The Poor Man's Epiphany, Part Two: Our Own Star to Follow.

In the United States:

The Solemnity of the Epiphany of the Lord.

Lessons from the proper, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 60: 1-6.

• Psalm 72: 1-2, 7-8, 10-13.

• Ephesians 3: 2-3, 5-6.

• Matthew 2: 1-12.

|

Outside the United States:

The Second Sunday after the Nativity.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Sirach 24: 1-2, 8-12.

• Psalm 147: 12-15, 19-20.

• Ephesians 1: 3-6, 15-18

• John 1: 1-18.

|

The Sunday after the Octave Day of the Nativity: the Second Class Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Acts 4: 8-12.

• Psalm 105: 47.

• Luke 2: 21.

FatherVenditti.com

|

4:47 PM 1/5/2020 — If ever there was a feast on our calendar with a confusing history, it's the Epiphany. The name comes from a variation of the Greek language called “Koine Greek” (ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος, meaning “the common dialect”), a low-class sort of colloquial form of Greek, now a dead language, used throughout the Hellenistic regions of the Roman Empire, and is the dialect in which most of the New Testament was written. Ἐπιφάνεια, in this dialect, means “manifestation” or “striking appearance.” In the Eastern Churches, the feast is called Theophany, which comes from the same word in classical Greek, Θεοφάνεια, which literally translates as “the vision of God.” The traditional date for the feast has always been January 6th, but in the United States it's always transferred to the Sunday following the Octave of Christmas.* 4:47 PM 1/5/2020 — If ever there was a feast on our calendar with a confusing history, it's the Epiphany. The name comes from a variation of the Greek language called “Koine Greek” (ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος, meaning “the common dialect”), a low-class sort of colloquial form of Greek, now a dead language, used throughout the Hellenistic regions of the Roman Empire, and is the dialect in which most of the New Testament was written. Ἐπιφάνεια, in this dialect, means “manifestation” or “striking appearance.” In the Eastern Churches, the feast is called Theophany, which comes from the same word in classical Greek, Θεοφάνεια, which literally translates as “the vision of God.” The traditional date for the feast has always been January 6th, but in the United States it's always transferred to the Sunday following the Octave of Christmas.*

And from hearing today's Gospel lesson from Saint Matthew, you can tell that we are meant to commemorate today the visit of the Magi to the manger. The Magi are pagans—some translations call them “astrologers from the East”—who come to do homage to God become Man. They've come to know about the Incarnation of God into this world through their own mystical means, and their desire to worship God as an infant is a precursor of Christ's completion of salvation history: they are a prefiguring of the Gentiles who will be converted to the faith by Saint Paul, and announce from the very beginning of our Blessed Lord's life on earth that He has come to save all mankind. Both of the other lessons read on this day testify to this fact. Isaiah prophesies: “Lift up thy eyes and look about thee; who are these that come flocking to thee? Sons of thine, daughters of thine, come from far away…” (60: 4 Knox); and, the Blessed Apostle Paul, himself, tells us “that through the gospel preaching the Gentiles are to win the same inheritance, to be made part of the same body, to share the same divine promise, in Christ Jesus” (Eph. 3: 6 Knox).

Obviously, the Epiphany is a feast of deep mystical significance. But, instead of all that, I would like to take you back a week to last Wednesday and the Solemnity of Mary the Mother of God.

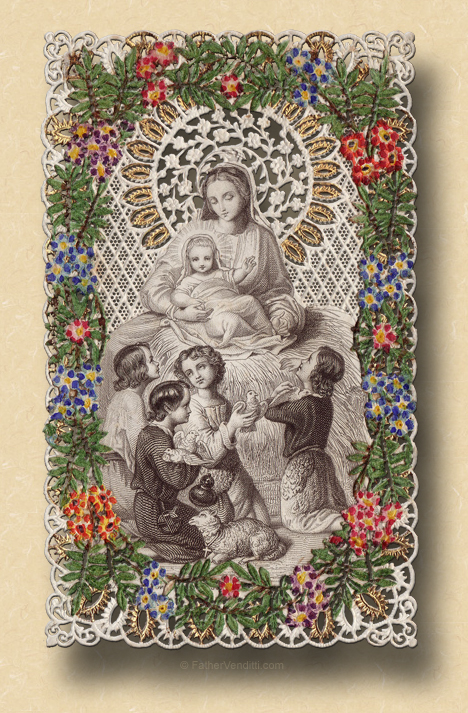

The Gospel lesson for that day presented to us another kind of Epiphany: not the visit of the Magi, but the visit of the shepherds, and you might recall how I contrasted the visits of the two different groups of men.  Consider any of the traditional artistic depictions of the Epiphany you may have seen, or even right here in our own Nativity set: the Magi are always shown dressed to the teeth in all their finery, usually with crowns on their heads; and, they're certainly not empty-handed, their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh borne in elaborate treasure chests. But you don't see too many artistic renderings of the visit of the shepherds. On New Years Day I had called the visit of the shepherds a kind of Spike TV version of the Epiphany: they're scruffy-looking because they're shepherds; they haven't brought anything with them; they tell Mary and Joseph this bizarre tale about how they heard about the birth of their Son from some invisible choir of angels. And I do remember mentioning that there are very few commentaries on those verses. Everyone, from the Fathers of the Church of the second century to Pope-Emeritus Benedict, wax eloquent about the visit of the Magi and its theological implications, dazzling us with thoughts about the mystical significance of the gifts they bring, and so forth; but, nobody seems to have anything to say about the shepherds or what they're doing there. Consider any of the traditional artistic depictions of the Epiphany you may have seen, or even right here in our own Nativity set: the Magi are always shown dressed to the teeth in all their finery, usually with crowns on their heads; and, they're certainly not empty-handed, their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh borne in elaborate treasure chests. But you don't see too many artistic renderings of the visit of the shepherds. On New Years Day I had called the visit of the shepherds a kind of Spike TV version of the Epiphany: they're scruffy-looking because they're shepherds; they haven't brought anything with them; they tell Mary and Joseph this bizarre tale about how they heard about the birth of their Son from some invisible choir of angels. And I do remember mentioning that there are very few commentaries on those verses. Everyone, from the Fathers of the Church of the second century to Pope-Emeritus Benedict, wax eloquent about the visit of the Magi and its theological implications, dazzling us with thoughts about the mystical significance of the gifts they bring, and so forth; but, nobody seems to have anything to say about the shepherds or what they're doing there.

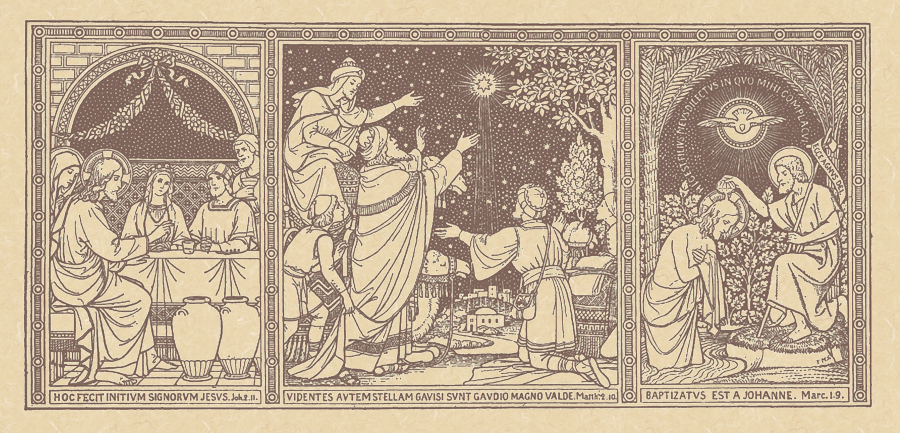

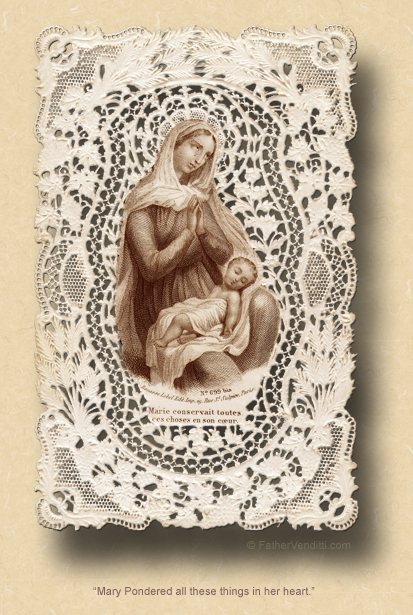

Both groups of men have fantastic stories to tell about how they came to know about the birth: the shepherds are hearing choirs of angels, the Magi are chasing after a UFO; but, both have come to do Christ homage. The Magi get a feast on the Roman Calendar to commemorate their visit; the shepherds get an afterthought on a feast of the Mother of God. I wonder which visit our Lord appreciated more. Wednesday I had asked the question, “Who have you been this past year, and whom do you want to be?” Some people, I suppose, are fortunate enough to be Magi: well respected, always appreciated, all the mistakes they make are somehow excused; but most of us, I think, are shepherds: schlepping along, doing the best we think we can for our Lord, grateful for what we've received, but never seeming to have much to give in return. But then I pointed out that when the Magi are done bowing and scraping and handing over their expensive presents and then leave, nothing is said; there is no recorded reaction from either the Mother of God or Her husband in today’s Gospel lesson from Matthew.  But after the shepherds leave, Saint Luke is very clear: “And Mary kept all these things, reflecting on them in her heart” (Luke 2: 19 NABRE). And I concluded Wednesday’s homily by suggesting that it is no small thing to be a reflection in the Heart of our Immaculate Mother. But after the shepherds leave, Saint Luke is very clear: “And Mary kept all these things, reflecting on them in her heart” (Luke 2: 19 NABRE). And I concluded Wednesday’s homily by suggesting that it is no small thing to be a reflection in the Heart of our Immaculate Mother.

But the one thing the Shepherds and the Magi do have in common is the fact that both of them somehow knew enough to seek out and adore a child who gave no outward sign of being anything but a very normal little boy, and therein lies an important lesson for us. I fear sometimes that we are in danger of not fully realizing how close our Lord is to our lives because God presents Himself to us under the insignificant appearance of a piece of bread, because He does not reveal Himself outwardly in His glory, because He does not impose Himself irresistibly upon us, because He slips into our lives like a shadow. How many souls are troubled by doubt simply because God does not show Himself in the way they expected? We talked about this just before New Year’s Day in conjunction with our Lord’s Circumcision: how did Simeon and Anna recognize the child before them as God? God's incarnation was total: there was nothing in His outward appearance that made this little boy stand out. He didn’t have a glowing halo over His head like a holy card. Anna’s and Simeon’s life of prayer and penance must have given them a special insight in grace to be particularly attuned to divine things, and their recognition of Jesus as God reminds us of our need to constantly be on the watch for the manifestations of Christ among us—among our friends, our families, our trials and tribulations, and all the circumstances we have every day to encounter our Lord in places where we least expect Him. And what an important reflection for us that can be as this holy season starts to wind down. So often people in confession will complain that they're in a dark place, that they don't feel their prayers are being answered, that they don't feel the presence of God in their lives; but, the example of these elderly prophets points to the fact that this kind of consolation is the result of fasting and prayer and complete abandonment to the will of God.

Getting back to the Magi and the Shepherds, two very different kinds of people, one group adoring our Lord on A&E followed by Masterpiece Mystery, the other on Spike TV followed by the Ultimate Fighter. But it doesn’t matter. Somehow they both were able to discern God in a child who looked like every other. And it is interesting to note that the Council of Trent expressly cites today’s Gospel lesson about the adoration of the Kings to teach us the cult which is due to Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. Jesus present in the tabernacle is the same Jesus the wise men found in Mary’s arms.  Perhaps we should examine ourselves to see how we adore Him when he is exposed in the monstrance or hidden in the tabernacle, with what devotion we should kneel in the moments indicated in the Holy Mass, or every time we pass by where the Blessed Sacrament is reserved, and with what care and reverence we should approach Him when receiving Holy Communion. Perhaps we should examine ourselves to see how we adore Him when he is exposed in the monstrance or hidden in the tabernacle, with what devotion we should kneel in the moments indicated in the Holy Mass, or every time we pass by where the Blessed Sacrament is reserved, and with what care and reverence we should approach Him when receiving Holy Communion.

I mentioned the significance many people over the years have chosen to see in the Magi’s gifts: gold is a symbol of royalty, reminding us that Christ is our King; frankincense was burned on the altar of the Temple as a symbol of hope, and of our desire to live lives which give off the “aroma of Christ,” as Saint Paul put it (II Cor. 2: 15); and myrrh may be the most significant one of all, as it was the oil used to anoint the bodies of the dead, reminding us of the reason God is born into the world, and how following Him will involve a life of sacrifice.

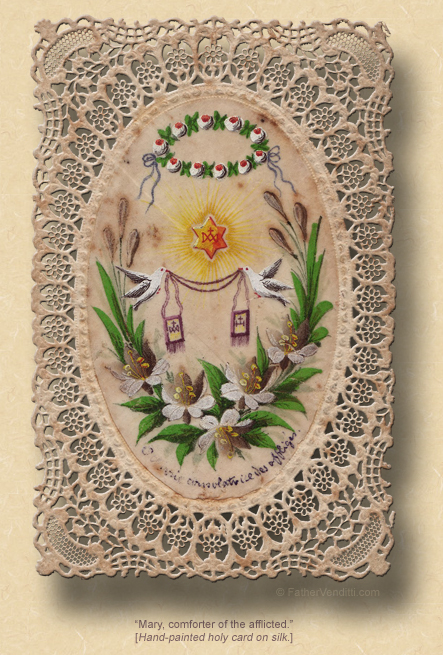

Here’s one final thought: Mare, in Latin, means “ocean” or “sea”; the familiar invocation in the Litany of Loreto is not something that someone just made up: the name “Maria” is nothing more than a shortened version of Stella Maris or “Star of the Sea,” referring to the star by which a sailor will navigate and find his way when there are no landmarks to guide him. And “Star of the Sea” is a most fitting name for the Virgin Mother of God, Who can well be compared to a star; for, just as a star beams forth its rays without being diminished in any way, so Mary gave birth to a Son without any loss of Her virginity. She is that noble Star risen from Jacob and raised by God above the great and wide sea of this passing world, and shines with virtue to enlighten us with Her own bright example. The Magi had a star to guide them, and it led them straight to the manger. But we have our own star, we who find ourselves tossed to and fro on the ocean of this valley of tears, trying desperately to navigate the murky waters of worry and worldly concerns, often finding ourselves lost and without any landmarks to guide us. Follow Mary, and She will always lead you to the manger, always lead you to Her Son.

* The Epiphany among the Traditions:

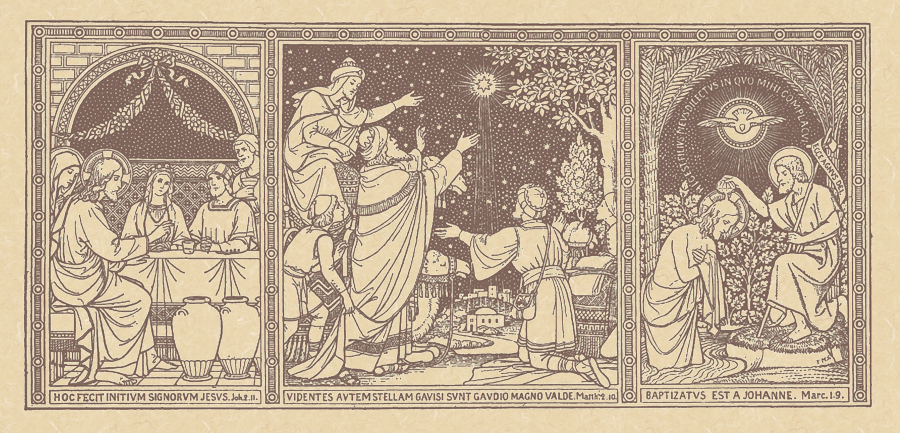

In the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, the First Class Feast of the Epiphany, always celebrated on January 6th, commemorates three events in the life of our Blessed Lord: His manifestation to the gentiles in the visit of the Magi, His manifestation as the co-eternal Son of God in His baptism by John, and His manifestation as God Incarnate in the miracle at the wedding at Cana; thus the woodcut print serving as the top image for this page, taken from an edition of the Missal of St. John XXIII, displays all three events together. While the Epiphany is not officially followed by an octave, it does have a sort of octave day, January 13th, which carries the title of the Baptism of the Lord, and appears to be a second commemoration of that event; but, the Mass and office of that day are almost identical to that of the Epiphany and, should it fall on a Sunday, it is completely displaced by the Feast of the Holy Family.

In the ordinary form of the Roman Rite, the Solemnity of the Epiphany, celebrated on January 6th on the universal calendar and on the Sunday following the Octave in the United States, commemorates only the visit of the Magi, with His baptism commemorated on the following Sunday (or, on the following Monday if there is no available Sunday), which is the Feast of the Baptism of the Lord, after which the season of Ordinary Time begins. The Gospel of the Wedding at Cana is read on January 7th should that day fall before the Epiphany; otherwise, it is not commemorated until the Second Sunday of Ordinary Time, and then only on every third year, when the lessons of the tertiary dominica are read.

In the Byzantine Rite, the Solemn Holy Day of the Theophany, always celebrated on January 6th, commemorates only the Baptism of the Lord, and thus corresponds to the feast of that name in the Roman Rite rather than to the Epiphany, with there being no specific commemoration of the visit of the Magi apart from Christmas Day. The Wedding at Cana is not commemorated in this season, but first appears in the Divine Liturgy for the Second Monday of Pascha (Easter).

|