason Our Blessed Lord keeps telling parables that make this point is because of His own sense of human frustration. As God, Our Lord knew everything, but as Man he certainly experienced all the emotions and frustrations that are part of the human condition: he wept at the tomb of His friend Lazarus, even though He knew He was going to raise Lazarus from the dead; He blew up at the money changers in the Temple; He cried tears of blood in the garden the night before He died, even though He knew that He would rise from the dead. He wasn't play-acting when he did these things; these were the real emotional responses of someone who, even though He was God, chose of His own free will to become a Man in order to pay the just penalty of death for the sins of all mankind. Sometimes we forget that. The doctrine of Original Sin is very easy to forget: all of us are conceived and born into a state of sin, which makes going to heaven impossible without atoning for that sin in blood; but, God loved us so much that He chose, of His own free will, to become one of us so that He could pay that penalty for us. He had to become a Man to do it, because the Original Sin was committed by a man, and only another man could make up for it. Why would God do that when He could have just as easily allowed us all to go the hell? Because He loves us. 8:27 AM 10/1/2017 — Those of you who have been with us here on Sundays regularly may be tempted to think that I'm some sort of “one note Charlie,” saying the same thing over and over again, but that's only because the lessons we've been reading on Sundays from the Holy Gospel keep saying the same thing over and over again: God's ways are not our ways, God's justice contains no notion of “fairness” as we have come to understand it, and reward and punishment do not come in this life but in the next. And I can only suppose that the reason Our Blessed Lord keeps telling parables that make this point is because of His own sense of human frustration. As God, Our Lord knew everything, but as Man he certainly experienced all the emotions and frustrations that are part of the human condition: he wept at the tomb of His friend Lazarus, even though He knew He was going to raise Lazarus from the dead; He blew up at the money changers in the Temple; He cried tears of blood in the garden the night before He died, even though He knew that He would rise from the dead. He wasn't play-acting when he did these things; these were the real emotional responses of someone who, even though He was God, chose of His own free will to become a Man in order to pay the just penalty of death for the sins of all mankind. Sometimes we forget that. The doctrine of Original Sin is very easy to forget: all of us are conceived and born into a state of sin, which makes going to heaven impossible without atoning for that sin in blood; but, God loved us so much that He chose, of His own free will, to become one of us so that He could pay that penalty for us. He had to become a Man to do it, because the Original Sin was committed by a man, and only another man could make up for it. Why would God do that when He could have just as easily allowed us all to go the hell? Because He loves us.

This Baltimore Catechism moment has been brought to you by today's Gospel lesson, because there is no way to understand the parable Our Blessed Lord tells today without reminding ourselves that Our Lord's Humanity was real. Oh, there were some heretics in the third and fourth centuries who floated the idea that Jesus wasn't a real man, that He just appeared to be a man, just as there were some who tried to explain things by suggesting that Jesus wasn't really God, just a man who was specially blessed by God; but, suggesting that Jesus wasn't a real man is just as wrong as suggesting that He wasn't really God because, if He wasn't a real man, then his death on the Cross could not possibly save us. The penalty had to be paid by one of us for all of us. Those of you who follow pop culture may remember a song sung by Joan Osborne in 1995 entitled, “What if God Were One of Us?” Clearly, Ms. Osborne has never read either the Baltimore Catechism or the Gospel of Jesus Christ, for, if she had, she would have known that God is one of us. Actually, the song was written by Eric Bazilian of the Hooters; but, before you get distracted with why Father Michael even knows that fact, let's return to the Gospel lesson.

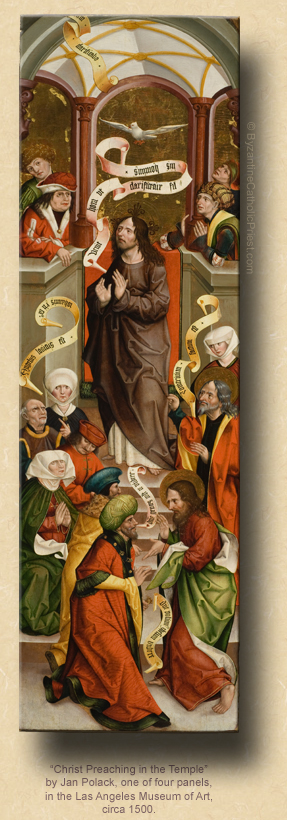

As you know, Our Lord is constantly teaching, and every teacher has his or her own style. Socrates taught by asking questions. Our Lord uses a Jewish rabbinic style: he tell stories; we call them parables. They're not meant to be gripping yarns; in fact, as stories go, they're pretty pedestrian and sometimes even implausible; the characters in them don't usually act they way normal people do.  That's because they're not meant to be realistic; they're meant to make a point; and the line between right and wrong, good and evil, in the parables is drawn very boldly. And the points Our Lord makes in His parables are all very simple; you don't need a secret decoder ring to figure them out. Today's parable is a good example: two fellows are asked by their father to go work in the family vineyard; one of them is very rude to his father and says that he won't go, but then feels guilty about it and goes anyway; the other one bows and scrapes before his father and says, “Oh, yes, father, I'm going right now,” then plays hooky and doesn't go. Our Lord then asks the question, “Which of the two did his father's will?” (Matt. 21: 31 NABRE). That's because they're not meant to be realistic; they're meant to make a point; and the line between right and wrong, good and evil, in the parables is drawn very boldly. And the points Our Lord makes in His parables are all very simple; you don't need a secret decoder ring to figure them out. Today's parable is a good example: two fellows are asked by their father to go work in the family vineyard; one of them is very rude to his father and says that he won't go, but then feels guilty about it and goes anyway; the other one bows and scrapes before his father and says, “Oh, yes, father, I'm going right now,” then plays hooky and doesn't go. Our Lord then asks the question, “Which of the two did his father's will?” (Matt. 21: 31 NABRE).

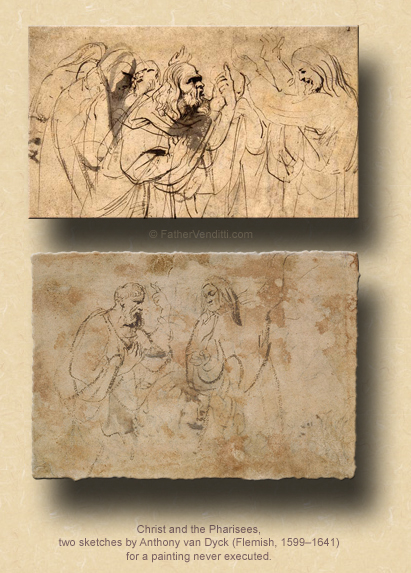

The rabbis He's speaking with get the answer right, of course; how could they not? It's not a difficult question. But, whether they've applied the lesson of the parable to themselves is another matter. And the clue that Our Lord is experiencing a very human kind of frustration—perhaps even anger—in this encounter with these Jewish priests and temple elders is suggested in what he says to them after they've answered the question: “Amen, I say to you, tax collectors and prostitutes are entering the kingdom of God before you” (v. 31 NABRE). He couldn't have chosen a more insulting thing to say to them. The Greek word that's actually used here is προάγουσιν, from which comes the English word to progress or move forward or, literally, “move ahead of.” Think about that. Here are the holy men of Jewish society in Jerusalem, the priests and elders of the Temple;—think of them as your pastor and the parish council—and, Msgr. Knox, in his translation, captures what Our Lord is actually saying: that tax collectors and prostitutes are “further on the road to God’s kingdom than you” (v. 31 Knox). Our Lord couldn't have chosen two examples more insulting with which to compare these people. It's one thing to sin out of weakness, as we all do;—that's why we go to confession—but, a prostitute is someone who makes her living by means of sin.  And as for tax collectors … well, who doesn't hate the IRS? And Our Lord is telling them that both of these kinds of people are further along the road to holiness than they are. And as for tax collectors … well, who doesn't hate the IRS? And Our Lord is telling them that both of these kinds of people are further along the road to holiness than they are.

The basic point of Our Lord's parable is neither earth-shattering nor profound:—very few of his parables are—he's simply reminding them of how important it is for them to practice what they preach, the point of the parable being that it's not what you say that's important; it's what you do that matters. That's sound advice for any priest or rabbi or minister or anyone who, because of his vocation, has to speak for God; it's not exactly rocket science. Could the point have been made more gently? Of course. So, why does He resort to shock and awe? And here is where we must read between the lines and appreciate what is clearly Our Lord's sense of human frustration. It wasn't that the rabbis and temple fathers didn't understand the point of the parable;—they got the answer to the question right, so they understood the lesson—but they had failed to apply it to themselves. And don't we do exactly the same thing? We come to Holy Mass, we hear the Word of God proclaimed to us, we hear the homily of the priest who attempts to apply the words of Our Lord to our own lives; and yet, what is it we so often find ourselves thinking? “Gee, I hope So-and-so heard that!” And that's only if we're thinking anything at all, other than, “I hope he shuts up soon because it's time for lunch.”

Well, he's going to shut up right now, but here's the point: it isn't enough to come to Mass on Sunday; it isn't even enough to pray the Mass with devotion, as important as that is. What really matters is what we do after it's over, how hearing the Holy Word of God and receiving Our Lord's Sacred Body and Precious Blood causes us to live our lives. As we reflected at the beginning, Our Blessed Lord did all this for us simply out of His raw, unbridled love for us, which we have done nothing to merit. We can't even begin to contemplate the reason why He loves us so, but what we can do is begin to consider how we can live our lives in response.

* Today is called "The Second Sunday after the Holy Cross" because the Sunday following the feast, "The Sunday after the Exaltation," is considered part of the Postfestive period of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, and thus part of the feast itself. Following the feast and postfestive period of the Holy Cross (Sept. 14th through 21st), the Greek Church actually labels these Sundays as “Sundays after the Holy Cross” and begins to number them accordingly, calling today "The First Sunday after the Holy Cross," while the Ruthenian and Russian Churches continue to number them as "Sundays after Pentecost" (though in some older Ruthenian typicons the Greek custom is observed). The historical context of this custom was the Greek practice of marking the birthday of the Emperor Augustus on September 23rd, which they regarded as the first day of the Church year. It was not until the fall of the empire that the new year observance was moved to Sept. 1st throughout the Churches of the Byzantine Rite.

The Solemn Holy Day of the Protection is one of the most important feasts on the Byzantine calendar. It commemorates an appearance of the Mother of God near Constantinople in the tenth century, during the siege of Constantinople by the Vandals. During services in the Church of Our Lady of the Waves in Blachernes, which was a seaside monastery on the outskirts of Constantinople, St. Andrew and his disciple, St. Epiphanius, saw the Mother of God approaching the ambo. She was supported by many saints. Here She knelt in prayer before the Holy Table, Her face bathed in tears. After praying, She took off her veil and extended it over the people as a sign of Her protection. In the popular icon of this event, the Theotokos is seen standing above the faithful, Her arms outstretched in prayer and draped with a veil. St. Andrew and St. Epiphanius are shown along with many other saints. In the center of the church, on the ambo, stands a young man, clothed in a deacon’s sticharion, and holding in his left hand an open scroll with the text of the Christmas Kontakion written on it; he is St. Romanos the Melodist, the famous hymnographer whose feast is also celebrated on October 1st, and who is responsible for having composed many of the troparia and kontakia sung in the Liturgy of the Byzantine Churches. Pope-emeritus Benedict regarded Romanos as a Father of the Church, and devoted one of his weekly audience addresses to his life and work. A massive icon of the Protection graces the ceiling of St. Michael the Archangel Byzantine Catholic Church in Allentown, Pennsylvania, where I was pastor for almost fifteen years. The Solemn Holy Day of the Protection is one of the most important feasts on the Byzantine calendar. It commemorates an appearance of the Mother of God near Constantinople in the tenth century, during the siege of Constantinople by the Vandals. During services in the Church of Our Lady of the Waves in Blachernes, which was a seaside monastery on the outskirts of Constantinople, St. Andrew and his disciple, St. Epiphanius, saw the Mother of God approaching the ambo. She was supported by many saints. Here She knelt in prayer before the Holy Table, Her face bathed in tears. After praying, She took off her veil and extended it over the people as a sign of Her protection. In the popular icon of this event, the Theotokos is seen standing above the faithful, Her arms outstretched in prayer and draped with a veil. St. Andrew and St. Epiphanius are shown along with many other saints. In the center of the church, on the ambo, stands a young man, clothed in a deacon’s sticharion, and holding in his left hand an open scroll with the text of the Christmas Kontakion written on it; he is St. Romanos the Melodist, the famous hymnographer whose feast is also celebrated on October 1st, and who is responsible for having composed many of the troparia and kontakia sung in the Liturgy of the Byzantine Churches. Pope-emeritus Benedict regarded Romanos as a Father of the Church, and devoted one of his weekly audience addresses to his life and work. A massive icon of the Protection graces the ceiling of St. Michael the Archangel Byzantine Catholic Church in Allentown, Pennsylvania, where I was pastor for almost fifteen years.

** The four Gospels are all read in their entirety in the Byzantine Churches, and the reading of each begins with a great feast. The Gospel of St. John begins with the Feast of Feasts, Pascha, and is read until Pentecost. The Gospel of St. Matthew begins with Pentecost, and is read until the Feast of the Holy Cross, after which the Gospel of St. Luke is read all the way through until the Great Fast; but, because the Divine Liturgy is offered only on Saturday and Sunday in the Great Fast, the left-over passages are read in the last six weeks of the Matthean and Lucan cycles. This is why the Byzantine Churches begin the reading of Luke’s Gospel on the Sunday after the Holy Cross no matter where they are in the cycle of "Sundays after Pentecost." The Epistles, on the other hand, are read continuously without any adjustment, creating a discrepancy between Epistle and Gospel. This year, there is a discrepancy of two weeks until Dec. 28th. In the Byzantine Churches, this is commonly called "the Lucan Jump." Thus, today, the Epistle sung is the one for the Seventeenth Sunday, and the Gospel the one ordinary sung on the Nighteenth Sunday.

|